HW faculty member Carole High Gross, PT, MS, DPT, PRPC instructs her remote course, Eating Disorders and Pelvic Health Rehabilitation, on October 19-20, 2024 that takes a deep dive into the role of pelvic health rehabilitation with individuals with eating disorders.

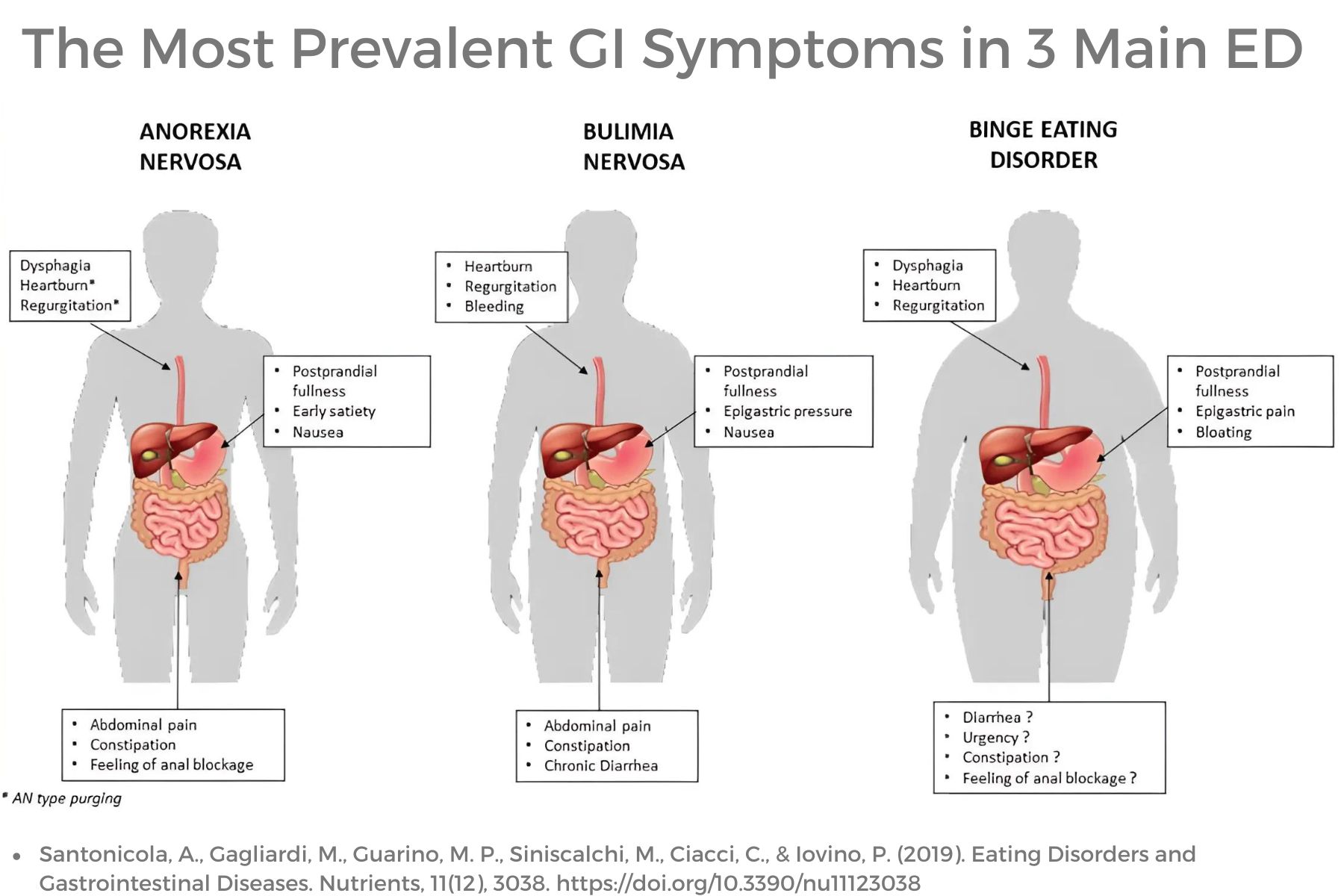

The role of a pelvic health rehabilitation professional includes caring for individuals with dysfunction within the pelvis and abdominal canister. We treat individuals with constipation, fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, urinary dysfunction, pelvic pain, abdominal pain, and bloating (to name a few). Individuals with eating disorders often experience ALL of these symptoms. Numerous studies demonstrate bowel, bladder, and pelvic dysfunction in those with eating disorders (see reference list for some of these studies). We CAN help!

Eating disorders are mental health conditions with serious biopsychosocial implications that negatively impact the function of the body, social interactions, and psychological well-being. The American Psychiatric Association characterizes Eating Disorders (ED) as “behavioral conditions characterized by severe and persistent disturbance in eating behaviors and associated distressing thoughts and emotions.” Types of eating disorders include:

- anorexia nervosa (AN)

- bulimia nervosa (BN)

- binge eating disorder (BED)

- avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

- other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED)

- pica and rumination disorder

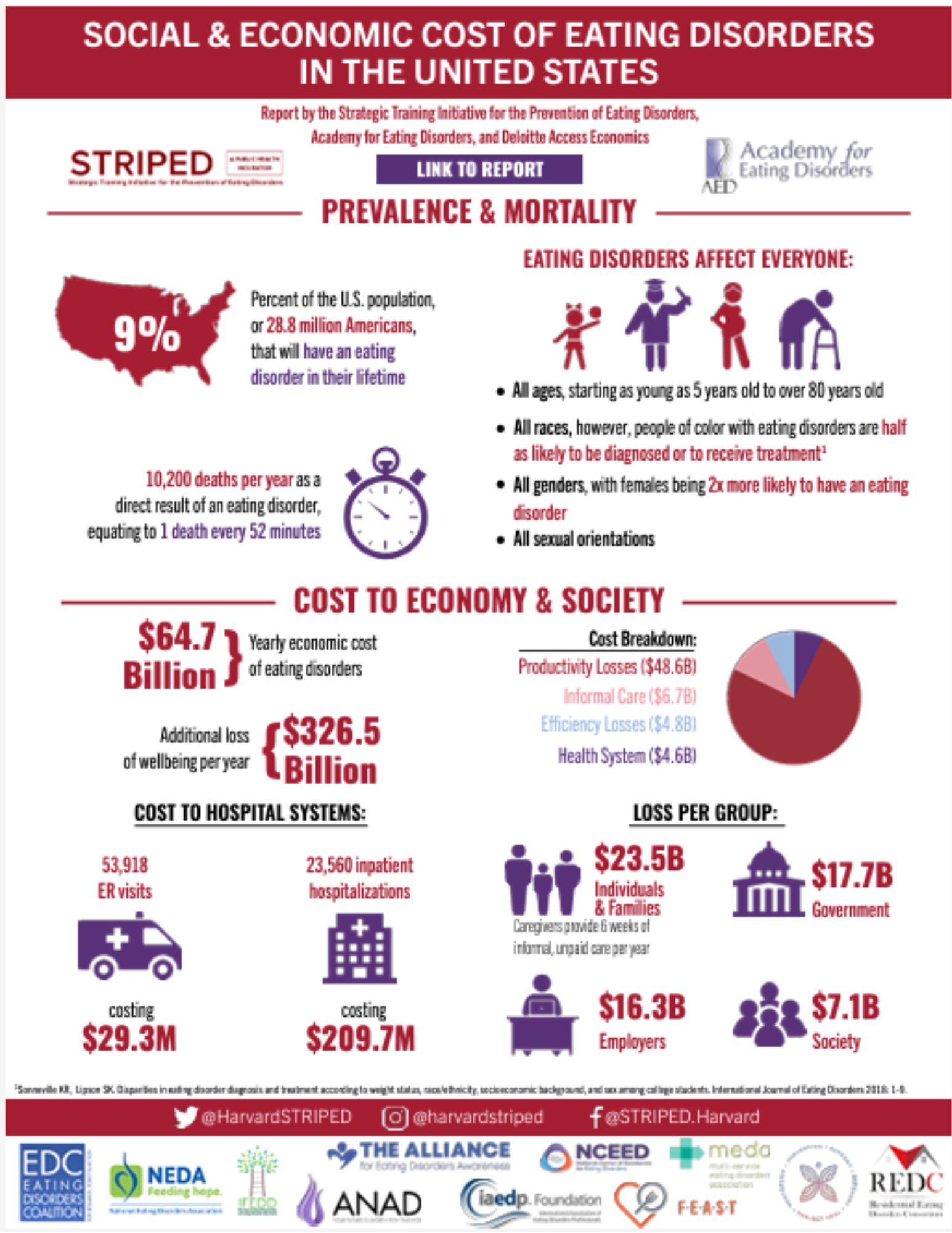

Eating disorders are estimated to affect roughly 5% of the population and are often under-reported and unidentified by the medical community. People of all genders often suffer in silence as eating disorders tend to be a very secretive and all-consuming mental illness that does not discriminate based on gender, culture, race, or nationality. Eating disorders can develop at any time in someone’s life, however, often signs develop in adolescence and early adulthood.

Supporting Research

One noteworthy article, which was published in May of 2024, was written by Monica Williams and colleagues from ACUTE, an inpatient eating disorder treatment facility, in Denver, Colorado. Williams et al. published a retrospective cohort study of 193 female women highlighting pelvic floor dysfunction in people with eating disorders. This study illustrated the positive effects of management (including education, pelvic floor muscle assessment, biofeedback, and active retraining of the pelvic muscle) on pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) with the intervention group (n=84). Each of the patients in this study had only one to a few treatment sessions of selected appropriate interventions.

Williams et al. published a retrospective cohort study of 193 female women highlighting pelvic floor dysfunction in people with eating disorders. This study illustrated the positive effects of management (including education, pelvic floor muscle assessment, biofeedback, and active retraining of the pelvic muscle) on pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) with the intervention group (n=84). Each of the patients in this study had only one to a few treatment sessions of selected appropriate interventions.

The control group received the standard of care education including mindfulness, relaxation techniques, and diaphragmatic breathing. All participants in the intervention group received a 30-minute education session which included the purpose of the pelvic floor, causes of pelvic floor dysfunction, the relationship between the pelvic floor and diaphragm, typical bladder norms, strategies to improve bowel/bladder emptying and urge suppression techniques. The Education Group (n=26) received education only without other interventions. Although this group showed improvements in the PFDI score, the improvements did not meet statistically meaningful improvement in pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms. However, the other treatment subgroups within the intervention group showed statistically meaningful improvements in pelvic floor dysfunction. The Pelvic Floor Assessment group (n=13) included individuals who received the education (noted above) and internal assessment of pelvic floor musculature with the goal of improving coordination of PFM.

The Urinary Distress Inventory 6 (UDI-6) demonstrated statistically significant improvement in the Pelvic Floor Assessment Group. The UDI-6, the Colorectal-Anal Inventory 6 (CRAD-8), and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory 6 (POPDI-6) improved with the Active Retraining (of the pelvic floor muscles) Group (n=67). The individuals in the Active Retraining group received: Education (mentioned above) and bladder training (improving time between voids) and pelvic floor stretches (deep squat, butterfly, child’s pose, happy baby including coordination of diaphragmatic breathing and movement of the pelvic floor). The Biofeedback Group (n=3) received Education (mentioned above) and biofeedback including visual feedback to instruct patients on how to effectively contract and relax PFM. The Biofeedback Group showed statistical improvement with the POPDI-6 score.

Overall, Williams et al. concluded that patients with eating disorders report an increased level of pelvic floor symptoms. The interventions provided in this study were found to be beneficial. Individuals with the anorexia binge-purge subtype also had higher scores on the PFDI than the anorexia nervosa restricting subtype. The authors recommended future studies to better describe the etiology of PFD in individuals with ED and how PFD contributes to both behaviors and GI symptoms of those with eating disorders.

Ng et al., 2022, discussed research that demonstrated the relationship between eating disorders and urinary incontinence through the lens of psychoanalysis. This article described mental health co-morbidities with eating disorders that contribute to urinary dysfunction. The authors also encouraged a good psychodynamic understanding of childhood relationships, personality traits, and the inner mental “landscape.” The authors reinforced mental co-morbidities contribute to increased urinary incontinence and dysfunction including poor interoceptive awareness, personality traits, decreased life satisfaction, need for control, and anxiety.

This article described mental health co-morbidities with eating disorders that contribute to urinary dysfunction. The authors also encouraged a good psychodynamic understanding of childhood relationships, personality traits, and the inner mental “landscape.” The authors reinforced mental co-morbidities contribute to increased urinary incontinence and dysfunction including poor interoceptive awareness, personality traits, decreased life satisfaction, need for control, and anxiety.

Ng and colleagues described the prominence of poor interoceptive awareness among individuals with eating disorders. Interoceptive awareness refers to awareness of one’s feelings or emotions. This may also affect a person’s perception of stimuli arising in the body, such as to perform bodily functions such as urination. Poor interoceptive awareness would likely also play a factor in awareness of the body’s need to evacuate stool however, this was not within the scope of this article. Bowel dysfunction with ED is well documented in the research.

Ng et al’s article also discusses common personality traits among individuals with some eating disorders including perfectionism and asceticism. Asceticism refers to the self-denial of physical or psychological desires or needs and can also be viewed as a ritualization of life. Often this refers to spirituality or religious practices, however, denial of bodily urges and the need for control is a common characteristic with some eating disorders which include restriction (AN, BN, OSFED). Denial of basic needs, such as urination, would reasonably reinforce the need for control. Often those with restrictive eating disorders excessively control what goes into the body and may also be restricting what is coming out of the body including feces and urine.

Anxiety and other mental health comorbidities are common in individuals with ED and can contribute to increased tone and tension in the pelvic floor contributing to urinary dysfunction. Additional research supports that this increased pelvic tone and tension also contributes to sexual dysfunction, pelvic pain, and bowel dysfunction in individuals with and without eating disorders. Mental health challenges may also lead to closed posturing, tightness in the back, hip, and shoulder musculature as well as upper chest breathing, and poor excursion of the diaphragm.

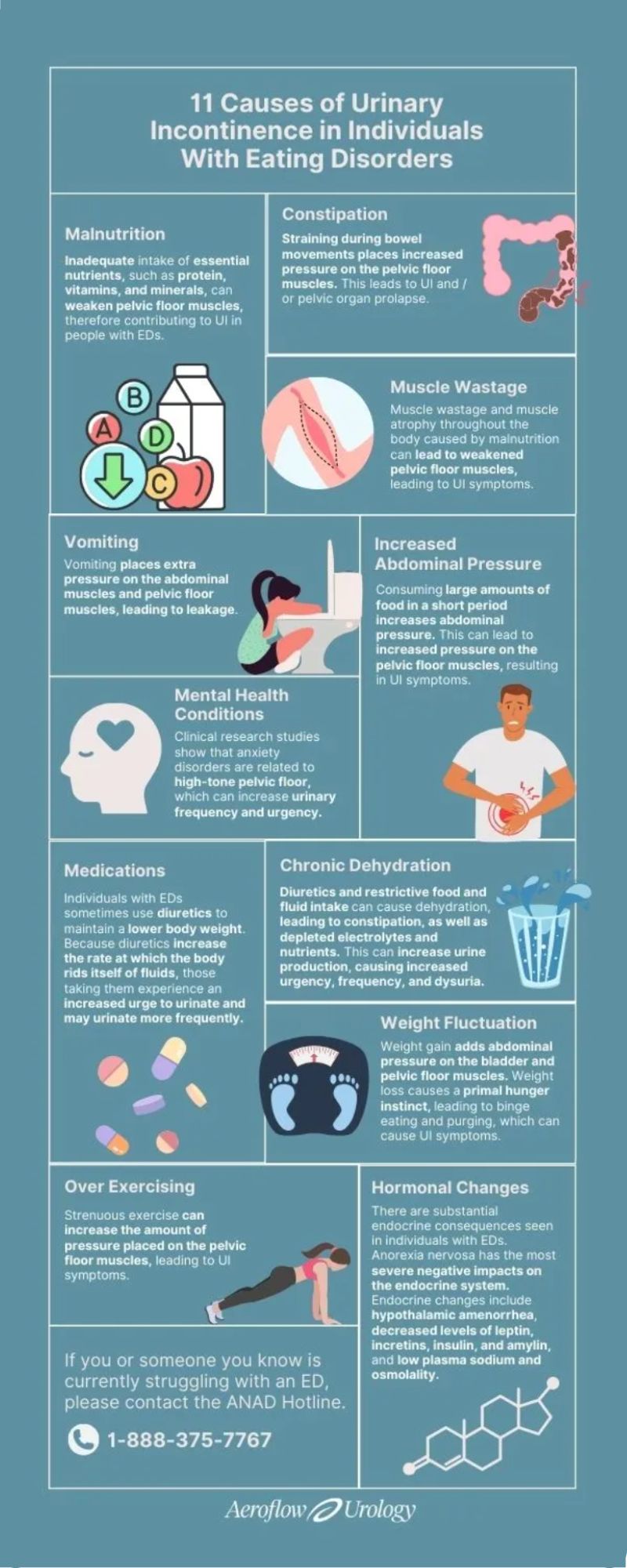

As pelvic health rehabilitation providers, we need to look at the whole person as so many factors influence pelvic-related dysfunction. Numerous factors affect bowel, bladder, and pelvic function including muscle wasting and atrophy, slow GI motility, medications, hormonal changes, weight fluctuations, purging behaviors, poor pressure management, increased intra-abdominal pressure, mental wellness comorbidities, excessive exercise, water loading, dehydration, malnutrition, poor postural alignment, length and tension of muscular and fascial systems, diaphragmatic/lower costal excursion and diversity of microbiome to name a few.

Septak posted a blog in February 2024 for the aeroflowurology.com website that discussed factors that negatively impact bladder control in individuals with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa based on research.

The author discussed research implying muscle wasting and atrophy caused by malnutrition can lead to weakness in pelvic floor musculature and support structures. This contributes to urinary symptoms, however, also contributes to bowel dysfunction. The musculature around the colon when not used will atrophy and weaken.

Purging behaviors have numerous negative and potentially dangerous effects on the body function of individuals with eating disorders. Vomiting will increase pressure on PFM, pelvic organs, and abdominal musculature. Laxative use will lead to fecal issues such as fecal incontinence and can contribute to increased pressure and trauma on pelvic organs/musculature. Purging will also lead to serious electrolyte imbalances which can lead to organ system dysfunction or failure.

Other medications also influence bowel and bladder function such as diuretics, which are often mis-utilized to lower body weight through the rapid loss of body fluids. Individuals with DM Type 1 may also withhold insulin to result in a diuretic effect. This not only disrupts essential body electrolytes, but it will also lead to dehydration contributing to bowel dysfunction such as constipation. Diuresis of fluids will also increase urinary urgency, frequency, and risk for incontinence.

Constipation may be caused by numerous factors including dehydration, muscle wasting, slow motility, decreased gastric emptying, and poor nutritional intake. Upregulation of the sympathetic nervous system with trauma history, personality traits, and numerous mental health comorbidities such as anxiety, OCD, and depression, play a significant role in constipation. Bowel movement straining places excessive stress on pelvic organs, pelvic musculature, fascia, and suspension structures, as well as the abdominal wall musculature and fascia. Constipation also contributes to urinary dysfunction due to the proximity of pelvic organs and can lead to pelvic organ prolapse.

Hormonal changes due to endocrine dysfunction with eating disorders, such as with AN, BN, and OSFED, can lead to disruptions in body system function. Hormonal disruptions often lead to hypothalamic amenorrhea, reduced levels of important levels of leptin (regulates appetite, energy balance, and metabolism), insulin (regulates blood sugar and is responsible for storage of incoming food as fat/ fuel), incretins (regulates blood sugar by stimulating pancreas to produce insulin), amylin (may contribute to low bone density with AN), plasma sodium and altered osmolarity (may result in nausea, vomiting, energy loss, confusion, seizures, heart, liver, kidney dysfunction). In addition, there are disruptions with other essential electrolytes that can contribute to body organ system malfunction and failure.

As pelvic health rehabilitation providers, we know how to treat pelvic and abdominal dysfunction.

We may, in fact, be the first healthcare professional who asks the important questions or makes insightful observations that illuminate a person’s secret struggle in the darkness. We may be able to lead these individuals to healthcare providers who are skilled in diagnosing, managing, and guiding that individual into the light of recovery. While we do not treat eating disorders, we DO treat the dysfunction caused by eating disorders. So many individuals with eating disorders will benefit from our education and interventions to assist them on their recovery journey.

Join Carole High Gross, PT, MS, DPT, PRPC in Eating Disorders and Pelvic Health Rehabilitation on October 19-20 for a deep dive into the role of pelvic health rehabilitation with individuals with eating disorders. We will discuss the different eating disorders, medical complications, signs and symptoms, screening and observations, interventions, and treatment approaches.

References:

- Abbate-Daga, G., Delsedime, N., Nicotra, B., Giovannone, C., Marzola, E., Amianto, F., & Fassino, S. (2013). Psychosomatic syndromes and anorexia nervosa. BMC psychiatry, 13, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-14[31]

- Abraham, S., Luscombe, G. M., & Kellow, J. E. (2012). Pelvic floor dysfunction predicts abdominal bloating and distension in eating disorder patients. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 47(6), 625–631. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2012.661762

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision DSM- 5TR. Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Press. 2022.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Press. 2013.

- Andersen AE, Ryan GL. Eating disorders in the obstetric and gynecologic patient population [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;116(5):1224]. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1353-1367. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c070f9

- Bodner-Adler, B., Alarab, M., Ruiz-Zapata, A. M., & Latthe, P. (2020). Effectiveness of hormones in postmenopausal pelvic floor dysfunction-International Urogynecological Association research and development-committee opinion. International urogynecology journal, 31(8), 1577–1582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04070-0

- Bulik CM, Reba L, Siega-Riz AM, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Anorexia nervosa: definition, epidemiology, and cycle of risk. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37 Suppl:S2-S21. doi:10.1002/eat.20107

- Carvalhais A, Araújo J, Natal Jorge R, Bø K. Urinary incontinence and disordered eating in female elite athletes. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22(2):140-144. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2018.07.008

- Castellini, G., Lelli, L., Ricca, V., & Maggi, M. (2016). Sexuality in eating disorders patients: etiological factors, sexual dysfunction and identity issues. A systematic review. Hormone molecular biology and clinical investigation, 25(2), 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1515/hmbci-2015-0055

- Chiarioni, G., Bassotti, G., Monsignori, A., Menegotti, M., Salandini, L., Di Matteo, G., Vantini, I., & Whitehead, W. E. (2000). Anorectal dysfunction in constipated women with anorexia nervosa. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 75(10), 1015–1019. https://doi.org/10.4065/75.10.1015

- Cortes, E., Singh, K., & Reid, W. M. (2003). Anorexia nervosa and pelvic floor dysfunction. International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction, 14(4), 254–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-003-1082-z

- Dobinson A, Cooper M, Quesnel D. Safe Exercise at Every Stage: A Guideline for Managing Exericse in Eating Disorder Treatment. https://www.safeexerciseateverystage.com/sees-guidelines

- Dreznik, Z., Vishne, T. H., Kristt, D., Alper, D., & Ramadan, E. (2001). Rectal prolapse: a possibly underrecognized complication of anorexia nervosa amenable to surgical correction. International journal of psychiatry in medicine, 31(3), 347–352. https://doi.org/10.2190/3987-2N5A-FJDG-M89F

- Dunkley CR, Gorzalka BB, Brotto LA. Associations Between Sexual Function and Disordered Eating Among Undergraduate Women: An Emphasis on Sexual Pain and Distress. J Sex Marital Ther. 2020;46(1):18-34. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2019.1626307

- Durnea, C. M., Khashan, A. S., Kenny, L. C., Tabirca, S. S., & O'Reilly, B. A. (2014). An insight into pelvic floor status in nulliparous women. International urogynecology journal, 25(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2225-5

- Emerich Gordon, K., & Reed, O. (2020). The Role of the Pelvic Floor in Respiration: A Multidisciplinary Literature Review. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation, 34(2), 243–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.09.024

- Gaudiani, J. L. (2019). Sick enough: a guide to the medical complications of eating disorders. Routledge.

- Gibson, D., Watters, A., & Mehler, P. S. (2021). The intersect of gastrointestinal symptoms and malnutrition associated with anorexia nervosa and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: Functional or pathophysiologic?-A systematic review. The International journal of eating disorders, 54(6), 1019–1054. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23553

- Gibson, D., Workman, C., & Mehler, P. S. (2019). Medical Complications of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa. The Psychiatric clinics of North America, 42(2), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2019.01.009Gong, R., & Xia, Z. (2019). Collagen changes in pelvic support tissues in women with pelvic organ prolapse. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology, 234, 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.01.012

- Guarda A. (2023, February). What are Eating Disorders? . American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders

- Harm-Ernandes, I., Boyle, V., Hartmann, D., Fitzgerald, C. M., Lowder, J. L., Kotarinos, R., & Whitcomb, E. (2021). Assessment of the Pelvic Floor and Associated Musculoskeletal System: Guide for Medical Practitioners. Female pelvic medicine & reconstructive surgery, 27(12), 711–718. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPV.0000000000001121

- Imgart H, Zanko A, Lorek S, Schlichterle PS, Zeiler M. Exploring the link between eating disorders and persistent genital arousal disorder/genito-pelvic dysesthesia: first description and a systematic review of the literature. J Eat Disord. 2022;10(1):159. Published 2022 Nov 10. doi:10.1186/s40337-022-00687-7

- Juszczak, K., & Thor, P. J. (2012). The integrative function of vagal nerves in urinary bladder activity in rats with and without intravesical noxious stimulation. Folia medica Cracoviensia, 52(1-2), 5–16.

- Karwautz, A. F., Wagner, G., Waldherr, K., Nader, I. W., Fernandez-Aranda, F., Estivill, X., Holliday, J., Collier, D. A., & Treasure, J. L. (2011). Gene-environment interaction in anorexia nervosa: relevance of non-shared environment and the serotonin transporter gene. Molecular psychiatry, 16(6), 590–592. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2010.125

- Keel, P. K., Eckel, L. A., Hildebrandt, B. A., Haedt-Matt, A. A., Murry, D. J., Appelbaum, J., & Jimerson, D. C. (2023). Disentangling the links between gastric emptying and binge eating v. purging in eating disorders using a case-control design. Psychological medicine, 53(5), 1947–1954. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721003640

- Kim H, Jung HR, Kim JB, Kim DJ. Autonomic Dysfunction in Sleep Disorders: From Neurobiological Basis to Potential Therapeutic Approaches. J Clin Neurol. 2022;18(2):140-151. doi:10.3988/jcn.2022.18.2.140

- Laino, F. M., de Araújo, M. P., Sartori, M. G. F., de Aquino Castro, R., Santos, J. L. F., & Tamanini, J. T. N. (2023). Urinary incontinence in female athletes with inadequate eating behavior: a case-control study. International urogynecology journal, 34(2), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-022-05349-5

- Leonardo, K., Seno, D. H., Mirza, H., & Afriansyah, A. (2022). Biofeedback-assisted pelvic floor muscle training and pelvic electrical stimulation in women with overactive bladder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurourology and urodynamics, 41(6), 1258–1269. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.24984

- Marjoux, Sophie & Bennadji, Boubekeur & de Parades, Vincent & Mosnier, Henri & Atienza, Patrick & Barth, Xavier & François, Yves & Faucheron, Jean & Roman, Sabine & Mion, Francois & Damon, Henri. (2012). Mo1059 Rectal Prolapse and Anorexia Nervosa: About 24 Cases. Gastroenterology. 142. S-584. 10.1016/S0016-5085(12)62240-9.

- Mazi, B., Kaddour, O., & Al-Badr, A. (2019). Depression symptoms in women with pelvic floor dysfunction: a case-control study. International journal of women's health, 11, 143–148. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S187417

- Micali N, Martini MG, Thomas JJ, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of eating disorders amongst women in mid-life: a population-based study of diagnoses and risk factors. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):12. Published 2017 Jan 17. doi:10.1186/s12916-016-0766-4

- Micali N, Treasure J, Simonoff E. Eating disorders symptoms in pregnancy: a longitudinal study of women with recent and past eating disorders and obesity. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(3):297-303. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.05.003

- Mitchell, N., & Norris, M. L. (2013). Rectal prolapse associated with anorexia nervosa: a case report and review of the literature. Journal of eating disorders, 1, 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-2974-1-39

- Ng QX, Lim YL, Loke W, Chee KT, Lim DY. Females with Eating Disorders and Urinary Incontinence: A Psychoanalytic Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4874. Published 2022 Apr 17. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084874

- Nitsch, A., Watters, A., Manwaring, J., Bauschka, M., Hebert, M., & Mehler, P. S. (2023). Clinical features of adult patients with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder presenting for medical stabilization: A descriptive study. The International journal of eating disorders, 56(5), 978–990. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23897

- Onur, Ö. Ş., & Teksin, G. (2023). Clinical Features of Women with Genito-Pelvic Pain, Penetration Disorder and Disordered Eating Attitudes: A Cross Sectional Study. Noro psikiyatri arsivi, 60(4), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.29399/npa.28313

- Panariello F, Borgiani G, Bronte C, et al. Eating Disorders and Disturbed Eating Behaviors Underlying Body Weight Differences in Patients Affected by Endometriosis: Preliminary Results from an Italian Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):1727. Published 2023 Jan 18. doi:10.3390/ijerph20031727

- Paslakis G, de Zwaan M. Clinical management of females seeking fertility treatment and of pregnant females with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2019;27(3):215-223. doi:10.1002/erv.2667

- Peinado-Molina, R. A., Hernández-Martínez, A., Martínez-Vázquez, S., Rodríguez-Almagro, J., & Martínez-Galiano, J. M. (2023). Pelvic floor dysfunction: prevalence and associated factors. BMC public health, 23(1), 2005. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16901-3

- Prescott SL, Liberles SD. Internal senses of the vagus nerve. Neuron. 2022;110(4):579-599. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2021.12.020

- Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: new insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S86-S90. doi:10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.17

- Schmidt U, Sharpe H, Bartholdy S, et al. Treatment of anorexia nervosa: a multimethod investigation translating experimental neuroscience into clinical practice. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; August 2017.

- Silvernale, Casey & Kuo, Braden & Staller, Kyle. (2020). Sa1678 PELVIC FLOOR PROLAPSE ASSOCIATED WITH GI-SPECIFIC HEALTHCARE UTILIZATION AND ANOREXIA NERVOSA IN AN EATING DISORDER PATIENT COHORT. Gastroenterology. 158. S-379. 10.1016/S0016-5085(20)31642-5.

- Tobias A, Sadiq NM. Physiology, Gastrointestinal Nervous Control. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; September 26, 2022.

- Vrijens, D., Berghmans, B., Nieman, F., van Os, J., van Koeveringe, G., & Leue, C. (2017). Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and their association with pelvic floor dysfunctions-A cross sectional cohort study at a Pelvic Care Centre. Neurourology and urodynamics, 36(7), 1816–1823. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23186

- Weigel, A., Löwe, B., & Kohlmann, S. (2019). Severity of somatic symptoms in outpatients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. European eating disorders review : the journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 27(2), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2643

- Williams, M., Blalock, D., Foster, M., Mehler, P. S., & Gibson, D. (2024). Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in People with Eating Disorders and the Acute Effect of Different Interventions – A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology, 51(5), 116. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.ceog5105116

- Worman, R. S., Stafford, R. E., Cowley, D., Prudencio, C. B., & Hodges, P. W. (2023). Evidence for increased tone or overactivity of pelvic floor muscles in pelvic health conditions: a systematic review. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 228(6), 657–674.e91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2022.10.027.

- Wojcik, M. H., Meenaghan, E., Lawson, E. A., Misra, M., Klibanski, A., & Miller, K. K. (2010). Reduced amylin levels are associated with low bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone, 46(3), 796–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2009.11.014

- Zachovajeviene, B., Siupsinskas, L., Zachovajevas, P., Venclovas, Z., & Milonas, D. (2019). Effect of diaphragm and abdominal muscle training on pelvic floor strength and endurance: results of a prospective randomized trial. Scientific reports, 9(1), 19192. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-55724-4

AUTHOR BIO:

Carole High Gross, PT, MS, DPT, PRPC

Carole High Gross, PT, MS, DPT, PRPC (she/her) earned her Doctorate of Physical Therapy from Arcadia University in 2015, and her Masters of Science in Physical Therapy in 1992 from Thomas Jefferson University. Carole earned her Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification and enjoys working as a Pelvic Clinical Rehabilitation Specialist for Lehigh Valley Health Network. Carole serves as a Lead Teaching Assistant for the Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute for pelvic floor education courses. She is also an instructor with the Herman and Wallace Institute for Eating Disorders and Pelvic Health Rehabilitation: The Role of a Rehab Professional. Carole serves on the Pelvic Workgroup of the Ehlers-Danlos International Consortium. Carole has a special interest in working with individuals living with eating disorders, and hypermobility throughout the pregnancy and postpartum journey. In addition, Carole enjoys working with all genders with pelvic, bowel, bladder, and abdominal issues. Carole is passionate about lifelong learning. She resides in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and enjoys spending time with her family and pups.

Join me on April 22 to begin this quest to learn more about signs, symptoms, and the journey that individuals with eating disorders endure. We will also explore ways that we as Pelvic Health Professionals can assist them on this journey in Eating Disorders and Pelvic Health Rehabilitation. This course will not have all the answers; rather will be a step forward for clinicians to expand their understanding and to seek out additional resources to learn more and provide evidence-based treatment for these individuals.

We, as pelvic health practitioners are NOT going to treat eating disorders… we are NOT going to diagnose eating disorders… but we CAN and SHOULD be asking questions… encouraging patients to seek additional support… and helping them find appropriately trained providers. We can ALSO provide support and speak with words that promote validation, wellness, and healing rather than words that are unintentionally triggering, harmful or nonvalidating. IN ADDITION, we can provide these individuals with manual skills, activities, and educational “tools'' to assist in GI distress, constipation, abdominal bloating, urinary dysfunction, pelvic pain, sexual dysfunction, POP issues, postural / body mechanics, abdominal canister coordination/function, tightness in trunk, hips, shoulders, rib cage, etc. These individuals would benefit from pelvic health professionals being an additional part (not the lead) of their treatment team.

We, as pelvic health professionals, need to: know what eating disorders are and are not, understand how this mental illness creates issues in all body functions, and what we can do to provide relief or reduction in some of their symptoms.

These case scenarios may be familiar or may have occurred without our awareness. These scenarios are based on real lives…and we likely see similar situations like this almost every day…

_____________________________________________________________________

Hope

Hope is a 31-year-old woman with an eight-year-old daughter with special needs. She is in your office for the second episode of care as she had COVID and her grandmother became terminally ill. Hope had come to PT before for severe abdominal pain and bowel dysfunction after a perforated colon during an ovarian cyst removal which resulted in a perforation in her colon, hemicolectomy, sepsis, and traumatic ICU hospitalization.

She had offered to you during her first episode of care that she had a history of anorexia. She was walking 7-9 miles a day, doing yoga 5 days a week, and seeing chiropractic care for fibromyalgia and chronic pain in the back/neck. She had been seeing an eating disorder mental wellness therapist and an eating disorder dietician for a while but had not seen them for some time. At the time of her first couple of visits, she was encouraged to make an appointment with both a mental wellness therapist and a dietician who both focused on eating disorders with who she was comfortable in the past. She agreed to do this but then stopped coming to therapy as mentioned above due to COVID and family emergencies.

When she came back to therapy, she looked much different. Her eyes were sunken, she had a thin layer of hair (lanugo) over her cheeks (what could be seen with the mask) and over her abdomen. Her fingernails were brittle and split.

She reported today that she has lost 25 more pounds because she thought that would help with the abdominal pain. Her new dietician (NOT an ED dietician) had her keeping a log of her food and has told her, according to Hope, that her body does not need more than 1500 calories a day and that she was eating “way too much”. She now logs everything she eats and counts calories.

Hope describes how she is now staying with her grandmother during the day in a skilled nursing facility and is supporting her grandfather. She is also caring for her 8-year-old daughter with special needs who is now in school during the day. She continues to exercise every day no matter what and is now not only walking the 7-9 miles but she is now doing strength training 4 days a week and yoga about 3-5 days a week. She seems to be almost superhuman as she juggles and manages all of these difficult situations.

After assessment of orthostatics, and standing blood pressure - her systolic BP dropped 25 mmHG and diastolic BP dropped 10 mmHg and her heart rate increased by 25 bpm after 5 minutes standing.

What might be some red flags here? What might your recommendations be? Who would you contact?

_____________________________________________________________________

Faith

Faith is a 24-year-old woman who came to pelvic floor physical therapy for urinary incontinence and dyspareunia which began after the cesarean section birth of her first child six months ago. She does not understand why she has all of the extensive "stretch marks" on her abdomen and why her cesarean section scar looks so large. She is very unhappy about how her body looks after giving birth.

Upon further conversation, she shares that she only eats a “super clean diet” and has cut out major food groups such as dairy, sugar, and meat because those foods are "high in calories" and "not healthy". She sparingly consumes any carbs and mainly eats vegetables and some fish sometimes.

She has experienced episodes of lightheadedness and near syncope for years. She reports that has been very “bendy” and was a cheerleader in high school. Faith has had painful joints and subluxations in her hips and knees for as long as she can remember.

Faith also shares that it is always so tiring. She also reports that she worries a lot about her newborn and is having a hard time juggling all of the demands of work, home, and caring for her baby. Her husband is helpful though has to work a lot.

After the assessment of orthostatics, Faith becomes lightheaded when standing. She was orthostatic for heart rate (>20 bpm) after 1, 3, and 5 minutes in standing. Her blood pressure also drops a bit in standing (<10 mmHg systolic) though was not considered orthostatic. She also has a Beighton score of 7 out of 9, has piezogenic papules on both of her heels, and soft velvety skin which is easily stretched.

Faith is asked if she would consider trying some salty snacks and some Gatorade to see if this helps with her lightheadedness. She responds that she will not eat pretzels or salty snacks because they are too high in carbs and she will not consider Gatorade because she doesn't drink beverages that are high in calories.

She keeps touching her abdomen and is uncomfortable about the “stretch marks'' that she has. She also keeps looking at herself in the mirror that is in the treatment room pulling her baggy sweater over her body.

She shares that she has always had constipation and abdominal pain - however this has really worsened lately. Faith also reports pelvic pressure at times and hopes that she does not have to deal with a pelvic organ prolapse like her mother had a few years ago.

During her first visit, she speaks very quickly and appears quite anxious.

This is only part of the history…but what might be helpful to say, do, explore, and assess?

_____________________________________________________________________

Brian

Brian is a 17-year-old wrestler who is coming to pelvic floor physical therapy for abdominal and pelvic pain. He shares that when he has to make "weight" before each meeting he will restrict water, and food and will exercise with layers of clothing on. He will drink about a cup of water during the day on those days and sometimes will just eat some chocolate, such as a peppermint patty, for dinner. After the meeting, he will sometimes eat a lot. He will often have significant abdominal pain and it will make him double over sometimes. He went to the GI doctor and was told that he has gastroparesis. He does not not know what he is supposed to do. If he doesn't eat, his abdomen hurts, and if he does eat it hurts too.

He also shares that he doesn't like school so much anymore. There is a lot of pressure to get a college scholarship and he is waiting to hear from a couple of his top choices. He doesn't feel like hanging out with some of his friends so much anymore. They always want to go out to eat and he can't do that. He typically will spend time with other wrestlers or will just stay at home. He reports being exhausted and having a hard time concentrating on his schoolwork.

Brian shares with you that he has to strain so much to have a bowel movement that he sometimes feels a bulging from his anus. He has a bowel movement about once a week and it is painful.

He does have urinary urgency and reports urinating "a little bit" many times during the day. His urine is tan in color.

When further questioned about Brian's response on the male genitourinary pain index (GUPI), he reports that he does not have pain with sexual climax because he does not have any desire to be sexually active anymore.

This is just a glimpse of Brian's journey... What other questions might you have? What can we do to help? What else would you be assessing?

_____________________________________________________________________

Joy

Joy is a 34-year-old musician with a history of binge eating disorder, which has been well-controlled for over five years. She comes to you with pelvic pain, dyspareunia, abdominal pain, and a history of constipation and urinary incontinence.

Joy saw a pelvic pain specialist who recommended a tricyclic antidepressant for pelvic pain. Joy also has bipolar disorder. She is in DBT treatment weekly (group and individual) and is well supported by her psychiatrist.

She is reporting new binge-related urges that are becoming hard to control since beginning the new medication. She is concerned about these new urges and this is causing additional anxiety. Her pelvic pain is actually worsening now with the additional anxiety and she is beginning to leak urine more frequently. Bowels are becoming firmer and harder to pass.

What are some next steps with Joy? What can we do to assist with her situation?

_____________________________________________________________________

Eating Disorders and Pelvic Health Rehabilitation: The Role of a Rehab Professional is a live remote course (including lab and lecture) with required seven-hour pre-course content accessible on Teachable. During the live course, there will be lectures, interactive discussions, and lab activities. We recommend, if possible, having another human available during the lab activities to practice the techniques discussed.

I look forward to seeing you on April 22!

Eating Disorders and Pelvic Health Rehabilitation

Course Dates: April 22

Price: $395

Experience Level: Beginner

Contact Hours: 13.25

Description: This course explores types of eating disorders including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, ARFID (Avoidant Restrictive Feeding Intake Disorder), and OSFED (Otherwise Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder). We will also discuss conditions that do not yet have formal diagnostic criteria such as orthorexia and diabulimia and we will touch on Pica and Rumination Disorders. Most healthcare professionals understand very little about eating disorders and disordered eating. There is a weight stigma with health care identifying “health” in terms of weight, BMI, body appearance, exercise, and activity. As rehabilitation professionals, it is our responsibility to understand that health looks and feels different for everyone. In addition, we may be able to identify signs and symptoms of eating disorders and be able to provide support for these individuals through proper referral and modification of our rehabilitation plan of care.