Concepts in "core" strengthening have been discussed ubiquitously, and clearly there is value in being accurate with a clinical treatment strategy, both for reasons of avoiding worsening of a dysfunctional movement or condition, and for engaging the patient in an appropriate rehabilitation activity. Because each patient presents with a unique clinical challenge, we do not (and may never) have reliable clinical protocols for trunk and pelvic rehabilitation. Rather, reliance upon excellent clinical reasoning skills combined with examination and evaluation, then intervention skills will remain paramount in providing valuable therapeutic approaches.

Even (and especially) for the therapist who is not interested in learning how to assess the pelvic floor muscles internally for purposes of diagnosis and treatment, how can an "external" approach to patient care be optimized to understand how the pelvic floor plays a role in core rehabilitation, and when does the patient need to be examined by a therapist who can provide internal examination and treatment if deemed necessary? There are many valuable continuing education pathways to address these questions, including courses offered by the Herman & Wallace Institute that instruct in concepts focusing on neuromotor coordination and learning based in clinical research.

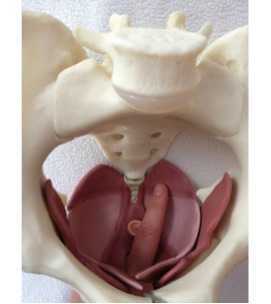

One article that helps us understand how the trunk can be affected by the pelvic floor was completed in 2002 by Critchley and describes how, in the quadruped position, activation of the pelvic floor muscles increased thickness in the transversus abdominis muscles. Subjects were instructed in a low abdominal hallowing maneuver while the transversus abdominis, obliquus internus, and obliquus externus muscle thickness was measured by ultrasound. While no significant changes were noted in obliques muscle thickness, transversus abdominis average measures increases from 49.71% to 65.81% when pelvic floor muscle contraction was added to the abdominal hollowing. Clinical research such as this helps us to understand how verbal cues and concurrent muscle activation may affect exercise prescription.

A collection of clinical research concepts such as the article by Critchley is valuable in connecting points of function and dysfunction for patients with trunk and pelvic conditions- a large part of many clinicians' caseloads. The Pelvic Floor Pelvic Girdle continuing education course instructs in foundational research concepts that tie together the orthopedic connections to the pelvic floor including lumbopelvic stability and mobility therapeutic exercises. Common conditions such as coccyx pain and other pelvic floor dysfunctions are instructed along with pelvic floor screening, use of surface EMG biofeedback, and risk factors for pelvic dysfunction. If you would like to pull together concepts in lumbopelvic stability with your current internal pelvic muscle skills, OR if you would like to attend this course to learn external approaches, you can sign up for the class that takes place in late September in Atlanta.

In a recent study examining demographic and obstetric factors on sleep experience of 202 postpartum mothers, researchers report that better sleep quality correlated negatively with increased time spent on household work, and correlated positively with a satisfactory childbirth experience. Let's get right to the take home points: how are we addressing postpartum birth experiences in the clinic, and how can we best educate new mothers in self-care? You will find many posts in the Herman Wallace blog about peripartum issues, and you can access the link here.

The authors recommend that healthcare providers "…should improve current protocols to help women better confront and manage childbirth-related pain, discomfort, and fear." Do you have current resources with which you can discuss these issues (and a referral to an appropriate provider) when needed? In our postpartum

course, we highlight the challenges a new mother faces due to the commonly-experienced fatigue in the postpartum period. According to Kurth et al., exhaustion impairs concentration, increases fear of harming the infant, and can trigger depressive symptoms. Issues of lack of support, not napping, overdoing activities,, worrying about the baby, and evenworrying about knowing you should be sleepingcan worsen fatigue in a new mother. (Runquist et al., 2007)

Back to what we can do for the patient: investigate local resources. This may include knowing what education is happening in local childbirth classes (and providing some training when possible respectfully inquiring of new mothers how they are doing with sleep and demands of running a household (and business or work life and finding out what support/resources the new mother has but is not accessing. Patients are often hesitant to ask for help, or may feel guilty in hiring someone to help clean for the first few months, feeling that she "should" be able to handle the chores and tasks. Educating women about results of the research and about potential improvements in quality of life can help the entire family.

If you are interested in learning more about Care of the Postpartum Patient, sign up today for our next continuing education course taking place next month in the Chicago area. (Don't you have a friend to visit in Chicago?) If you can't attend the Postpartum course, how about the Pregnancy and Postpartum Special Topics course taking place in October in Houston? Check the website as we add more Peripartum course series events, including Care of the Pregnant Patient, for 2015!

Insights in fascial mobility and dysfunctions are provided in this article by Gil Headley, and instructor who spends a significant amount of time working with anatomical dissections. Visceral fascia, according to Hedley, contains 3 layers: a fibrous outermost layer, a parietal serous layer, and a visceral serous layer. Fascial layers are, for the most part, designed to be able to slide over one another. Dysfunction can occur when there is a fixation in the connective tissues that prevents such sliding. A disruption in visceral fascial mobility may impair the necessary functional movement of the organs. Consider the mobility of the lungs and the heart when neuromuscular functions cause air or blood to expand and contract within the organ spaces. Bringing the concept to pelvic rehabilitation, what impairments are encountered when the bladder cannot easily fill or contract, or when movement of the bowels tugs on fascial restrictions? How are the tissues of the vaginal canal influenced by restrictions in tissues above, behind, or below the structure?

Examples of causes of adhesions may include (but not are limited to) inflammation from infections or disease, post-surgical scarring, dysfunctions caused by prior adhesion or limitation, and intentional therapeutic adhesions (think of a prolapse repair). While fibrous adhesions, once palpated, may be manually pulled apart, this is not the recommendation of the article author. Unfortunately, such an approach can result in further opportunity for inflammation and adhesions. One method of improving tissue mobility is to manually facilitate "…movement towards the normal range of motion of the fixed tissues with gentle traction…" timed with deep breathing. This technique may improve the ability of the organs and tissues to slide upon one another, and also may help in prevention of further movement restrictions. Would this type of intervention always require hands-on care? The author provides an example of a patient providing gentle traction by reaching to a pull-up bar, performing deep breathing and various trunk rotation positions following a thoracic surgery.

Visceral mobilization techniques may be a part of a patient's healing approach, and these techniques may be therapist-directed, patient-directed, or both. The Institute is pleased to offer two upcoming visceral mobilization continuing education courses next month instructed by faculty member Ramona Horton. Visceral Mobilization of the Reproductive System takes place in Boston, and Visceral Mobilization of the Urologic System is being hosted in Scottsdale.

What is the best reason to take a mindfulness or meditation course? Self-care! How many of us make choices in our daily lives that put our own health and wellness first? While we stay busy doing the important work of taking care of our patients, we can often forget to take care of ourselvs. Oftentimes, in addition to perhaps not learning to value self-care as we were growing up in our own families, we don't have strategies or the time-management skills to implement self-care. What is self-care? Self-care, as suggested by compassionfatigue.org, can include healthy lifestyle practices involving physical activity and healthy dietary habits, setting boundaries (saying "no"), having a healthy support system in place, organizing daily life to be proactive rather than reactive, reserving energy for worthy causes, and creating balance in life. (Check out this link for a prior blog post on compassion fatigue!)

The truth is, healthcare providers are stressed and burnout is common. So how does taking a course in mindfulness benefit the health care provider? Recent research including a university center based mindfulness-based stress reduction course was implemented with 93 providers including physicians, nurses, psychologists, and social workers. The training involved 8 weeks of 2.5 hour classes in addition to a seven hour retreat. Participants were instructed in mindfulness practices including a body scan, mindful movement, walking and sitting meditations, and were involved in discussions in how to apply mindfulness practices in the work setting. Outcomes included the Maslach Burnout Inventory and the SF-12. Results of the training, which was offered 11 times over a 6 year period, included improved scores relating to burnout and mental well-being.

But where can you take a course to learn valuable self-care tools? First up, there's the Meditation and Pain Neuroscience continuing education course happening at the beginning of next month. Then there is the Mindfulness-based Biopsychosocial Approach to the Treatment of Chronic Pain taking place in November in Seattle! Join us as we spread the word about how to not only take good care of your patients, but also of yourself.

In pelvic rehab, if you ask therapists from around the country, you will most often hear that patients with pelvic dysfunction are seen once per week. This is in contrast to many other physical therapy plans of care, so what gives? Perhaps one of the things to consider is that most patients of pelvic rehab are not seen in the acute stages of their condition, whether the condition is perineal pain, constipation, tailbone pain, or incontinence, for example.

The literature is rich with evidence supporting the facts that physicians are unaware of, unprepared for, or uncomfortable with conversations about treatment planning for patients who have continence issues or pelvic pain. The research also tells us that patients don't bring up pelvic dysfunctions, due to lack of awareness for available treatment, or due to embarrassment, or due to being told that their dysfunction is "normal" after having a baby or as a result of aging. So between the providers not talking about, and patients not bringing up pelvic dysfunctions, we have a huge population of patients who are not accessing timely care.

What else is it about pelvic rehab that therapists are scheduling patients once a week? Is it that the patient is driving a great distance for care because there are not enough of us to go around? Do the pelvic floor muscles have differing principles for recovery in relation to basic strengthening concepts? Or is the reduced frequency per week influenced by the fact that many patients are instructed in behavioral strategies that may take a bit of time to re-train?

Pelvic rehabilitation providers are oftentimes concerned about the plans of care (POC) being once per week not because patients always need more visits, but because insurance providers are accustomed to seeing a POC with ranges of 2-3 visits per week, and in some cases, even 4-7 visits per week, based upon diagnosis, facility, and patient needs. To justify and support our once per week POC, we need only look to research protocols, to clinical care guidelines, and to clinical recommendations and practice patterns of our peers. For the following conditions, most of the cited research uses a once per week (or less) protocol or guideline:

Braekken et al., 2010: randomized, controlled trial with once per week visits for first 3 months, then every other week for last 3 months.

Croffie et al., 2005: 5 visits total, scheduled every 2 weeks.

Fantl & Newman, 1996: Meta-analysis of treatment for urinary incontinence, recommends weekly visits.

Fitzgerald et al., 2009: Up to 10 weekly treatments (1 hour in duration) was used in the largest randomized, controlled trial of chronic pelvic pain.

Hagen et al., 2009: Randomized, controlled trial using an initial training class, followed by 5 visits over a 12 week period.

Terra et al., 2006: Protocol used 1x/week for 9 weeks.

Weiss, 2001: 1-2 visits per week for 8-12 weeks.

Vesna et al., 2011: Children were randomized into 2 treatment groups with 1 session per month for the 12 month treatment period.

While not every patient is seen once per week in pelvic rehabilitation, Herman & Wallace faculty can tell you that once a week is the most common practice pattern observed for urinary dysfunction, prolapse, and pelvic pain. Certainly, a patient with an acute injury, a need for expedited care (limited insurance benefits, goals related to upcoming return to work or travel plans, or insurance expectations that dictate plan of care) may lead to frequency of visits that are more than once per week.

If you are interested in learning more about treatment care plans for a variety of pelvic dysfunctions, sign up for one of the pelvic series courses, and for special populations such as pediatrics, check out the Pediatric Incontinence continuing education course taking place in South Carolina at the end of this month!

References

Braekken, I. H., Majida, M., Engh, M. E., & Bo, K. (2010). Can pelvic floor muscle training reverse pelvic organ prolapse and reduce prolapse symptoms? An assessor-blinded, randominzed, controlled trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 203(2), 170.e171-170.e177. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.037

Croffie, J. M., Ammar, M. S., Pfefferkorn, M. D., Horn, D., Klipsch, A., Fitzgerald, J. F., . . . Corkins, M. R. (2005). Assessment of the effectiveness of biofeedback in children with dyssynergic defecation and recalcitrant constipation/encopresis: does home biofeedback improve long-term outcomes. Clinical pediatrics, 44(1), 63-71.

Fantl, J., & Newman, D. (1996). Urinary incontinence in adults: Acute and chronic management. Rockville, MD: AHCPR Publications.

FitzGerald, M. P., Anderson, R. U., Potts, J., Payne, C. K., Peters, K. M., Clemens, J. Q., . . . Nyberg, L. M. (2009). Adult Urology: Randomized Multicenter Feasibility Trial of Myofascial Physical Therapy for the Treatment of Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndromes. [Article]. The Journal of Urology, 182, 570-580. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.022

Hagen, S., Stark, D., Glazener, C., Sinclair, L., & Ramsay, I. (2009). A randomized controlled trial of pelvic floor muscle training for stages I and II pelvic organ prolapse. International Urogynecology Journal, 20(1), 45-51. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0726-4

Terra, M. P., Dobben, A. C., Berghmans, B., Deutekom, M., Baeten, C. G. M. I., Janssen, L. W. M., ... & Stoker, J. (2006). Electrical stimulation and pelvic floor muscle training with biofeedback in patients with fecal incontinence: a cohort study of 281 patients. Diseases of the colon & rectum, 49(8), 1149-1159.

Weiss, J. M. (2001). Clinical urology: Original Articles: Pelvic floor myofascial trigger points: manual therapy for interstitial cystitis and the urgency-frequency syndrome. . [Article]. The Journal of Urology, 166, 2226-2231. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65539-5

Vesna, Z. D., Milica, L., Stankovi?, I., Marina, V., & Andjelka, S. (2011). The evaluation of combined standard urotherapy, abdominal and pelvic floor retraining in children with dysfunctional voiding. Journal of pediatric urology, 7(3), 336-341.

George Thiele, MD, published several articles relating to coccyx pain as early as 1930 and into the late 1960's. His work on coccyx pain and treatment remains relevant today, and all pelvic rehabilitation providers can benefit from knowledge of his publications. Thiele's massage is a particular method of massage to the posterior pelvic floor muscles including the coccygeus. Dr. Thiele, in his article on the cause and treatment of coccygodynia in 1963, states that the levator ani and coccygeus muscles are tender and spastic, while the tip of the coccyx is not usually tender in patients who complain of tailbone pain. The same article takes the reader through an amazing literature review describing interventions for coccyx pain in the early 20th century.

Examination and physical findings, according to Dr. Thiele, include slow and careful sitting with weight often shifted to one buttock, and frequent change of position. He also describes poor sitting posture, with pressure placed upon the middle buttocks, sacrum, and tailbone. Postural dysfunction as a proposed etiology is not a new theory, and in Thiele's article he states that poor sitting posture is "…the most important traumatic factor in coccygodynia…" and even referred to postural cases as having "television disease."

In reference to treatment, Thiele suggests putting a patient in Sims' position (left lateral side lying or recumbent position), and placing the gloved index finger into the rectum with the thumb over the coccyx externally, palpating the coccyx between the thumb and index finger. The finger is then moved laterally, in contact with the soft tissues of the coccygeus, levator ani, and gluteus maximus muscles. The finger is moved with moderate pressure "…laterally, anteriorly, and then medially, describing an arc of 180 degrees until the finger tip lies just posterior to the symphysis pubis." The massaging strokes, applied to a patient's tolerance, are applied 10-15 repetitions on each side with the patient being asked to bear down during the massage strokes. Dr. Thiele recommended daily massage 5-6 days, then every other day for 7-10 days, and gradually less often until symptoms are resolved.

Thiele's massage for coccygodynia is one excellent tool in the treatment of coccyx pain. For a comprehensive view of coccyx pain, check out faculty member Lila Abatte's Coccyx Pain Evaluation and Treatment continuing education course, coming up in New Hampshire in September!

Posttraumatic Stress Syndrome, also known as PTSD, is an unfortunate consequence of many women's birth experiences. While there are known risk factors, there is not currently a standardized screening method for identifying symptoms of PTSD in the postpartum period. One recent meta-analysis of 78 research studies identified a prevalence of postpartum PTSD as 3.1% in community samples and as 15.7% in at-risk or targeted samples. Risk factors for PTSD included current depression, labor experiences (including interactions with medical staff), and a history of psychopathology. In the targeted samples, risk factors included current depression and infant complications. Other authors have explored the relationships between preterm birth and PTSD, preeclampsia or premature rupture of membranes, and infants in the neonatal intensive care unit.

One of the main concerns of failing to identify and treat for PTSD in the postpartum period is the potential negative effect on the family. High levels of anxiety, stress, and depression may impact not only the mother's health, but also may affect her ability to meet her new infant's needs, or complete usual functions in work and home life. One study suggested that "…maternal stress and depression are related to infants’ ability to self-sooth during a stressful situation." Clearly, healthy moms promote healthy families, and each mother deserves the attention that her new infant often receives from the world!

How can we be a part of the solution? We have previously posted on the blog about screening for depression in the postpartum period. The US Department of Veterans Affairs lists multiple screening tools for PTSD as well. Here's another bit of exciting news: yoga has been identified as a method to reduce symptoms of PTSD. In a randomized, controlled clinical trial, the treatment arm was given 10 weeks (1x/week at 1 hour sessions) of "trauma-informed" yoga, whereas the control group was given information about women's health and self-efficacy in various domains. Interestingly, while both groups showed positive effects from intervention in the first half of the treatment, the yoga group maintained the improvements during the latter half of the study, while the control group relapsed.

You can learn about yoga for postpartum mothers, and learn how to integrate strategies to help heal postpartum symptoms of PTSD this summer at Ginger Garner's Yoga as Medicine for Labor & Delivery and Postpartum. The continuing education course takes place in Seattle, and we still have a few spots left! Don't miss this chance to add more amazing tools to your toolbox in support of women of any postpartum age.

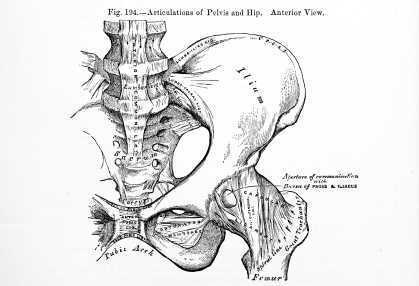

While many of the Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation continuing education courses focus on study of the pelvic floor muscles, the inclusion and consideration of the trunk, breathing, form and force closure, and posture are also needed to truly understand the pelvis. Our professional education does not prepare us well in regards to understanding the pelvic floor and pelvic girdle, and the foundational concepts that provide clinical meaningfulness come from a variety of research camps. If you feel that you were never provided this foundational information about the pelvic girdle and trunk, and wish to better apply practical concepts in movement and muscle facilitation (or inhibition), you might be looking for the Pelvic Floor/Pelvic Girdle continuing education course that is coming to Atlanta in late September.

The course covers interesting topics such as pelvic floor muscle activation patterns in health and in dysfunction, use of load transfer tests such as the active straight leg raise, orthopedic considerations of pelvic dysfunction, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) exercise cues, risk factors for pelvic dysfunction, and treatment of the coccyx. If you (or a friend you want to take a course with) is not quite sure about internal pelvic floor coursework at this time, the good news is that this course addresses pelvic dysfunction using an external approach. Experienced therapists can appreciate the research-based approach to muscle dysfunctions that can cause or perpetuate a variety of symptoms, and newer therapists have the chance to learn how to integrate pelvic floor/pelvic girdle concepts into current practice. A biofeedback lab introduces use of surface electromyography (sEMG) as well.

There is still time to sign up for the September course in Atlanta, the only remaining opportunity to take the Pelvic Floor/Pelvic Girdle continuing education course this year. Bring a friend, or a colleague, and work together to combine external and internal approaches to pelvic dysfunction.

In this study investigators tested the hypothesis that following hip arthroscopy, the number of patients who developed pudendal neuralgia would exceed 1%. Development of pudendal neuralgia symptoms following hip arthroscopy was assessed in 150 patients (female = 79, male = 71) who were operated on in one facility by a single surgeon. Indications for the surgery included post-trauma foreign-body, osteochondromatosis, and labral lesion resection. The Nantes criteria were utilized for diagnosis, which includes as "essential" criteria the following: pain in the region of the pudendal nerve; pain that is worsened by sitting, relieved by sitting on a toilet seat; pain does not interrupt sleep, pain with no objective sensory impairment and that is relieved by a pudendal nerve block.

The operated hip was placed in a position of 30 degrees of adduction, internal rotation and flexion. The hip was operated on with a single anterolateral approach in most cases, with a second anterolateral approach needed in eight cases. Study results include an incidence rate of 2% in the population of 150 patients. 3 of the patients (2 female, 1 male) were diagnosed with pudendal neuralgia presenting in all 3 as "pure sensory" with symptoms of perineal hypoesthesia and dysesthesia on the operated side. The 3 cases resolved spontaneously within 3 weeks to 6 months. Two cases of sciatica following hip arthroscopy were documented, and these cases resolved without intervention other than a short course of analgesics. The patients also presented with gluteus medius insertion tenderness.

Although the study also aimed to determine risk factors for development of pudendal neuralgia following hip scope, the small number of patients who developed symptoms made the analysis for risk factors difficult. The authors also point out that the one-way surgical technique (not the standard surgical technique) also may have created some bias in the study. In conclusion, although the cited study reported a low incidence of pudendal neuralgia onset following hip arthroscopy, larger numbers have appeared in the literature, and according to the authors, surgical risk factors for developing nerve complications following a hip scope include the amount of traction placed on the joint, the length of surgery, and appropriate pelvic support bilaterally. The take-home point for pelvic rehabilitation providers is that patients are at some risk for pelvic nerve dysfunction following hip arthroscopy, and we have a role in educating providers and in screening patients for such conditions.

The Herman & Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute offers many relevant courses regarding the hip and pelvis, and if you are interested in learning more about the pudendal nerve, hurry to sign up for the continuing education course "Pudendal Neuralgia Assessment, Treatment, and Differentials." You can also attend "Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis" continuing education course to learn all about testing, treatment, and diagnosis of the hip and pelvis.

This post was written by H&W instructor Steve Dischiavi, MPT, DPT, ATC, COMT, CSCS. Dr. Dischiavi will be instructing the course that he wrote on "Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip and Pelvis" in Virginia this August.

In an outpatient sports medicine clinic the traditional model of physical therapy evaluation typically includes the therapist reviewing a patients chart and subjective symptom questionnaire of some sort. Then the therapist will bring the patient to an area to begin a subjective history and then onto a physical exam. After these procedures have been completed the therapist will typically assign a working clinical diagnosis and then begin treatment. In short, I would like to suggest a paradigm shift to this traditional model of thinking. Instead of starting the exam on a table with a static assessment of the structures involved and identifying the pain generator, I suggest the therapist begin with a specific set of movements used as an evaluative tool to identify movement dysfunction within the anatomical system as a whole.

All human interactions on earth occur between ground reaction force and gravity, our bodies are mostly just stuck in the middle of this constant battle and typically we succumb to whichever power exposes the weakest link in our biomechanical chains. One of the reasons the biomechanical chains in our bodies are so pliable and vulnerable to constant ground reaction force and gravity acting on them is because we are basically bones or struts suspended in a bag of skin all connected by soft tissue. Suggesting that without skin, fascia, and connective tissue supporting us, we would collapse to the ground in a pile of bones! Ingber (1997), suggested this concept, known as tensegrity, was the “architecture of life.” So in summary, the tensegrity structures are mechanically stable not because of the strength of the individual bones, but because of the way the entire human body distributes and balances mechanical stresses through the use of polyarticular muscle chains called slings. There will be more on slings in the upcoming blogs.

If there is truly a paradigm shift with the way we initially assess our clients and we begin our evaluations with whole system movement patterns it would be because we want to actually see how this tensgerity model is essentially collapsing under the stress of gravity. We would get a first hand glimpse in real time how energy leaks and blocks occur during human movement. These concepts are the foundation for the course Biomechanical Assessment of the Hip & Pelvis.

Ingber, D.E. (1997). Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction.

Annual Review of Physiology, 59, 575-59.

Dr. Dischiavi's course is designed to elevate the participant’s skill level through advanced training in hip and pelvic biomechanics, functional “slings” created by the myofascial system, and through use of sports medicine theory and applied science. Biomechanical Assessment of The Hip & Pelvis will be taking place in August in Arlington, VA

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://www.hermanwallace.com/