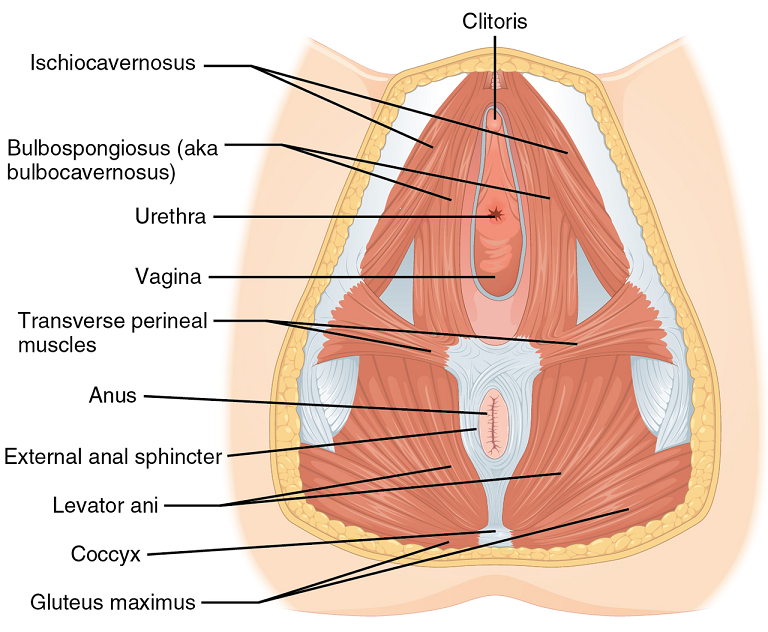

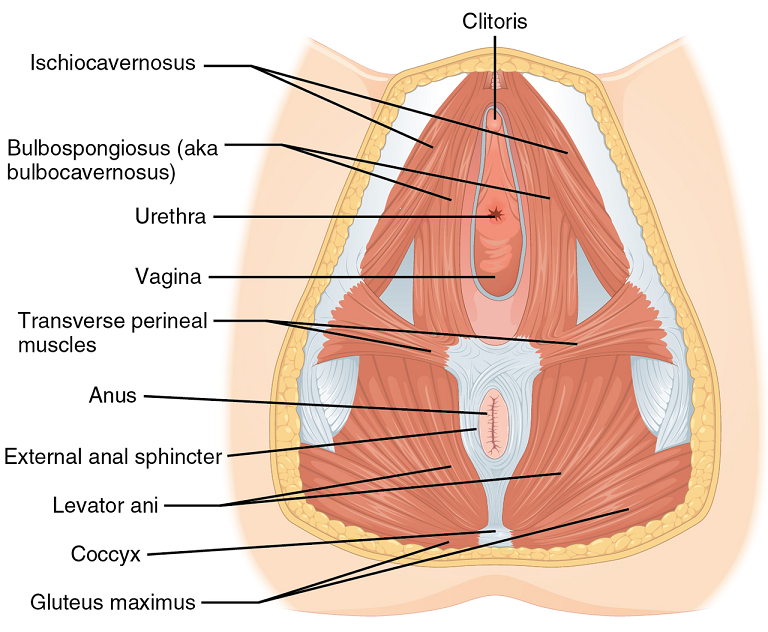

Perineal massage involves pelvic floor muscle stretching by application of an external pressure to muscle and connective tissue in the perineal region. It is performed 4 to 6 weeks before childbirth to help the soft tissue in that region to withstand stretching during labor. This helps to prevent perineum during birth by decreasing the need for an episiotomy or an instrument-assisted delivery. Lengthening of skeletal muscles is known to modify the viscoelastic properties of the muscle-tendon unit, which decreases the tension peak of the musculature and therefore, chances of injury.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Pelvic floor muscle stretching is performed via widening of the hiatus in the axial plane. Perineal massage is a simple technique has been found to be associated with a decrease in the incidence of perineal tears requiring suture or an episiotomy. It has also been reported to reduce postpartum pain.

Instrument-assisted stretching is performed with the help of an inflatable silicon balloon that can be pumped to gradually stretch the vagina and perineum. However, the evidence to support its benefit is lacking. In fact, there is some concern that pelvic floor muscle stretching may cause a decrease in muscle strength. Some have argued that such exercise neither improve or worsen pelvic function (Labrecque M, et al., Medi-dan, et al.). While a meta-analysis by Aquino, et al. concluded that perineal massage during labor significantly lowered risk of severe perineal trauma, such as third and fourth degree lacerations (Aquino, et al.).

A recent major study done by deFreitas, et al., perineal massage and instrument-assisted stretching were found to improve perineal muscle extensibility when performed in multiple sessions on primiparous women beginning at 34th week of gestation, which is very helpful in preventing child trauma in labor; however, there was no increase in muscle strength.

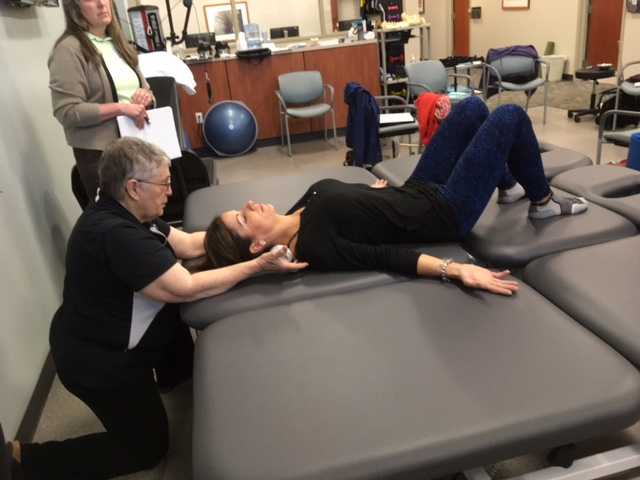

The technique of performing the manual perineal massage (as exemplified in the aforementioned study) may involve two sessions per week for a month by an OBGYN-focused physiotherapist. The patients are rested in dorsal decubitus position with the inferior limbs semi-flexed and the lower limbs and feet supported on the examination table. Coconut oil can be used for the perineal massage - which starts off with circular movements in the external area of the vulva, around the vagina and in the central tendon of the perineum, followed by the index and middle fingers inserted approximately 4 cm in the vaginal introitus for an internal massage of the lateral walls of the vagina ending toward the anus, repeated four times on each side, with the whole process lasting approximately 10 minutes.

Instrument-assisted procedure may include inserting the instrument (Epi-No) covered with a condom and lubricated with a water-based gel, inflated at the vaginal introitus so that 2 cm of the balloon is visible, making sure the patient can tolerate the stretching, and are advised to keep the pelvic floor relaxed as the instrument is slowly expelled during expiration. Physiotherapist supervision is necessary in order to maintain the correct positioning of the balloon as it lengthens the muscles. He/she will also ensure proper expulsion of the equipment during expiration.

Overall, perineal massage techniques (with or without instrumentation) are beneficial in terms of preventing trauma during labor. There are many studies that support the efficacy of these techniques in doing so (Leon-Larios, et al.). But it is also important to appreciate the limitations and use it judiciously.

Randomized trial of perineal massage during pregnancy: perineal symptoms three months after delivery. Labrecque M, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000.

Perineal massage during pregnancy: a prospective controlled trial. Mei-dan E, et al. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008.

Perineal massage during labor: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aquino CI, et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018.

Effects of perineal preparation techniques on tissue extensibility and muscle strength: a pilot study. de Freitas SS, et al. Int Urogynecol J. 2018.

Influence of a pelvic floor training programme to prevent perineal trauma: A quasi-randomised controlled trial. Leon-Larios F, et al. Midwifery. 2017.

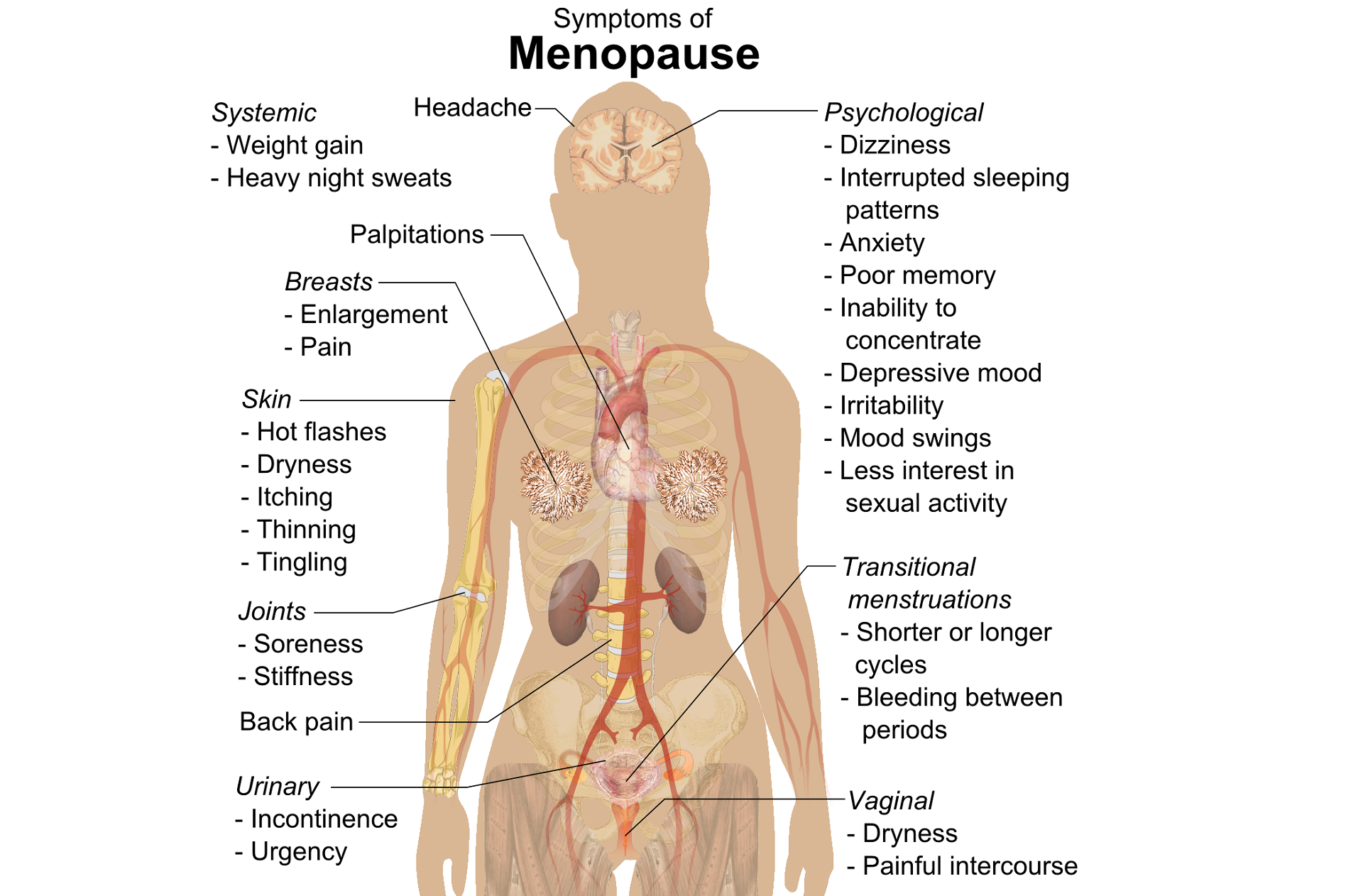

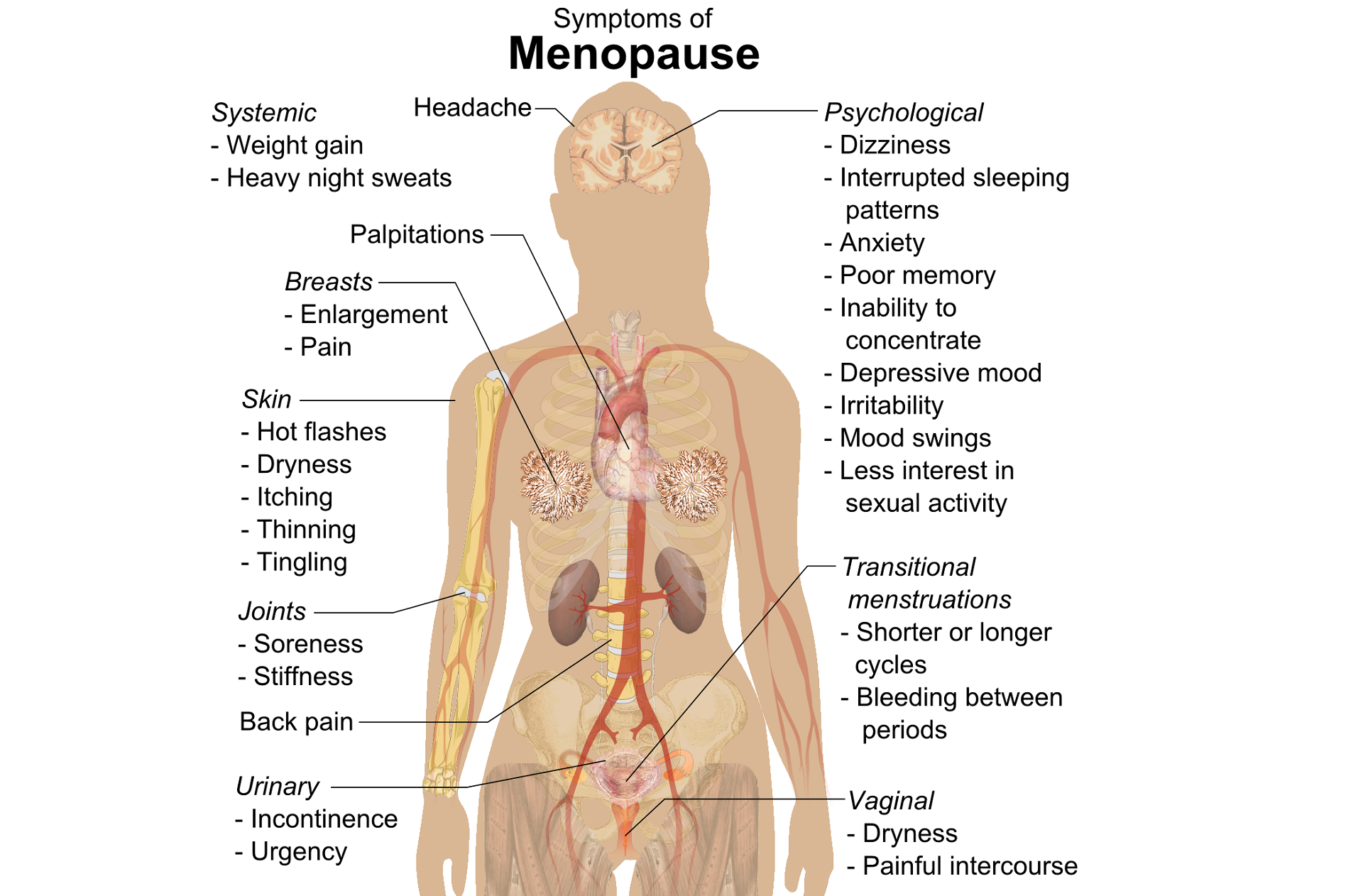

A question that often comes up in conversation around menopause is that of pelvic health – the effects on bladder, bowel or sexual health…what works, what’s safe, what’s not? Is hormone therapy better, worse or the same in terms of efficacy when compared to pelvic rehab? Do we have a role here?

An awareness of pelvic health issues that arise at menopause was explored in Oskay’s 2005 paper ‘A study on urogenital complaints of postmenopausal women aged 50 and over’ stating ‘…Urinary incontinence and sexual problems, particularly decline in sexual desire, are widespread among postmenopausal women. Frequent urinary tract infections, obesity, chronic constipation and other chronic illnesses seem to be the predictors of UI.’

Moller’s 2006 paper explored the link between LUTS (Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms) and sexual activity at midlife: the paper discussed how lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have a profound impact on women’s physical, social, and sexual well being, and confirmed that LUTS are likely to affect sexual activity. However, they also found that conversely, sexual activity may affect the occurrence of LUTS – in their study a questionnaire was sent to 4,000 unselected women aged 40–60 years, and they found that compared to women having sexual relationship, a statistically significant 3 to 6 fold higher prevalence of LUTS was observed in women with no sexual relationship. They also found that women who ceased sexual relationship an increase in the de novo occurrence of most LUTS was observed, concluding that ‘…sexual inactivity may lead to LUTS and vice versa’.

Moller’s 2006 paper explored the link between LUTS (Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms) and sexual activity at midlife: the paper discussed how lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have a profound impact on women’s physical, social, and sexual well being, and confirmed that LUTS are likely to affect sexual activity. However, they also found that conversely, sexual activity may affect the occurrence of LUTS – in their study a questionnaire was sent to 4,000 unselected women aged 40–60 years, and they found that compared to women having sexual relationship, a statistically significant 3 to 6 fold higher prevalence of LUTS was observed in women with no sexual relationship. They also found that women who ceased sexual relationship an increase in the de novo occurrence of most LUTS was observed, concluding that ‘…sexual inactivity may lead to LUTS and vice versa’.

So, who advises women going through menopause about issues such as sexual ergonomics, the use of lubricants or moisturisers, or provide a discussion about the benefits of local topical estrogen? As well as providing a skillset that includes orthopaedic assessment to rule out any musculo-skeletal influences that could be a driver for sexual dysfunction? That would be the pelvic rehab specialist clinician! Tosun et al asked the question ‘Do stages of menopause affect the outcomes of pelvic floor muscle training?’ and the answer in this and other papers was yes; with the research comparing pelvic rehab vs hormone therapy vs a combination approach of pelvic rehab and topical estrogen providing the best outcomes. Nygaard’s paper looked at the ‘Impact of menopausal status on the outcome of pelvic floor physiotherapy in women with urinary incontinence’ and concluded that : ‘…(both pre and postmenopausal women) benefit from motor learning strategies and adopt functional training to improve their urinary symptoms in similar ways, irrespective of hormonal status or HRT and BMI category’.

We must also factor in some of the other health concerns that pelvic health can impact at midlife for women – Brown et al asked the question ‘Urinary incontinence: does it increase risk for falls and fractures?’ They answered their question by concluding that ‘‘… urge incontinence was associated independently with an increased risk of falls and non-spine, nontraumatic fractures in older women. Urinary frequency, nocturia, and rushing to the bathroom to avoid urge incontinent episodes most likely increase the risk of falling, which then results in fractures. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of urge incontinence may decrease the risk of fracture.’

If you are interested in learning more about pelvic health, sexual function and bone health at Menopause, consider attending Menopause Rehabilitation and Symptom Management.

Sexual activity and lower urinary tract symptoms’ Møller LA1, Lose G. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006 Jan;17(1):18-21. Epub 2005 Jul 29.

A study on urogenital complaints of postmenopausal women aged 50 and over. Oskay UY1, Beji NK, Yalcin O. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005 Jan;84(1):72-8.

Do stages of menopause affect the outcomes of pelvic floor muscle training? Tosun ÖÇ1, Mutlu EK, Tosun G, Ergenoğlu AM, Yeniel AÖ, Malkoç M, Aşkar N, İtil İM. Menopause. 2015 Feb;22(2):175-84. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000278.

‘Impact of menopausal status on the outcome of pelvic floor physiotherapy in women with urinary incontinence.’ Nygaard CC1, Betschart C, Hafez AA, Lewis E, Chasiotis I, Doumouchtsis SK. Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Dec;24(12):2071-6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2179-7. Epub 2013 Jul 17

After completing an intake on a patient and learning that her history of constipation started about 3 years ago with insidious onset, the story wasn’t really making any sense of how or why this started. Yes, she was menopausal. Yes, she seemed to be eating fiber and drinking water. Yes, she got a bowel movement urge daily, but her bowel movements felt incomplete. Yes, she was a little older, using Estrace cream, and her mobility had slowed down, but nothing seemed to make sense in the story that was leading me to believe it was an emptying problem or a stool consistency issue. She had a bowel movement urge, she could empty, but it was incomplete.

So, after explaining about physical therapy, the muscle problems involved and what we do here, it led us to the physical examination portion. I explained that we check both the vaginal and rectal pelvic floor muscle compartments to determine rectal fullness internally, check for a rectocele, check for muscle lengthening (excursion) and shortening (contraction). She was on board and desperate to find an answer. She was eager for me to help her find an answer to her emptying problem that she had for the last 3 years.

So, after explaining about physical therapy, the muscle problems involved and what we do here, it led us to the physical examination portion. I explained that we check both the vaginal and rectal pelvic floor muscle compartments to determine rectal fullness internally, check for a rectocele, check for muscle lengthening (excursion) and shortening (contraction). She was on board and desperate to find an answer. She was eager for me to help her find an answer to her emptying problem that she had for the last 3 years.

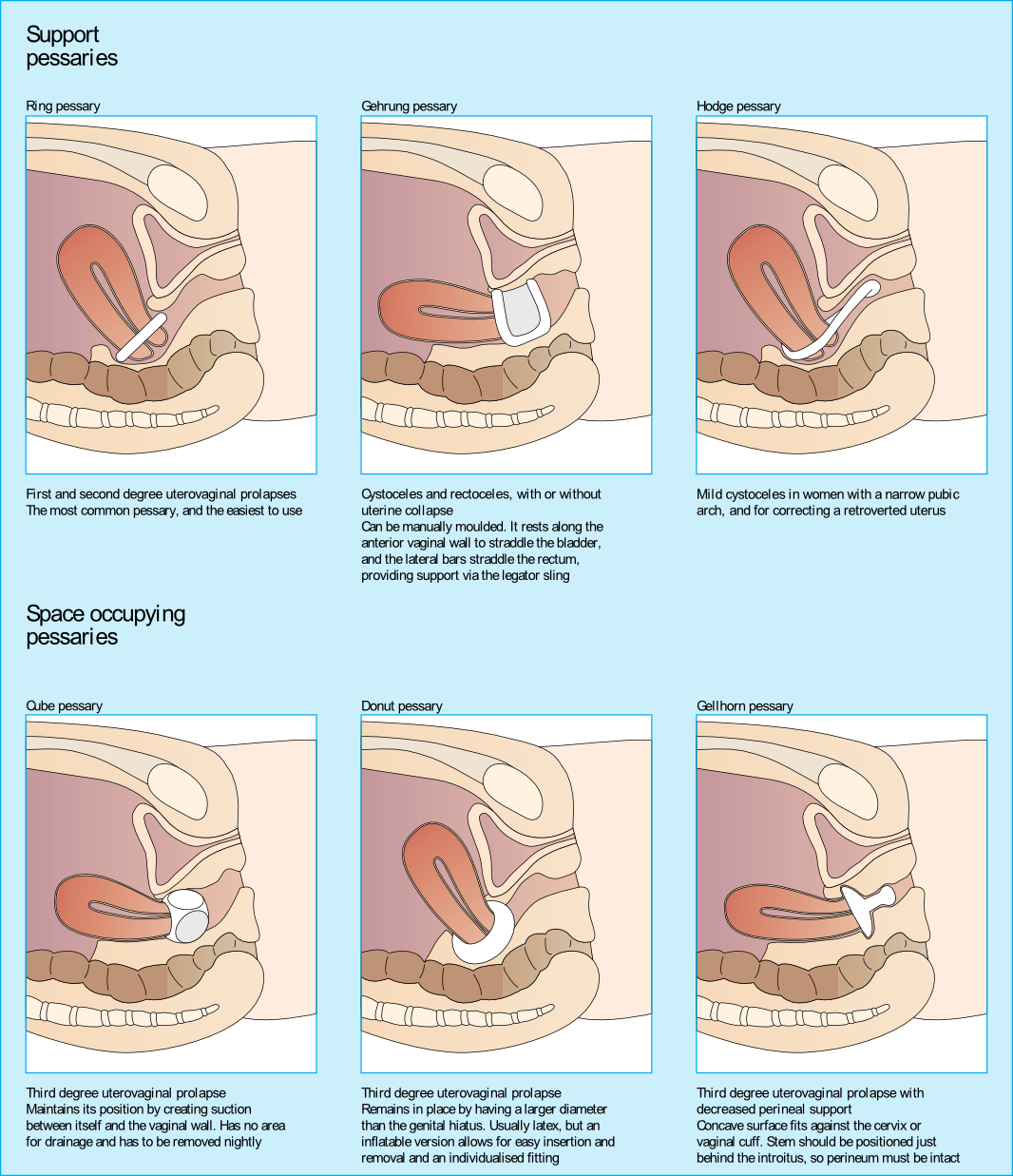

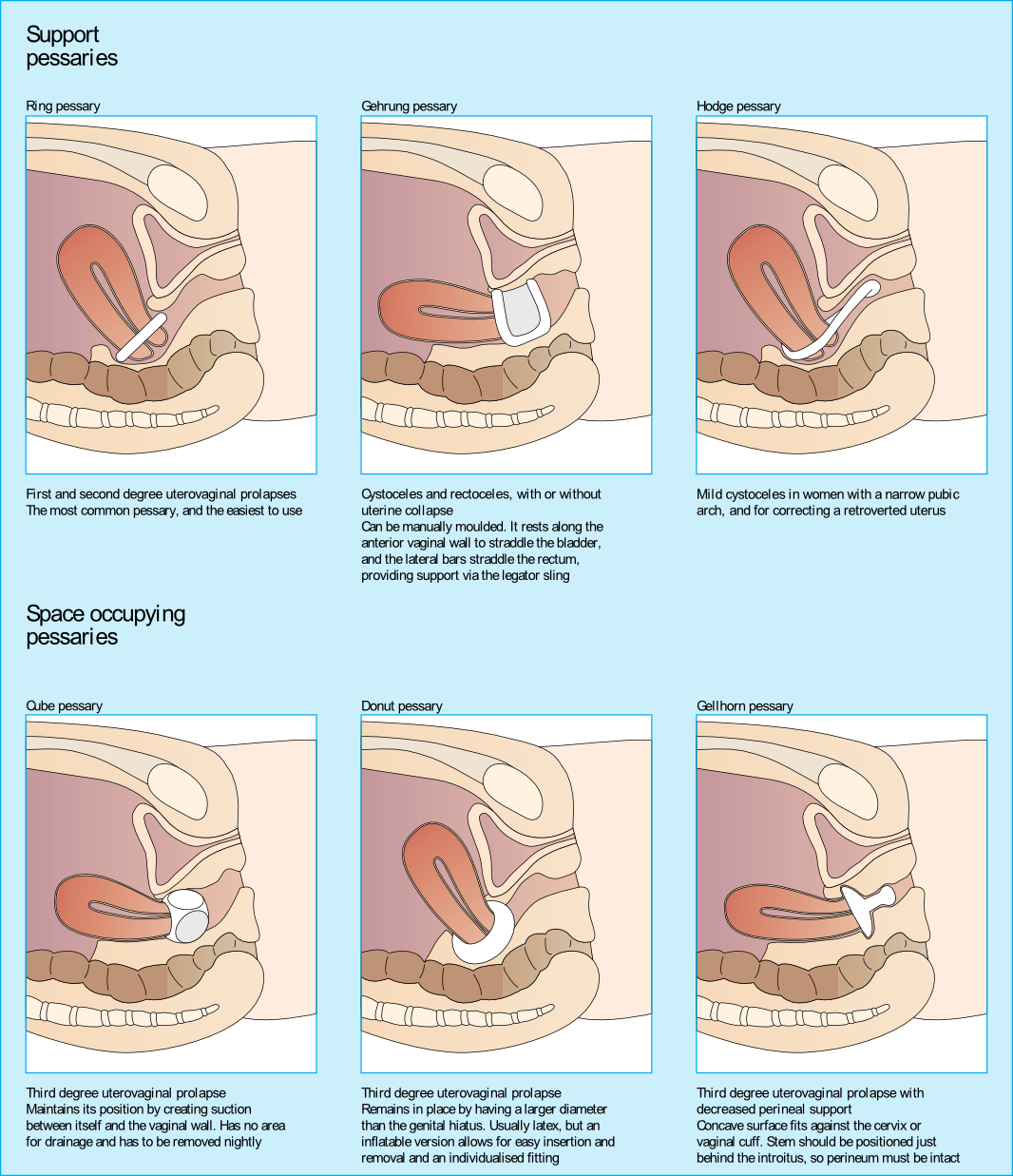

Upon entering her vaginal canal slowly, I start to move around and felt a ring of plastic. “Are you wearing a pessary?” I asked. “Pessary? Oh, yes, I forgot to tell you about that!”, she exclaimed. “How long have you been using it?” I asked. “About 3 years…” she answered.

I sent her back to the urogynecologist to get fit for another type of pessary as her muscle examination proved to be negative. Since that time, I have added the question “Do you wear a pessary?” as part of the constipation intake questions. Pessary use creates the ability for a patient to forgo or to extend their time for a surgical intervention due to pelvic organ prolapse.

Looking at the dynamics of the pessary, it may block bowel movement emptying. The recent study by Dengle, et al, published in the October 2018 in the International Urogynecological Journal confirms this anecdotal, clinical finding. The article, Defecatory Dysfunction and Other Clinical Variables Are Predictors of Pessary Discontinuation, looked at reasons for discontinuation of pessary use from April 2014 to January 2017 and did a retrospective chart review on a selected 1071 women. Incomplete defecation had the largest association with pessary discontinuation.

While there are over 20 sizes of pessaries on the market, patients will discontinue use without having a better conversation with their practitioner. From a PT perspective, when the patient comes in with bowel emptying issues, if no muscle dysfunction is found, it needs to be brought to the provider’s attention. Our role in educating the patient on the options that are available and creating this dialogue can prove to be very helpful in those suffering from pelvic organ prolapse and defecatory dysfunction.

Dengler, EG et al. "Defecatory dysfunction and other clinical variables are predictors of pessary discontinuation." Int Urogynecol J. 2018 Oct 20. doi: 10.1007/s00192-018-3777-1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30343377

Authors: Tamara Rial, PhD, CSPS, Kathleen Doyle-Elmer, PT, DPT and Rebecca Keller, PT, MSPT, PRPC

Tamara Rial, PhD, CSPS, co-founder and developer of Low Pressure Fitness will be presenting the first edition of Low Pressure Fitness and Abdominal Massage for Pelvic Floor Care Level 2 and 3 in Princeton, New Jersey in September, 2019. Rebecca Keller and Kathleen Doyle-Elmer are certified Low-Pressure Fitness specialists with training in rehabilitative ultrasound imaging. In this article, the authors discuss and explore the use of transabdominal ultrasound during Low Pressure Fitness on the abdominal and pelvic floor structures.

Real-time ultrasound imaging is a reliable and valid method to evaluate muscle structure, activity and mobility. Over the past few years, there has been increasing interest in the use of transabdominal ultrasound in the field of rehabilitation. The additional value of ultrasound imaging is that it allows for real-time analysis and visual feedback during the performance of pelvic floor and abdominal exercises (Hides et al., 1998). In the field of pelvic health, this is of notable importance when assessing proper movement of the deep abdominal and pelvic muscles during voluntary muscle actions. Transabdominal ultrasound has been found to be a safe, noninvasive, and accurate method to assess and observe muscular and fascial activity (Khorasani et al., 2012). When therapists learn how to properly use and apply ultrasound imaging, this technique can be a comprehensive tool for the clinician and a comfortable procedure for the patient. Moreover, it may be the method of choice for some patients who don’t want to have an internal pelvic examination (Van Delft, Thakar & Sultan, 2015). In this regard, a cross-sectional study found a moderate-to-strong correlation between ultrasound measurements and both digital examination and perineometry for the assessment of pelvic floor muscle actions (Volløyhaug et al., 2016).

Recently, Low Pressure Fitness has gained popularity as a pelvic floor training program aimed at reducing pressure on the pelvic structures while engaging the stabilizing muscles through postural and breathing exercises. In order to evaluate proper execution of Low-Pressure Fitness exercises as well as abdomino-pelvic muscle function during this type of training, real-time transabdominal ultrasound can be a clinically relevant tool.

Sagittal and Transverse Pelvic Floor/Urinary Bladder Assessment

The amount of movement of the bladder base on transabdominal ultrasound is considered an indicator of pelvic floor muscle mobility during pelvic floor muscle exercises (Khorasani et al., 2012). When properly executed, the Low-Pressure Fitness technique will allow the bladder to lift and the pelvic floor muscles to contract. These observed actions can be cued and progressed due to the real-time imaging biofeedback of the ultrasound. Because of the postural activation and diaphragm lift occurring during Low Pressure Fitness, the bladder fascial support system is tensioned resulting in a desirable bladder lift.

For example, we used a Pathway® Musculoskeletal Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging unit with a curvilinear transducer and Prometheus Pathway® rehabilitative ultrasound software utilizing the pre-set parameters (Abdominal Wall 7.5MHz and Bladder 5.0MHz) during a Low-Pressure Fitness basic supine posture. A standardized bladder filling protocol was used before imaging to ensure sufficient bladder filling to allow clear imaging of the base of the bladder and pelvic floor muscles.

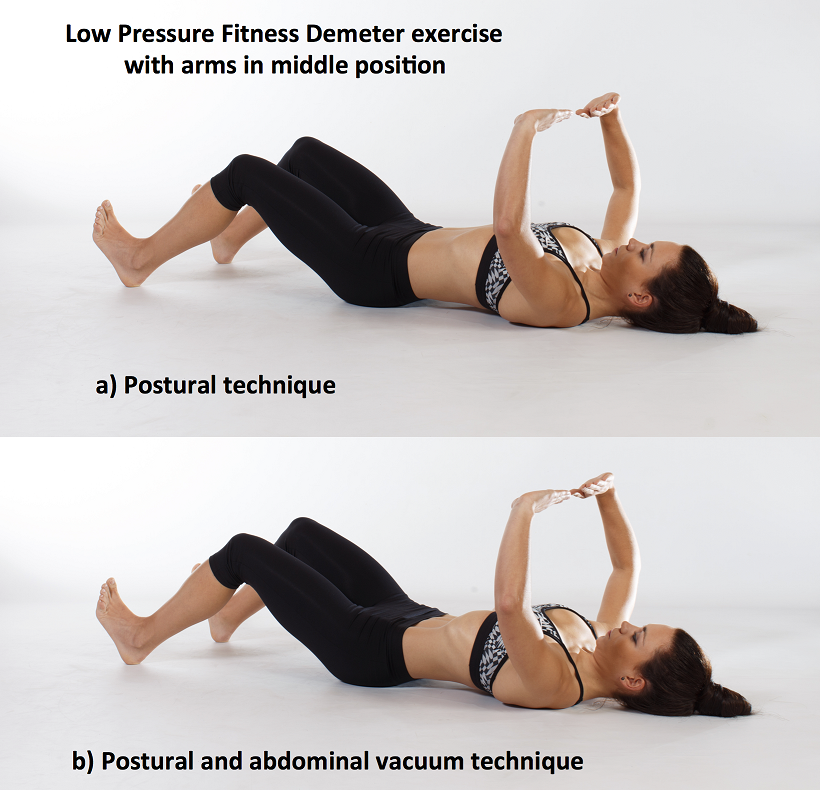

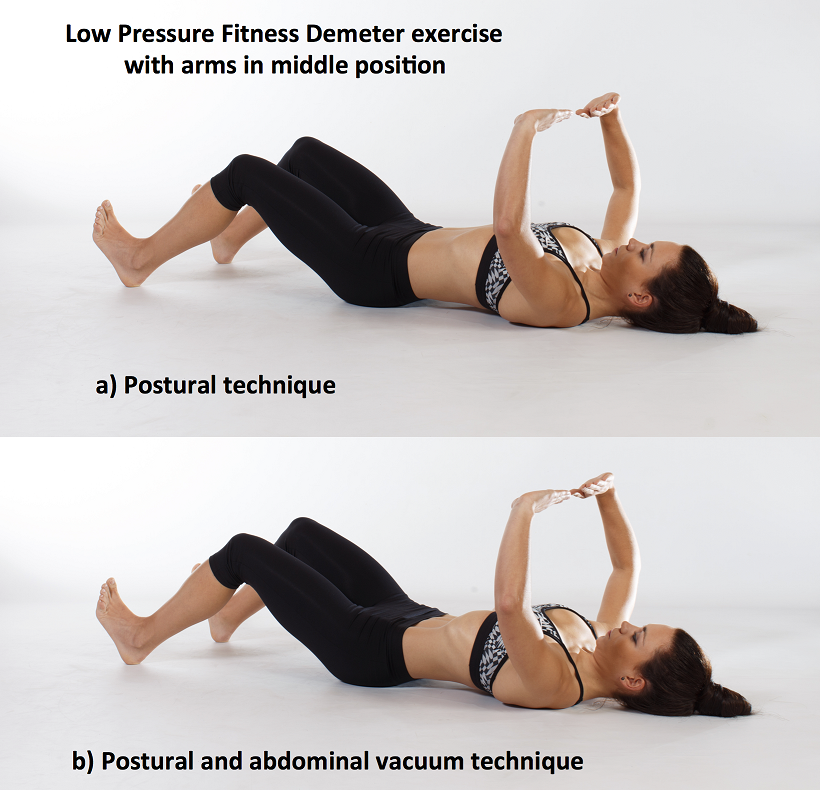

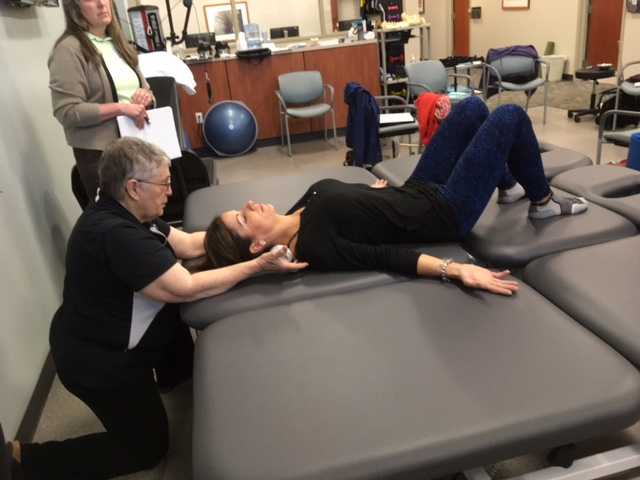

For the transverse view, radiologic standards were used, and the ultrasound transducer was placed in the transverse plane suprapubically and angled in a caudal/ posterior direction to obtain a clear image of the inferior-posterior aspect of the bladder. The participant was asked to perform the Low-Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise in the supine position with a neutral pelvis and knees flexed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Demeter exercise with postural technique and with postural and abdominal vacuum technique combined.

The following video illustrates the pelvic floor/urinary bladder during: a) resting position; b) active pelvic floor contraction; c) Low Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise and; d) Low Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise combined with a voluntary pelvic floor muscle contraction. It is noticeable a greater bladder lift and pelvic floor activation with the postural and breathing cueing added to an active pelvic floor contraction than with the pelvic floor contraction alone.

Video of the behavior of the pelvic floor muscles in a sagital and transversal view during the supine position of Low Pressure Fitness and with the combination of an active pelvic floor muscle contraction.

Lateral Abdominal Wall Assessment

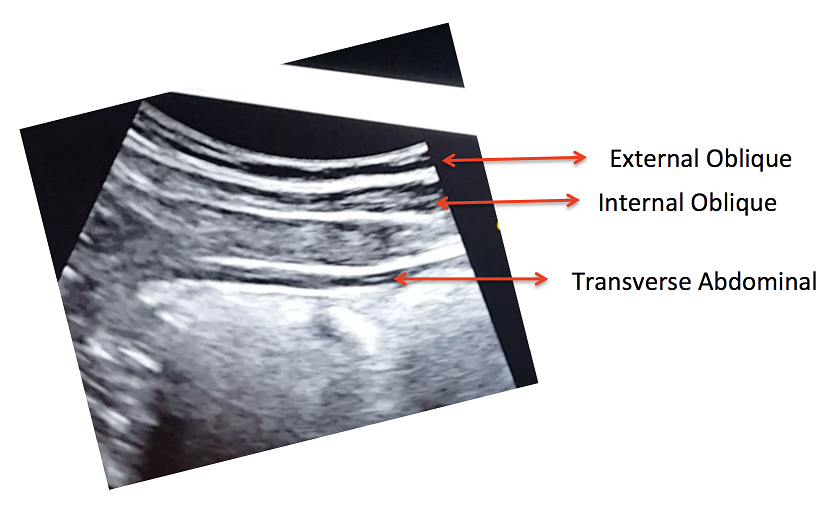

The lateral abdominal muscle ultrasound assessment allows us to observe the structural changes produced in the transversal section of the abdominal muscles in the midpoint between the anterior iliac crest and the costal angle. At low levels of contraction, the extent of transverse abdominis thickening measured using ultrasound is reported to be a valid method of assessment compared with either fine wire electromyographic measures of transverse activity (McMeeken et al., 2004). It is well established in the scientific literature that the lateral abdominal muscles provide stability to the trunk in different functional activities. Therefore, the assessment of the size, thickness and sliding of the abdominal wall is important for patients who present with lumbo-pelvic and/or pelvic floor dysfunctions. In this regard, patients with low back pain show different abdominal wall muscle activation patterns (i.e. less slide of the abdominal fascia and muscle thickness) than those without low back pain (Gildea et al., 2014; Unsgaard-Tondel et al., 2012).

Figure 2 shows the three muscle layers of the lateral wall in the resting position. The superficial layer corresponds to the external oblique, the middle layer to the internal oblique and the deep layer to the transverse abdominal muscle.

Figure 2. View of the right lateral abdominal wall at rest.

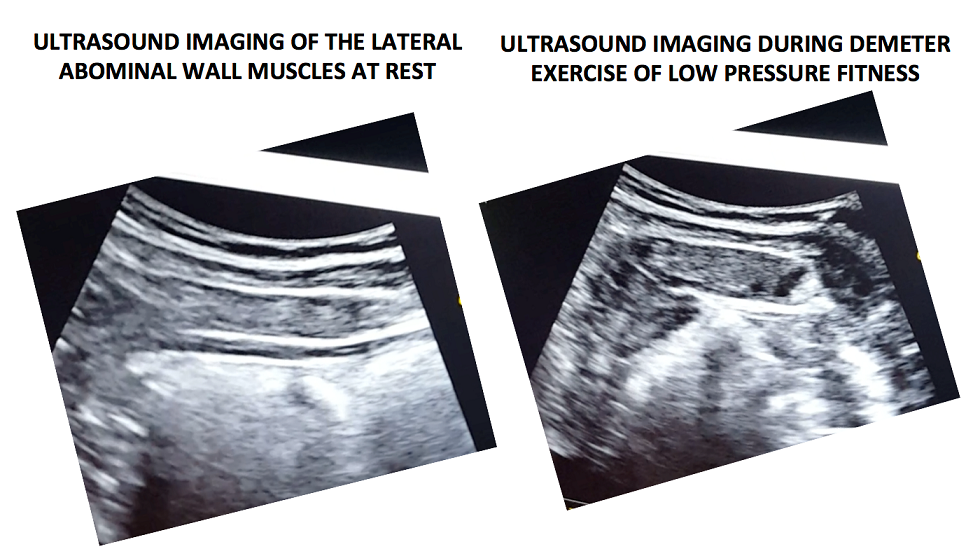

A key breathing component of the Low-Pressure Fitness program is the abdominal vacuum which manipulates intra-abdominal, intra-thoracic and intra-pelvic pressures during the breath-holding phase. Another key aspect of Low-Pressure Fitness is the shoulder girdle activation, spine elongation and ankle-dorsiflexion (Rial & Pinsach, 2017). Of note, previous studies have demonstrated greater transverse abdominis activation when performing ankle dorsi-flexion (Chon et al., 2010). We used transabdominal ultrasound to assess the lateral abdominal wall response during ankle dorsiflexion, shoulder girdle activation and the abdominal vacuum during Low Pressure Fitness.

In the following video, a voluntary (active) abdominal contraction is performed in order to distinguish this action from the involuntary abdominal contractions during Low Pressure Fitness. Afterwards, the postural technique of ankle dorsiflexion and shoulder girdle activation are performed in the Demeter exercise with arms in middle position (Figure 1). Lastly, an abdominal vacuum maneuver is added to the postural technique. If the exercises are properly executed, the progressive sliding and thickness of the abdominal muscles throughout exercise sequence should be observable (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Ultrasound imaging at rest and during the complete LPF technique.

Video of a voluntary (active) abdominal contraction or draw-in maneuver is performed in order to distinguish this action from the involuntary abdominal contractions that occur during Low Pressure Fitness in a supine position

Muscle thickness of the transverse and internal oblique as well as a noticeable slide of the anterior abdominal fascia are observable during the Demeter exercise of Low-Pressure Fitness. This exercise pattern reflects an abdominal draw-in maneuver and a “corseting effect”. In this regard, notice the lateral pull or displacement of the edge of the anterior fascial insertion of the transverse the internal oblique muscle.

Navarro et al., (2017) used transabdominal ultrasound to assess the muscular responses of the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles in a group of women who underwent pelvic physiotherapy over two months. They found a significant increase in the transversal section of the transverse abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles when compared to resting in the supine position. Similar to the position assessed by Navarro et al. (2017), we also assessed the pelvic floor and abdominal muscle responses during a Low-Pressure Fitness supine exercise.

Transabdominal ultrasound can provide a noninvasive and informative visual biofeedback when training patients with Low Pressure Fitness. This ultrasound imaging can be a valuable tool to both the client and the clinician to objectify progress, assist with validating correct Low-Pressure Fitness form with positioning and vacuum/hypopressive maneuver as well as a motivational technique for the client. As demonstrated during our rehabilitative ultrasound imaging, observable bladder lift, pelvic floor activation and desirable lateral abdominal muscular corseting (slide and thicking) occurs during Low Pressure Fitness postural exercises and breathing. Since Low Pressure Fitness is a progressive exercise program, qualified instruction, technique driven progression and understanding pelvic floor health are needed to optimize patient outcomes.

Chon SC, Chang KY, You JS. Effect of the abdominal draw-in manoeuvre in combination with ankle dorsiflexion in strengthening the transverse abdominal muscle in healthy young adults: a preliminary, randomised, controlled study. Physiotherapy 96: 130-6, 2017.

Gildea JE, Hides JA, Hodges PW. Morphology of the abdominal muscles in ballet dancers with and without low back pain: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Sci Med Sport. 17(5): 452-6, 2014.

Khorasani B, Arab AM, Sedighi Gilani MA, Samadi V, Assadi H. Transabdominal ultrasound measurement of pelvic floor muscle mobility in men with and without chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology, 80: 673-7, 2012.

McMeeken JM, Beith ID, Newham DJ, Milligan P, Critchley DJ. The relationship between EMG and change in thickness of transversus abdominis. Clin Biomech 19: 337–342, 2004.

Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Use of real-time ultrasound imaging for feedback in rehabilitation. Man Ther. 3:125-131,1998.

Navarro B, Torres M, Arranz B, Sanchez O. Muscle response during a hypopressive exercise after pelvic floor physiotherapy: Assessment with transabdominal ultrasound. Fisioterapia 39: 187-94, 2017.

Rial T, Pinsach P. Practical Manual Low Pressure Fitness Level 1. International Hypopressive & Physical Therapy Institute, Vigo, 2017.

Unsgaard-Tøndel M, Lund Nilsen TI, Magnussen J, Vasseljen O. Is activation of transversus abdominis and obliquus internus abdominis associated with long-term changes in chronic low back pain? A prospective study with 1-year follow-up. Br J Sports Med, 46(10): 729-34, 2012.

Van Delft K, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Pelvic floor muscle contractility: digital assessment vs transperineal ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 45: 217-22, 2015. Volløyhaug I, Mørkved S, Salvesen Ø, Salvesen KÅ. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle contraction with palpation, perineometry and transperineal ultrasound: a cross-sectional study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 47: 768-73, 2016.

The following is part three in a series documenting Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT's journey treating a 72 year old patient who has been living with multiple sclerosis (MS) since age 18. Catch up with Part One and Part Two of the patient case study on the Pelvic Rehab Report. Dr. Gulbrandson is a certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist and instructor of the Meeks Method, and she helps teach The Meeks Method for Osteoporosis course.

On Maryanne’s third visit, after reviewing her home exercises I told her that today our focus was on alignment. “In dealing with osteoporosis we want the forces that act upon our bodies to line up as optimally as possible. We have gravity providing a downward force from above and we have ground reaction forces coming up from below. Remember back to your first visit when we did the Foot Press in sitting and talked about Newton’s 3rd Law? For every action there’s an opposite and equal reaction and, how by pressing your feet down it helped you to sit straighter and gave more support to your back?” She nodded in agreement.

On Maryanne’s third visit, after reviewing her home exercises I told her that today our focus was on alignment. “In dealing with osteoporosis we want the forces that act upon our bodies to line up as optimally as possible. We have gravity providing a downward force from above and we have ground reaction forces coming up from below. Remember back to your first visit when we did the Foot Press in sitting and talked about Newton’s 3rd Law? For every action there’s an opposite and equal reaction and, how by pressing your feet down it helped you to sit straighter and gave more support to your back?” She nodded in agreement.

“Well, there’s another important component to that- one that we call optimal alignment. When we sit or stand in a flexed posture, those two opposing forces do not line up well and can put undue stress and pressure on our body, particularly the vertebral bodies.” I showed her the spine again with an increased flexion (hyper-kyphosis) in the thoracic area. “It’s normal to have a kyphosis in the thoracic spine. What we don’t want is a hyper-kyphosis. We often see the apex of the increased curve around T-7, 8, 9 levels near the bra line. We also call it the “slouch line” because from the front, that’s where we slouch in sitting. A thoracic hyper-kyphosis can lead to hyper-lordosis in the lumbar spine as the body tries to counteract the flexion forces above with extension or arching in the low back. We know that Wolff’s Law states that bone in a healthy person will adapt to the loads under which it is placed.1 But we want those loads to be optimally transmitted; otherwise the adaptation can be problematic.”

With Maryanne sitting in a Perch Posture position on the side of the low mat table, I placed a 4 foot dowel rod alongside her back, touching her sacrum and apex of her thoracic curve. I instructed her to bring her occiput back toward the dowel without extending her neck. I wanted her to do more of a cervical retraction move. She was a good 3+ inches away. Previously I had measured her using the WOD (Wall to Occiput Distance).2 This helps patients understand when they are forward flexed in the upper thoracic and cervical area and becomes an exercise as well. Since Maryanne was not safe in a standing position, we used an armless chair against the wall. I turned it sideways so the side of the chair was snugged up to the wall and transferred her to the chair, sitting so that her sacrum was flush against the wall. “Bring your upper back against the wall without allowing your low back to arch forward”, I told her as I placed a folded towel behind her head. “Now you’re going to press the back of your head into the towel, just as you do when lying down in the Re-alignment routine. Before you perform the Head Press, inhale to prepare, start your exhale, then do the head press. Hold for 3 -5 seconds as you continue to exhale, then relax as you inhale. Do 3-5 reps.”

The Head Press in standing, (or in Maryanne’s case, sitting) is a convenient way to not only strengthen the back muscles isometrically, but also increase awareness of body in space and relationship of head to trunk positioning. For any individual who has developed a forward head position over a period of years, there is a loss of the proprioceptive feedback necessary to know when we’re not in alignment, even if we have the ROM to achieve it. And often a lack of strength and especially muscle endurance to maintain that optimally aligned position is problematic. Using the wall several times a day can assist in building strength and awareness. In Maryanne’s case we needed a folded towel behind her occiput to give her something to press into and prevented her from going into increased cervical extension.

“I still want you to do the Head Press in supine as part of the Re-alignment routine everyday”, I told her. “But also practice it in sitting against a wall, making sure your sacrum is right up against it. Do this several times a day for several minutes, holding 3-5 seconds each. And be sure to use your breath to maintain neutral alignment of your lumbar spine.”

And with that, our work for the day was done.

1. Wolff's Law and bone's structural adaptations to mechanical usage: an ... https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8060014

2. Concurrent Validity of Occiput-Wall Distance to Measure Kyphosis in Communities. Journal of Clinical Trials. May 18, 2012 Sawitree Wongsa1,4, Pipatana Amatachaya2,4, Jeamjit Saengsuwan3,4 and Sugalya Amatachaya1,4*

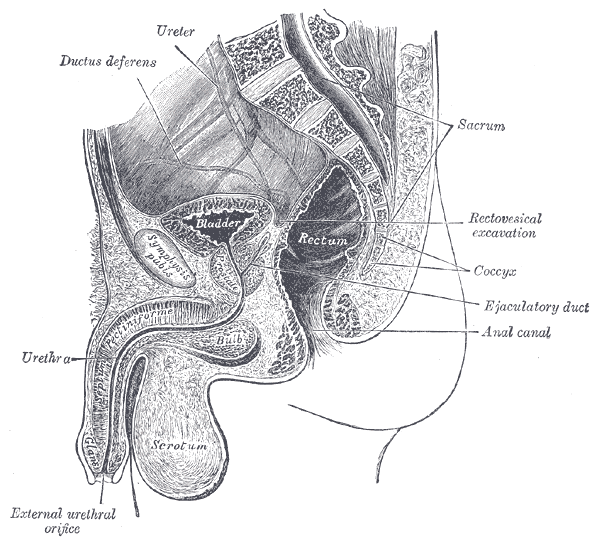

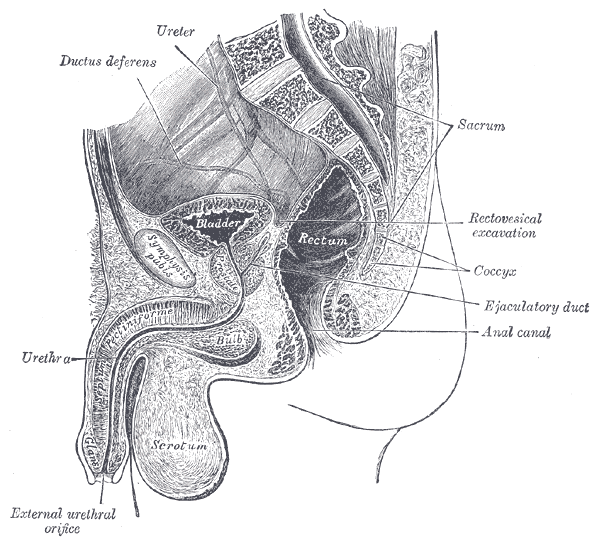

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a debilitation complication of radical prostatectomy, which is a treatment for prostate cancer. ED is caused by a variety of causes, diabetic vasculopathy, smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, psychological issues, peripheral vascular disease and medication; we will focus on post-prostatectomy ED and the role of penile rehabilitation in its management.

Post-prostatectomy-related Erectile dysfunction

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Research on penile hemodynamics in these patients have shown that venous leakage is also implicated in its pathophysiology. An injury to the neurovascular bundles likely leads to smooth muscle cell death, which then leads to irreversible veno-occlusive disease.

There is a potential role of hypoxia in stimulating growth factors (TGF-beta) that stimulate collagen synthesis in cavernosal smooth muscle. Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) was found to suppress the effect of TGF-β1 on collagen synthesis.

Role of Penile Rehabilitation

The goal of Penile Rehabilitation is to limit and reverse ED in post-prostatectomy patients. The idea is to minimize fibrotic changes during the period of “penile quiescence” after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Several approaches have been tried, including PGE1 injection, vacuum devices, and phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors.

Mulhall and coworkers followed 132 patients through an 18-month period after they were placed in “rehabilitation” or “no rehabilitation” groups after radical prostatectomy, and 52% of those undergoing rehabilitation (sildenafil + alprostadil) reported spontaneous functional erections, compared with 19% of the men in the no-rehabilitation group 2.

Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1)

Alprostadil is a vasodilatory prostaglandin E1 that can be injected into the penis or placement in the urethra in order to treat ED. Montorsi, et al. studied the use of intracorporeal injections of alprostadil starting at 1 month after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and reported a higher rate of spontaneous erections after 6 months compared with no treatment 3. Gontero, et al. investigated alprostadil injections at various time points after non–nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and found that 70% of patients receiving injections within the first 3 months were able to achieve erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 40% of patients receiving injections after the first 3 months 4.

Vacuum constriction device (VCD)

VCD is an external pump that is used to get and maintain an erection. Raina, et al evaluated the daily use of a VCD beginning within two months after radical prostatectomy, and reported that after 9 months of treatment, 17% of patients using the device had return of natural erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 11% of patients in the nontreatment group 4.

PDE-5 Inhibitors

PDE-5 inhibitors (such as Sildenafil) are the first-line treatment for ED of many etiologies. Several studies have shown that the use of PDE-5 inhibitors might lead to an overall improvement in endothelial cell function in the corpus cavernosum. Chronic use of oral PDE-5 inhibitors suggest a beneficial effect on endothelial cell function. Desouza, et al. concluded that daily sildenafil improves overall vascular endothelial cell function. However, Zagaja, et al. found that men taking oral sildenafil within the first 9 months of a nerve-sparing procedure did not have any erectogenic response 4.

Overall, accumulating scientific literature is suggesting that penile rehabilitation therapies have a positive impact on the sexual function outcome in post-prostatectomy patients. It must be noted that these methods do not cure ED and should be used with caution.

1Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701-1705.

2Mulhall J, Land S, Parker M, et al. The use of an erectogenic pharmacotherapy regimen following radical prostatectomy improves recovery of spontaneous erectile function. J Sex Med. 2005; 2:532-540.

3Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Strambi LF, et al. Recovery of spontaneous erectile function after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy with and without early intracavernous injections of alprostadil: results of a prospective, randomised trial. J Urol. 1997;158:1408-1410.

4Gontero P, Fontana F, Bagnasacco A, et al. Is there an optimal time for intracavernous prostaglandin E1 rehabilitation following non- nerve sparing radical prostatectomy? Results from a hemodynamic prospective study. J Urol. 2003;169:2166-2169.

Earlier diagnosis is clearly a huge need for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. Many patients suffer with their symptoms for years before even hearing the words “pelvic floor,” or realizing that a pelvic floor physical therapist may be able to help. For interstitial cystitis, one large survey article found fewer than 10% of patients with the condition had been correctly diagnosed with IC, even after years of symptoms and visits with multiple doctors.

Even after being diagnosed, patients still don’t learn about how the pelvic floor can be causing or exacerbating their symptoms. In one study of our interstitial cystitis patients, 46% learned about the importance of the pelvic floor on their own and sought out treatment independently, while nearly half felt they were referred by their physician to physical therapy far too late, as a ‘last resort.’ This is despite the fact that many of these patients had seen five or more physicians and physical therapy is considered the most proven treatment for IC by the American Urological Association.

Physicians, orthopedic physical therapists, other practitioners, and patients themselves need a simple, proven way to identify pelvic floor dysfunction to help patients find pelvic floor physical therapy earlier in their medical journey.

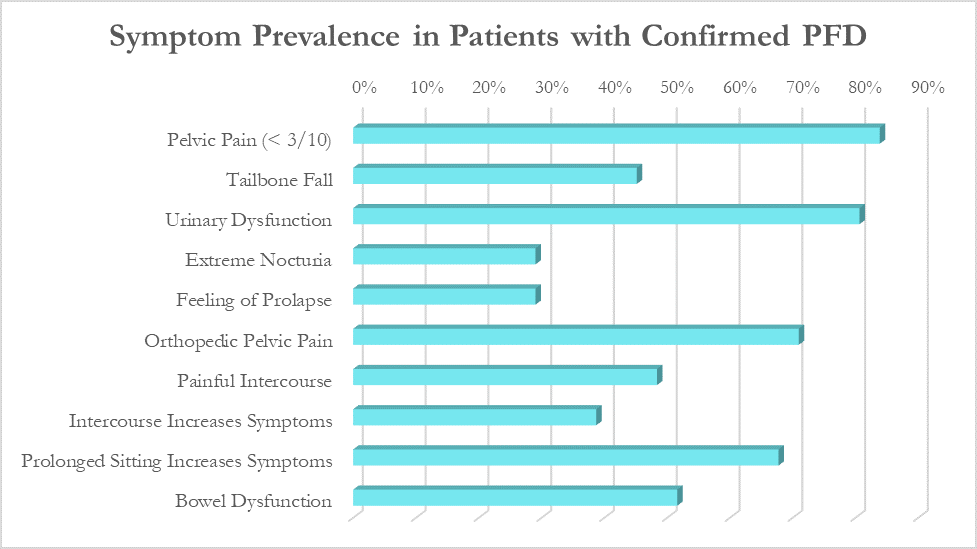

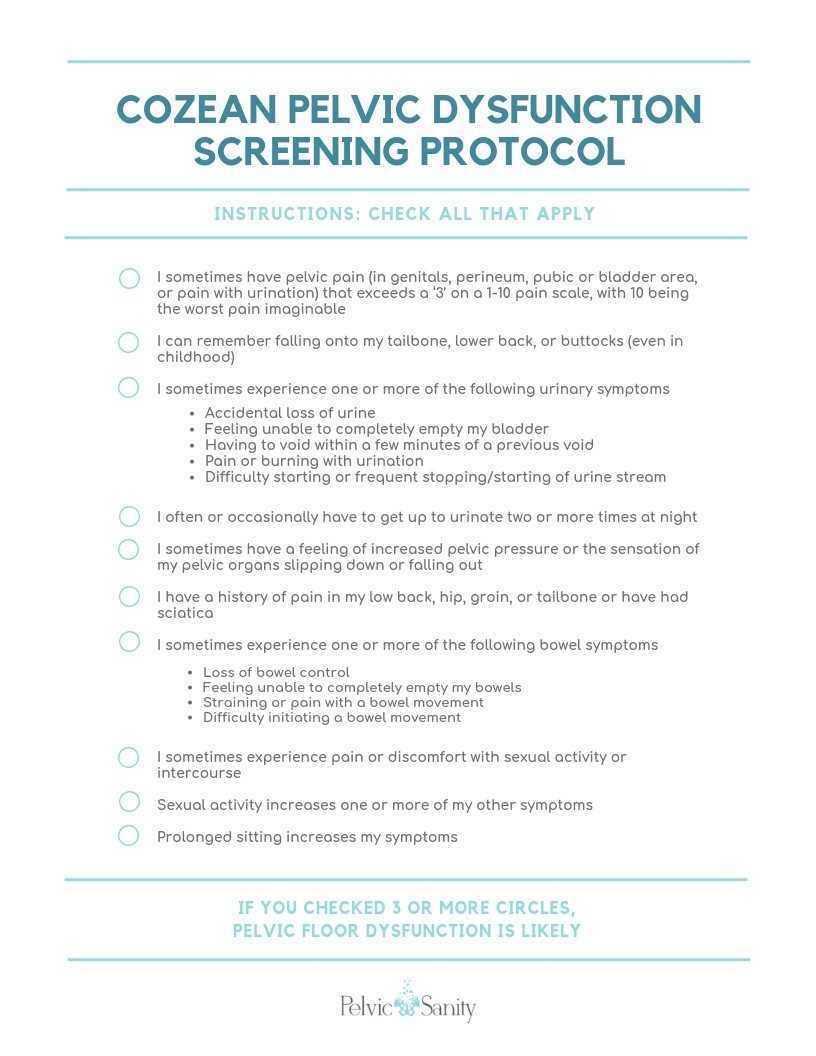

In a large survey of our patients with confirmed pelvic floor dysfunction, we examined what symptoms and medical history was most closely correlated with pelvic floor dysfunction. Any screening questionnaire would ideally be able to identify a wide variety of pelvic floor dysfunction, including patients with chronic pelvic pain, pelvic organ prolapse, orthopedic pain with a pelvic floor component (low back, hip, groin), urinary urgency/frequency, and/or bowel dysfunction.

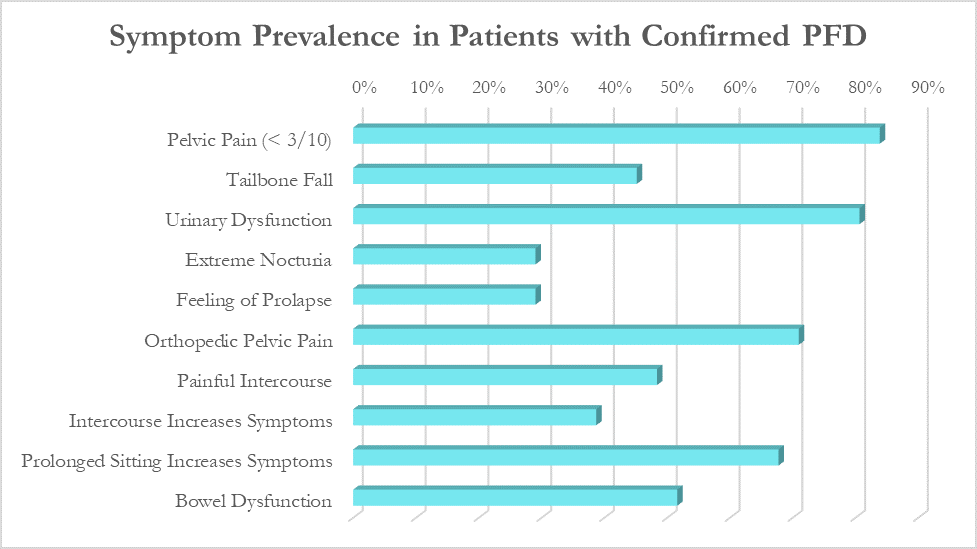

While these patients all had different medical diagnoses, many symptoms were common across the patient population. The most common were pelvic pain (84%), urinary urgency, frequency, or incontinence (81%), orthopedic pelvic pain (71%) and symptoms that worsen with prolonged sitting (68%).

Based on the survey results, we created the Cozean Pelvic Dysfunction Screening Protocol to screen for pelvic floor dysfunction and published the results in the International Pelvic Pain Society (2017). The goal was to correctly identify more than 80% of the patients with pelvic floor dysfunction (sensitivity). For ease of use by both practitioners and patients, the questions were phrased so they could be answered with a simple ‘yes/no’ (as a check box). If patients answers ‘yes’ to 3 or more of the questions, pelvic floor dysfunction is highly likely.

Document available for download at https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/d1026c_42a0fda8e5644930950d754619586614.pdf

Document available for download at https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/d1026c_42a0fda8e5644930950d754619586614.pdf

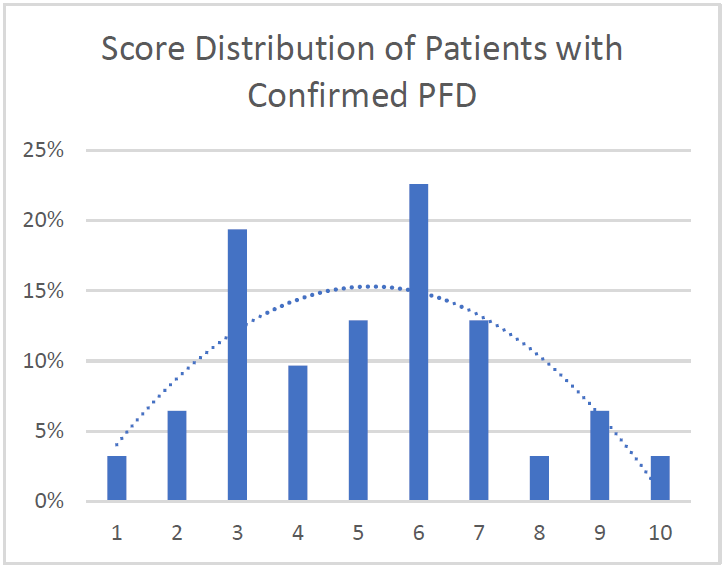

Testing the Model

In a model like this, we would expect a normal (bell-shaped) distribution curve of answers from patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. Some patients will score on the high end, others on the low, and the majority would be clustered in the middle. This is what we observe with use of the questionnaire, as seen by the trendline in the blow graph. Most patients with confirmed pelvic floor dysfunction cluster in scores between 3 and 7, with a few scoring at 8 or higher. Less than one out of ten patients with pelvic floor dysfunction score below a 2 on the questionnaire and would not be captured by this measure.

Specificity: 91%. More than 90% of patients with confirmed pelvic floor dysfunction were correctly identified by this screening protocol. Additional testing is required on a general population without PFD to determine the specificity of the questionnaire.

Average: 5.2. Of patients with confirmed PFD, the average score according to this screening protocol was 5.2 with a median score of 5 and a mode of 6. This is in line with what would be expected with a normal distribution curve.

We hope this 10-question survey is able to help patients with pelvic floor dysfunction be diagnosed earlier - whether by their physician, other physical therapists, or themselves – and seek pelvic floor physical therapy earlier in their medical journey. Please feel free to use the printable version of this protocol with your patients or in working with local practitioners.

Nicole Cozean will be teaching the course Interstitial Cystitis: Holistic Evaluation and Treatment in Princeton, NJ from April 6-7, 2019.

Nicole Cozean is the founder of PelvicSanity physical therapy, in Orange County, California. Nicole was named the 2017 PT of the Year, is the first physical therapist to serve on the ICA Board of Directors, and is the award-winning and best-selling book The Interstitial Cystitis Solution (2016). She is an adjunct professor at her alma mater, Chapman University and teaches continuing education courses through the prestigious Herman & Wallace Institute.

Nicole Cozean is the founder of PelvicSanity physical therapy, in Orange County, California. Nicole was named the 2017 PT of the Year, is the first physical therapist to serve on the ICA Board of Directors, and is the award-winning and best-selling book The Interstitial Cystitis Solution (2016). She is an adjunct professor at her alma mater, Chapman University and teaches continuing education courses through the prestigious Herman & Wallace Institute.

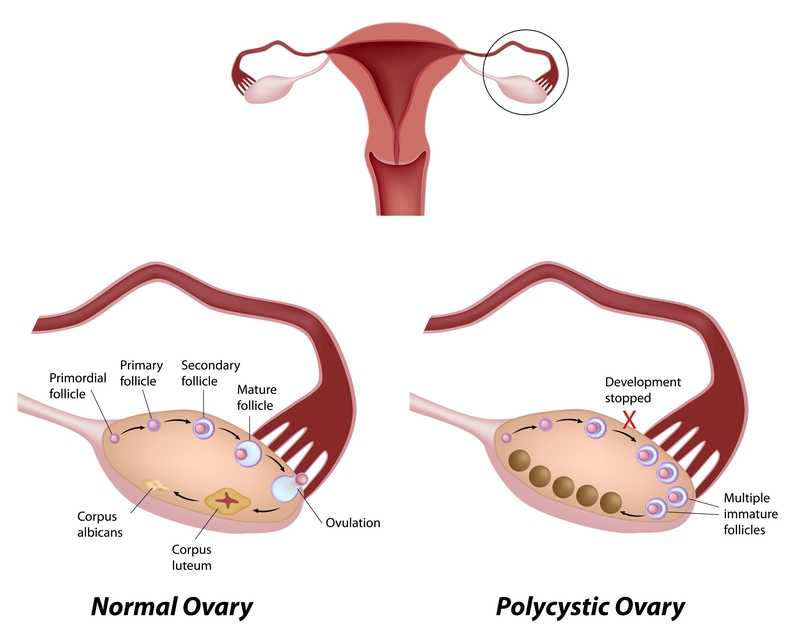

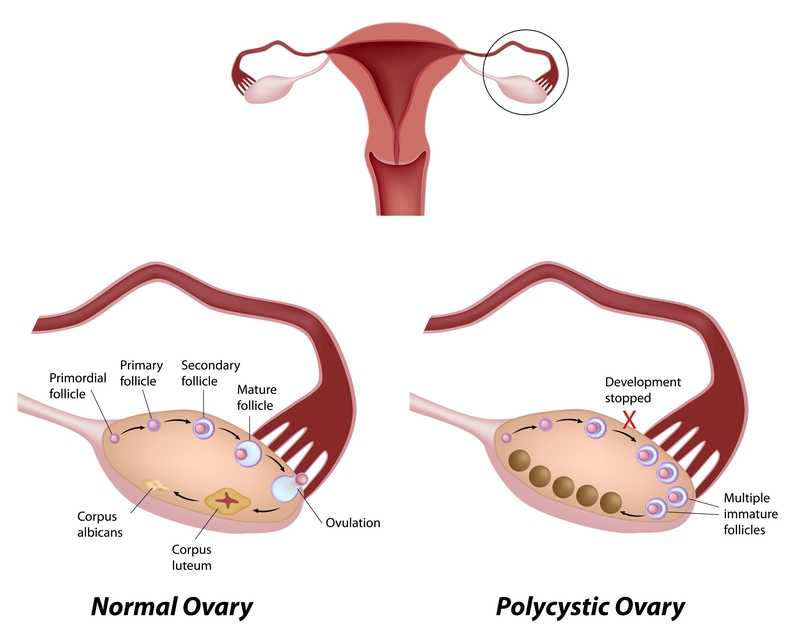

Few patients discuss polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in orthopedic manual therapy, but one lady left a lasting impression. She was adopted and did not know her family’s medical history or her genetics. At 18, she had a baby as a result of rape. At 34, she was married and diagnosed with POCS. She struggled with infertility, anxiety, obesity, and hypertension. Although I saw her for cervicalgia, the exercise aspect of her therapy had potential to impact her overall well-being and possibly improve her PCOS symptoms.

Pericleous & Stephanides (2018) reviewed 10 studies that considered the effects of resistance training on PCOS symptoms. Some of these symptoms include the absence of or a significant decrease in ovulation and menstruation, which can lead to infertility; obesity, which in turn can affect cardiovascular health and increase the risk of diabetes, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome; and, mental health problems. Research has shown resistance training benefits include lowering body fat, improving insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, and increasing insulin sensitivity in type II diabetes. Although it has been documented that obesity and insulin resistance can exacerbate PCOS symptoms, resistance training is not a common recommendation in healthcare settings for patients with PCOS . Studies have shown diet and exercise are essential to improve cardiac and respiratory health and body makeup in patients with PCOS, as the combination improves the Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), ovulation, testosterone levels, and weight loss. One systematic review found that weight loss can improve PCOS symptoms without consideration of diet; however, most other studies find intake of various macronutrients (protein, fat, carbohydrates) may lead to different results, and the effects of resistance training can only be optimized with appropriate dietary changes. These authors concluded caloric consumption and macronutrient habits must be considered in conjunction with resistance training to determine the greatest impact on improving PCOS symptoms.

Pericleous & Stephanides (2018) reviewed 10 studies that considered the effects of resistance training on PCOS symptoms. Some of these symptoms include the absence of or a significant decrease in ovulation and menstruation, which can lead to infertility; obesity, which in turn can affect cardiovascular health and increase the risk of diabetes, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome; and, mental health problems. Research has shown resistance training benefits include lowering body fat, improving insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, and increasing insulin sensitivity in type II diabetes. Although it has been documented that obesity and insulin resistance can exacerbate PCOS symptoms, resistance training is not a common recommendation in healthcare settings for patients with PCOS . Studies have shown diet and exercise are essential to improve cardiac and respiratory health and body makeup in patients with PCOS, as the combination improves the Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), ovulation, testosterone levels, and weight loss. One systematic review found that weight loss can improve PCOS symptoms without consideration of diet; however, most other studies find intake of various macronutrients (protein, fat, carbohydrates) may lead to different results, and the effects of resistance training can only be optimized with appropriate dietary changes. These authors concluded caloric consumption and macronutrient habits must be considered in conjunction with resistance training to determine the greatest impact on improving PCOS symptoms.

Benham et al., (2018) also performed a recent systematic review to assess the role exercise can have on PCOS. Fourteen trials involving 617 females of reproductive age with PCOS evaluated the effect of exercise training on reproductive outcomes. The data published did not allow the authors to quantitatively assess the impact of exercise of reproductive in PCOS patients; however, their semi-quantitative analysis allowed them to propose exercise may improve regularity of menstruation, the rate of ovulation, and pregnancy rates in these women. Via meta-analysis, secondary outcomes of body measurement and metabolic parameters significantly improved after women with PCOS underwent exercise training; however, symptoms such as acne and hirsutism (excessive, abnormal body hair growth) were not changed with exercise. The authors concluded exercise does improve the metabolic health (ie, insulin resistance) in women with PCOS, but evidence is insufficient to measure the exact impact on the function of the reproductive system.

Increasing our knowledge about comorbidities such as PCOS, regardless of our practice setting, can help us provide better education to the patients we treat. Perhaps exercise compliance can increase when patients are told multiple long-term benefits, not just immediate symptom relief. More often than not, a patient’s 4-6 week interaction with us could motivate and promote healthy lifestyle changes.

Pericleous, P., & Stephanides, S. (2018). Can resistance training improve the symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome? BMJ Open Sport — Exercise Medicine, 4(1), e000372. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000372

Benham, J. L., Yamamoto, J. M., Friedenreich, C. M., Rabi, D. M. and Sigal, R. J. (2018), Role of exercise training in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Obes, 8: 275-284. doi:10.1111/cob.12258

Suggested newly published resource for readers…

Teede, H. J., Misso, M. L., Costello, M. F., Dokras, A., Laven, J., Moran, L., … Yildiz, B. O. (2018). Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 33(9), 1602–1618. http://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey256

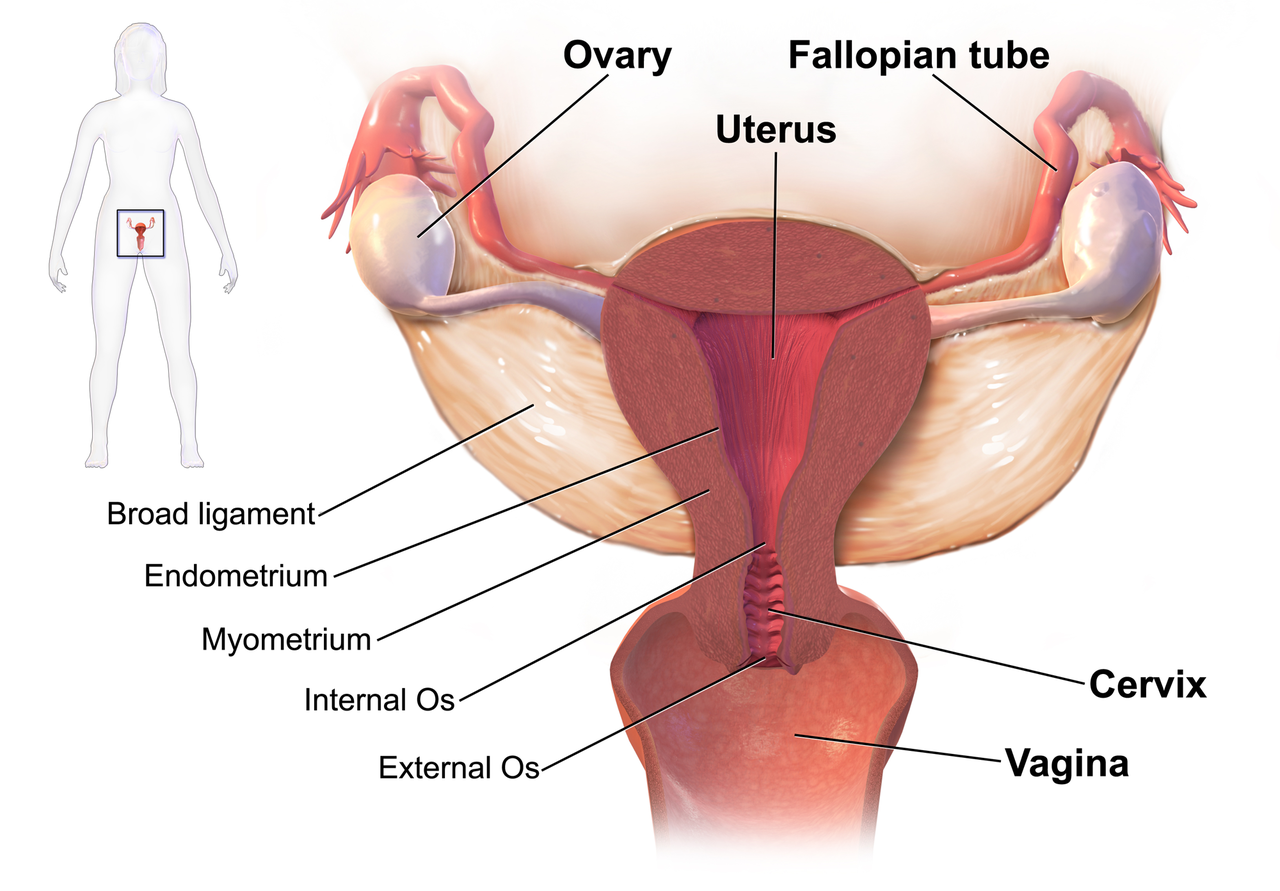

September is Gynae Cancer Awareness Month – but how aware are we as clinicians of the signs and symptoms, the epidemiology and the sequalae of treatment afterwards? As pelvic rehab specialists, we have the privilege of helping women live well after cancer treatment ends, both on a ‘local’ pelvic area (bladder, bowel, sexual and pelvic pain management strategies) but also on a more ‘global’ level – dealing with issues such as cancer related fatigue, bone health and cardiovascular concerns.

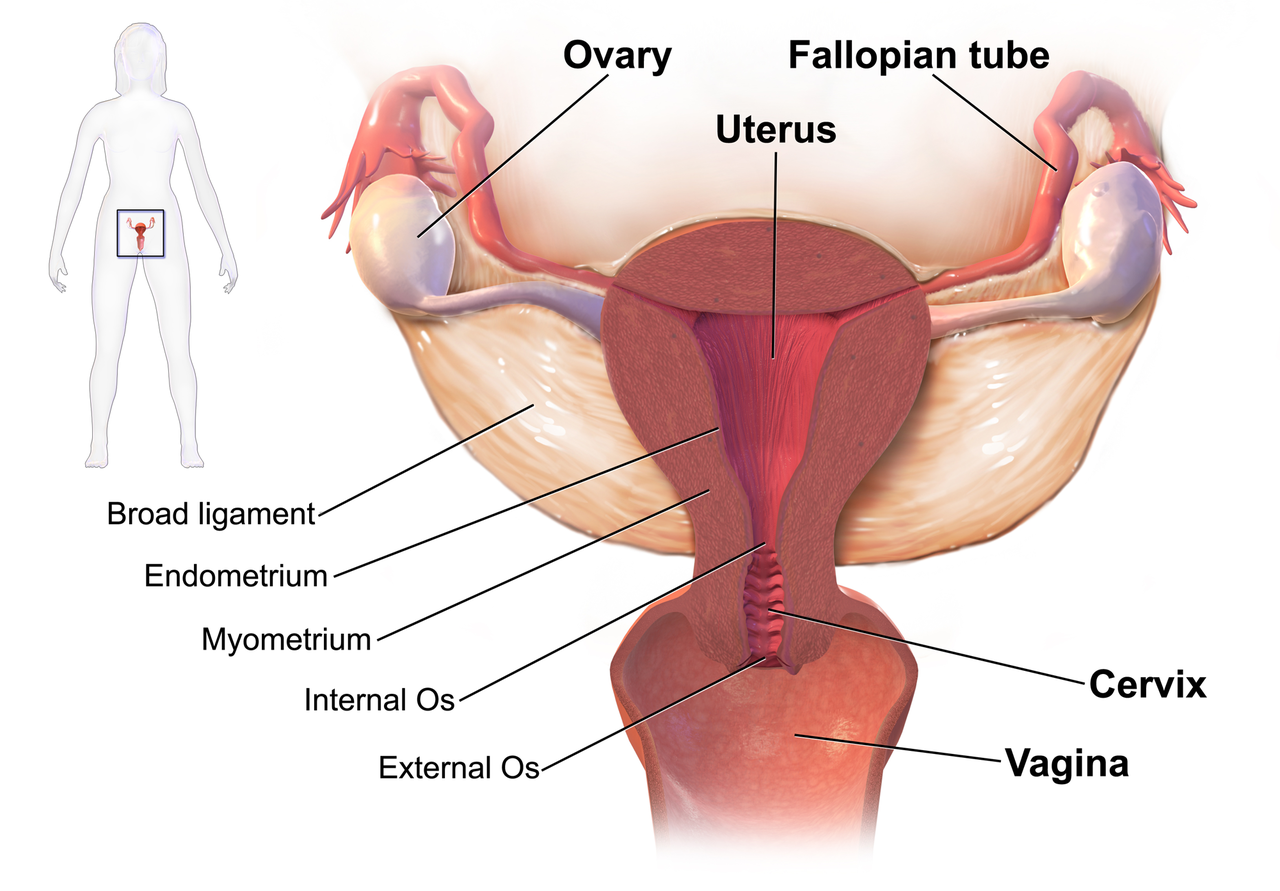

We know that women who are diagnosed with cancer of the vulva, vagina, cervix, endometrium or ovaries are treated with a combination of surgery, radiation or chemotherapy. However, with improving treatment and better survival rates, there is evidence that a variety of pelvic health concerns may arise for these women, both during and after treatment. (Hazewinkel et al 2010). For example, urinary incontinence is reported in 80% of women treated for endometrial cancer, with more severe symptoms and impact on quality of life in those who had adjuvant radiation (Erekson et al 2009) In Malone’s 2017 paper, ‘The patient’s voice: What are the views of women on living with pelvic floor problems following successful treatment for pelvic cancers?’, the author notes that ‘…there is currently a lack of knowledge regarding the effects of PFD on QoL in this cohort. Patients do not always report these problems to their health care providers and clinicians may underestimate symptoms…In the context of having survived cancer, PFD may be seen as relatively trivial. However, in the context of resuming normal living, the symptoms experienced by the survivors may be significant’.

We know that women who are diagnosed with cancer of the vulva, vagina, cervix, endometrium or ovaries are treated with a combination of surgery, radiation or chemotherapy. However, with improving treatment and better survival rates, there is evidence that a variety of pelvic health concerns may arise for these women, both during and after treatment. (Hazewinkel et al 2010). For example, urinary incontinence is reported in 80% of women treated for endometrial cancer, with more severe symptoms and impact on quality of life in those who had adjuvant radiation (Erekson et al 2009) In Malone’s 2017 paper, ‘The patient’s voice: What are the views of women on living with pelvic floor problems following successful treatment for pelvic cancers?’, the author notes that ‘…there is currently a lack of knowledge regarding the effects of PFD on QoL in this cohort. Patients do not always report these problems to their health care providers and clinicians may underestimate symptoms…In the context of having survived cancer, PFD may be seen as relatively trivial. However, in the context of resuming normal living, the symptoms experienced by the survivors may be significant’.

This can present a clinical conundrum – often pelvic rehab therapists are nervous when working with a patient who has a current or previous gynecologic cancer diagnosis, but similarly oncology rehab specialists may have qualms about dealing with pelvic health issues, with the result that these women fall through the cracks and do not have their pelvic health issues managed properly (or at all). Theodore Roosevelt once said ‘No one cares how much you know, until they know how much you care’ and this is especially relevant for oncology pelvic rehab. Often you may be the first clinician to ask about bladder, bowel or sexual function or dysfunction. An understanding of the effects of cancer treatments on the pelvis is important but so too is the wealth of information you may already have about bladder, bowel and sexual health as well as neuroscience and pain education.

The most important thing is to ask these women about their pelvic health concerns – the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship defined cancer survivorship as extending from ‘the time of diagnosis and for the balance of life’. An emphasis on quality of life has been emphasised – if we know that cancer survivors may not independently volunteer information about their pelvic floor dysfunction, it is our responsibility to ask the questions and comprehensively treat and advocate for these women, in order to help them live well after cancer treatment ends.

- Hazewinkel MH. Sprangers MA, Velden Jvd, Vaart CH, Stalpers LJ, Burger MP ‘Longterm cervical cancer survivors suffer from pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms: A cross-sectional matched cohort study’ Gynecol Oncol 2010;117(2):381-6

- Erekson EA, Sung VW, Disilvestro PA, Myers DL ‘Urinary symptoms and impact on quality of life in women after treatment for endometrial cancer’ Int Urogynecol J 2009;20(2):159-63

- Malone P, Danaher D, Galvin R, Cusack T ‘The patient’s voice: What are the views of women on living with pelvic floor problems following successful treatment for pelvic cancers?’ Physiotherapy Practice and Research 38(2017)93-102

The following is part two in a series documenting Deb Gulbrandson, PT, DPT's journey treating a 72 year old patient who has been living with multiple sclerosis (MS) since age 18. Catch up with Part one of the patient case study on the Pelvic Rehab Report here. Dr. Gulbrandson is a certified Osteoporosis Exercise Specialist and instructor of the Meeks Method, and she helps teach The Meeks Method for Osteoporosis course.

On Maryanne’s second visit, she reported she had been doing her “homework” and didn’t have any questions. Just to be sure, we reviewed them and I had her demonstrate. In Decompression position, she was lying supine with her hands on her abdomen, a common mistake I see. Usually this is due to tightness in pec minor with protracted scapulae. Patients unknowingly resort to the path of least resistance to take the strain off of the muscles. I explained to her that we want to use gravity to gently lengthen those muscles and “widen” the collarbones to allow for improved alignment. With her shoulders abducted to approximately 30 degrees and palms up, I propped a couple of small towels under her forearms which allowed her shoulders to relax into a more posterior and correct position.

“Today we begin the Re-alignment routine,” I said, “starting with the Shoulder Press.” I showed her how to gently press the back of her shoulders down into the mat without arching her lumbar spine. “As you press your shoulders down, exhale through your mouth as if you’re fogging a mirror. This will help activate your core muscles to keep your back in good alignment. Hold for 2-3 seconds, and then relax. Repeat 3 times.” Maryanne looked at me as if I’d lost my mind. “Did you say do 3 reps?” she asked. “I do 2 sets of 20 reps at the gym,” she said with obvious pride in her voice. “Yes, that’s where we start, and there are a couple of reasons. First, these are very site specific exercises which focus on the exact areas that need strengthening. Exercises done in a gym setting are often more general and usually involve compensation. We are minimizing any compensation such as allowing your low back to arch. There is probably weakness in those upper back muscles as well as the tightness seen in your anterior chest muscles and we need to go slowly. Also, we are simultaneously stretching while we strengthen. Our society is so forward biased (we work on computers, drive cars, make beds, eat- it’s all forward, forward, forward), that the anterior muscles get tight and the upper back muscles get overstretched and weak. We need to reverse that pattern. Take a look at our younger population and their texting postures. Yikes! We will be layering on more exercises as your technique improves so you’ll be doing more than just 3 reps, I promise.”

After the Shoulder Press we proceeded with the Head Press, Leg Lengthener and Arm Lengthener, spending time to make sure her cervical spine stayed in neutral as she pressed her head down into the mat. Head Press (cervical retraction) performed in supine allow patients to have something to press against and helps inhibit the tendency to move into cervical extension. It can also be done standing against the wall with a small pillow or folded towels between the occiput and the wall.

We ended with Maryanne in standing at the kitchen sink to promote functional activities and weight bearing positions. I reminded her to do the Foot Press through the floor using the Triangle of Foot Support visual. This helped to elongate her spine. “Imagine a bungie cord running from the top back of your head to the ceiling” I said which further increased her standing height. “Now I want you to imagine a shelf running straight out from your breastbone with a glass of some very expensive fine drink sitting on it. Do not spill your libation! Oh, and one last thing Maryanne. Breathe!!!” At which point she collapsed into laughter and our session was over. “Busted”, she said.