Transabdominal Ultrasound In The Assessment Of Abdominal And Pelvic Floor Muscles

Authors: Tamara Rial, PhD, CSPS, Kathleen Doyle-Elmer, PT, DPT and Rebecca Keller, PT, MSPT, PRPC

Tamara Rial, PhD, CSPS, co-founder and developer of Low Pressure Fitness will be presenting the first edition of Low Pressure Fitness and Abdominal Massage for Pelvic Floor Care Level 2 and 3 in Princeton, New Jersey in September, 2019. Rebecca Keller and Kathleen Doyle-Elmer are certified Low-Pressure Fitness specialists with training in rehabilitative ultrasound imaging. In this article, the authors discuss and explore the use of transabdominal ultrasound during Low Pressure Fitness on the abdominal and pelvic floor structures.

Real-time ultrasound imaging is a reliable and valid method to evaluate muscle structure, activity and mobility. Over the past few years, there has been increasing interest in the use of transabdominal ultrasound in the field of rehabilitation. The additional value of ultrasound imaging is that it allows for real-time analysis and visual feedback during the performance of pelvic floor and abdominal exercises (Hides et al., 1998). In the field of pelvic health, this is of notable importance when assessing proper movement of the deep abdominal and pelvic muscles during voluntary muscle actions. Transabdominal ultrasound has been found to be a safe, noninvasive, and accurate method to assess and observe muscular and fascial activity (Khorasani et al., 2012). When therapists learn how to properly use and apply ultrasound imaging, this technique can be a comprehensive tool for the clinician and a comfortable procedure for the patient. Moreover, it may be the method of choice for some patients who don’t want to have an internal pelvic examination (Van Delft, Thakar & Sultan, 2015). In this regard, a cross-sectional study found a moderate-to-strong correlation between ultrasound measurements and both digital examination and perineometry for the assessment of pelvic floor muscle actions (Volløyhaug et al., 2016).

Recently, Low Pressure Fitness has gained popularity as a pelvic floor training program aimed at reducing pressure on the pelvic structures while engaging the stabilizing muscles through postural and breathing exercises. In order to evaluate proper execution of Low-Pressure Fitness exercises as well as abdomino-pelvic muscle function during this type of training, real-time transabdominal ultrasound can be a clinically relevant tool.

Sagittal and Transverse Pelvic Floor/Urinary Bladder Assessment

The amount of movement of the bladder base on transabdominal ultrasound is considered an indicator of pelvic floor muscle mobility during pelvic floor muscle exercises (Khorasani et al., 2012). When properly executed, the Low-Pressure Fitness technique will allow the bladder to lift and the pelvic floor muscles to contract. These observed actions can be cued and progressed due to the real-time imaging biofeedback of the ultrasound. Because of the postural activation and diaphragm lift occurring during Low Pressure Fitness, the bladder fascial support system is tensioned resulting in a desirable bladder lift.

For example, we used a Pathway® Musculoskeletal Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging unit with a curvilinear transducer and Prometheus Pathway® rehabilitative ultrasound software utilizing the pre-set parameters (Abdominal Wall 7.5MHz and Bladder 5.0MHz) during a Low-Pressure Fitness basic supine posture. A standardized bladder filling protocol was used before imaging to ensure sufficient bladder filling to allow clear imaging of the base of the bladder and pelvic floor muscles.

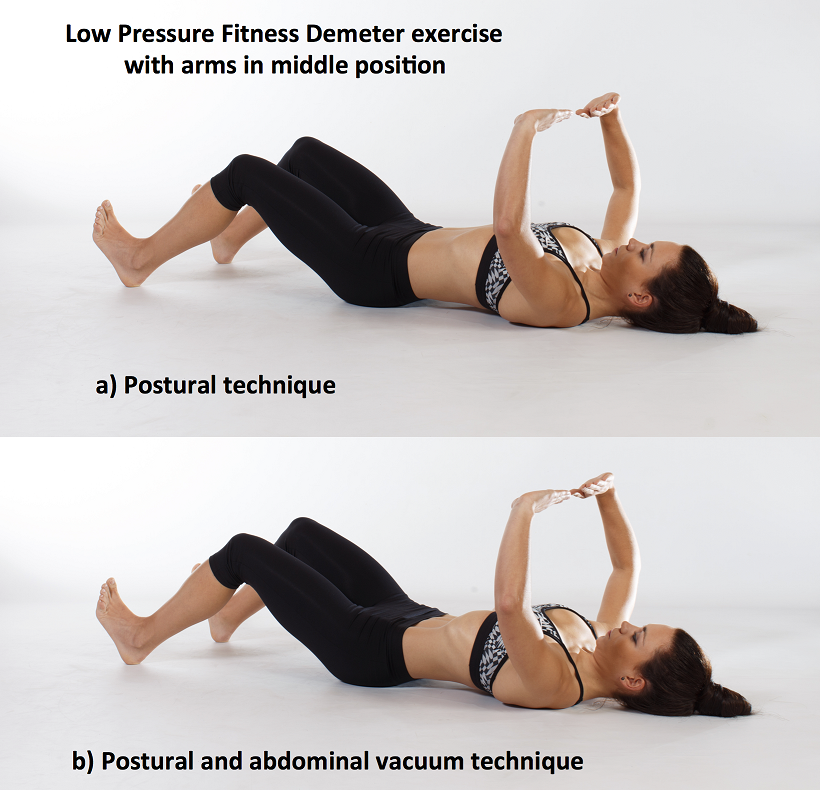

For the transverse view, radiologic standards were used, and the ultrasound transducer was placed in the transverse plane suprapubically and angled in a caudal/ posterior direction to obtain a clear image of the inferior-posterior aspect of the bladder. The participant was asked to perform the Low-Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise in the supine position with a neutral pelvis and knees flexed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Demeter exercise with postural technique and with postural and abdominal vacuum technique combined.

The following video illustrates the pelvic floor/urinary bladder during: a) resting position; b) active pelvic floor contraction; c) Low Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise and; d) Low Pressure Fitness Demeter exercise combined with a voluntary pelvic floor muscle contraction. It is noticeable a greater bladder lift and pelvic floor activation with the postural and breathing cueing added to an active pelvic floor contraction than with the pelvic floor contraction alone.

Video of the behavior of the pelvic floor muscles in a sagital and transversal view during the supine position of Low Pressure Fitness and with the combination of an active pelvic floor muscle contraction.

Lateral Abdominal Wall Assessment

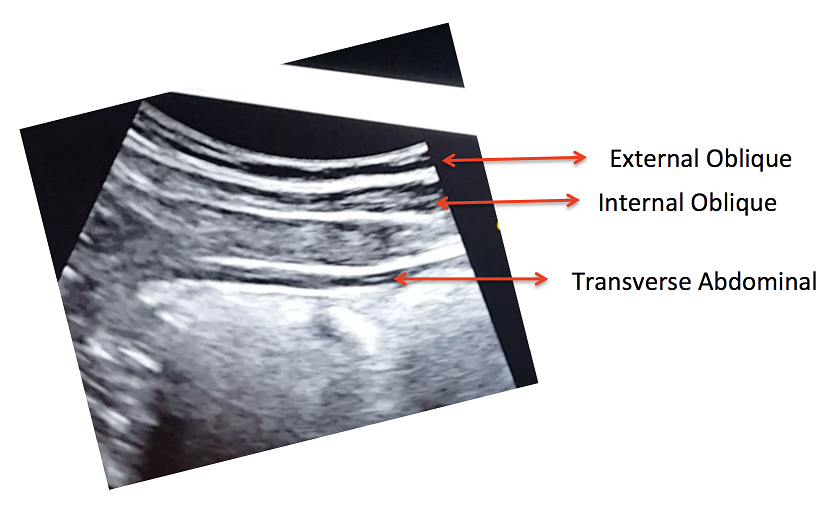

The lateral abdominal muscle ultrasound assessment allows us to observe the structural changes produced in the transversal section of the abdominal muscles in the midpoint between the anterior iliac crest and the costal angle. At low levels of contraction, the extent of transverse abdominis thickening measured using ultrasound is reported to be a valid method of assessment compared with either fine wire electromyographic measures of transverse activity (McMeeken et al., 2004). It is well established in the scientific literature that the lateral abdominal muscles provide stability to the trunk in different functional activities. Therefore, the assessment of the size, thickness and sliding of the abdominal wall is important for patients who present with lumbo-pelvic and/or pelvic floor dysfunctions. In this regard, patients with low back pain show different abdominal wall muscle activation patterns (i.e. less slide of the abdominal fascia and muscle thickness) than those without low back pain (Gildea et al., 2014; Unsgaard-Tondel et al., 2012).

Figure 2 shows the three muscle layers of the lateral wall in the resting position. The superficial layer corresponds to the external oblique, the middle layer to the internal oblique and the deep layer to the transverse abdominal muscle.

Figure 2. View of the right lateral abdominal wall at rest.

A key breathing component of the Low-Pressure Fitness program is the abdominal vacuum which manipulates intra-abdominal, intra-thoracic and intra-pelvic pressures during the breath-holding phase. Another key aspect of Low-Pressure Fitness is the shoulder girdle activation, spine elongation and ankle-dorsiflexion (Rial & Pinsach, 2017). Of note, previous studies have demonstrated greater transverse abdominis activation when performing ankle dorsi-flexion (Chon et al., 2010). We used transabdominal ultrasound to assess the lateral abdominal wall response during ankle dorsiflexion, shoulder girdle activation and the abdominal vacuum during Low Pressure Fitness.

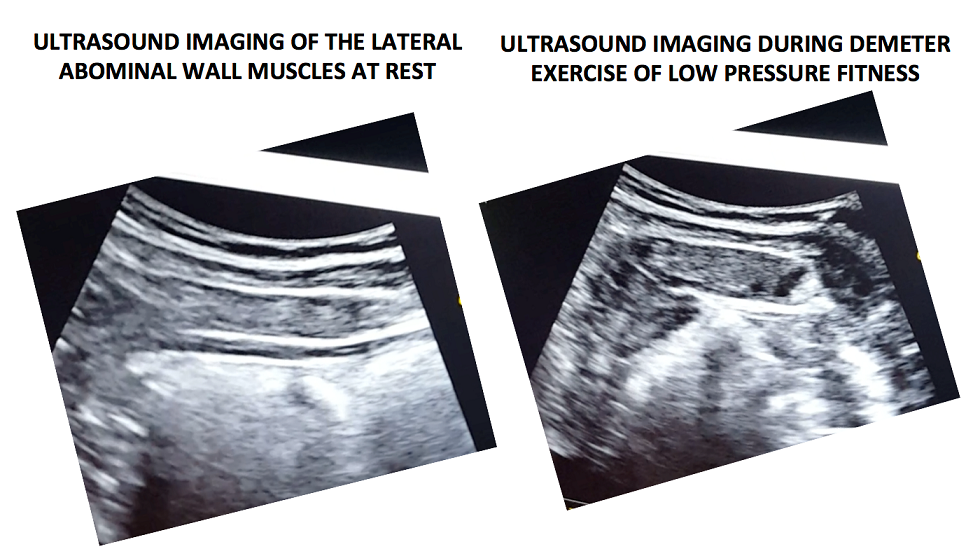

In the following video, a voluntary (active) abdominal contraction is performed in order to distinguish this action from the involuntary abdominal contractions during Low Pressure Fitness. Afterwards, the postural technique of ankle dorsiflexion and shoulder girdle activation are performed in the Demeter exercise with arms in middle position (Figure 1). Lastly, an abdominal vacuum maneuver is added to the postural technique. If the exercises are properly executed, the progressive sliding and thickness of the abdominal muscles throughout exercise sequence should be observable (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Ultrasound imaging at rest and during the complete LPF technique.

Video of a voluntary (active) abdominal contraction or draw-in maneuver is performed in order to distinguish this action from the involuntary abdominal contractions that occur during Low Pressure Fitness in a supine position

Muscle thickness of the transverse and internal oblique as well as a noticeable slide of the anterior abdominal fascia are observable during the Demeter exercise of Low-Pressure Fitness. This exercise pattern reflects an abdominal draw-in maneuver and a “corseting effect”. In this regard, notice the lateral pull or displacement of the edge of the anterior fascial insertion of the transverse the internal oblique muscle.

Navarro et al., (2017) used transabdominal ultrasound to assess the muscular responses of the pelvic floor and abdominal muscles in a group of women who underwent pelvic physiotherapy over two months. They found a significant increase in the transversal section of the transverse abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique muscles when compared to resting in the supine position. Similar to the position assessed by Navarro et al. (2017), we also assessed the pelvic floor and abdominal muscle responses during a Low-Pressure Fitness supine exercise.

Transabdominal ultrasound can provide a noninvasive and informative visual biofeedback when training patients with Low Pressure Fitness. This ultrasound imaging can be a valuable tool to both the client and the clinician to objectify progress, assist with validating correct Low-Pressure Fitness form with positioning and vacuum/hypopressive maneuver as well as a motivational technique for the client. As demonstrated during our rehabilitative ultrasound imaging, observable bladder lift, pelvic floor activation and desirable lateral abdominal muscular corseting (slide and thicking) occurs during Low Pressure Fitness postural exercises and breathing. Since Low Pressure Fitness is a progressive exercise program, qualified instruction, technique driven progression and understanding pelvic floor health are needed to optimize patient outcomes.

Chon SC, Chang KY, You JS. Effect of the abdominal draw-in manoeuvre in combination with ankle dorsiflexion in strengthening the transverse abdominal muscle in healthy young adults: a preliminary, randomised, controlled study. Physiotherapy 96: 130-6, 2017.

Gildea JE, Hides JA, Hodges PW. Morphology of the abdominal muscles in ballet dancers with and without low back pain: a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Sci Med Sport. 17(5): 452-6, 2014.

Khorasani B, Arab AM, Sedighi Gilani MA, Samadi V, Assadi H. Transabdominal ultrasound measurement of pelvic floor muscle mobility in men with and without chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology, 80: 673-7, 2012.

McMeeken JM, Beith ID, Newham DJ, Milligan P, Critchley DJ. The relationship between EMG and change in thickness of transversus abdominis. Clin Biomech 19: 337–342, 2004.

Hides JA, Richardson CA, Jull GA. Use of real-time ultrasound imaging for feedback in rehabilitation. Man Ther. 3:125-131,1998.

Navarro B, Torres M, Arranz B, Sanchez O. Muscle response during a hypopressive exercise after pelvic floor physiotherapy: Assessment with transabdominal ultrasound. Fisioterapia 39: 187-94, 2017.

Rial T, Pinsach P. Practical Manual Low Pressure Fitness Level 1. International Hypopressive & Physical Therapy Institute, Vigo, 2017.

Unsgaard-Tøndel M, Lund Nilsen TI, Magnussen J, Vasseljen O. Is activation of transversus abdominis and obliquus internus abdominis associated with long-term changes in chronic low back pain? A prospective study with 1-year follow-up. Br J Sports Med, 46(10): 729-34, 2012.

Van Delft K, Thakar R, Sultan AH. Pelvic floor muscle contractility: digital assessment vs transperineal ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 45: 217-22, 2015. Volløyhaug I, Mørkved S, Salvesen Ø, Salvesen KÅ. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle contraction with palpation, perineometry and transperineal ultrasound: a cross-sectional study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 47: 768-73, 2016.

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://www.hermanwallace.com/