“However, at present we are all aglow with views on visceral anatomy and medical colleges are wisely establishing chairs in this department which will result in much advancement.” -Fred Byron Robinson, 1891 (Cysts of the Urachus)

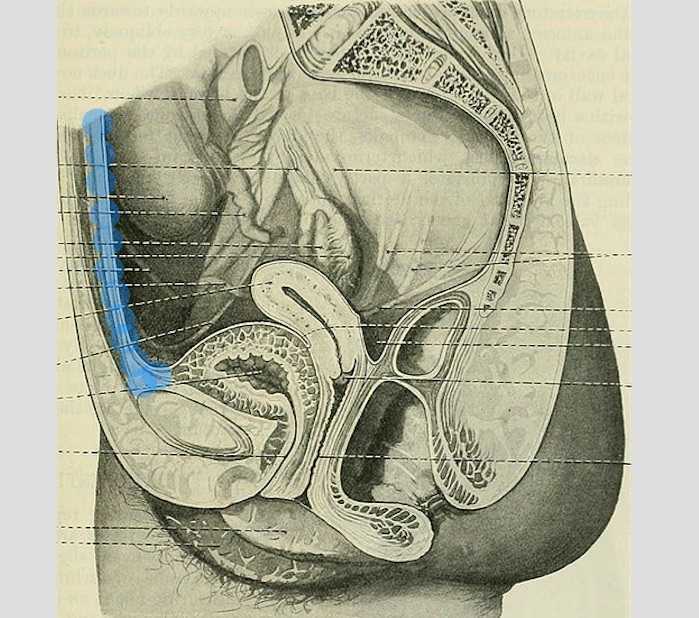

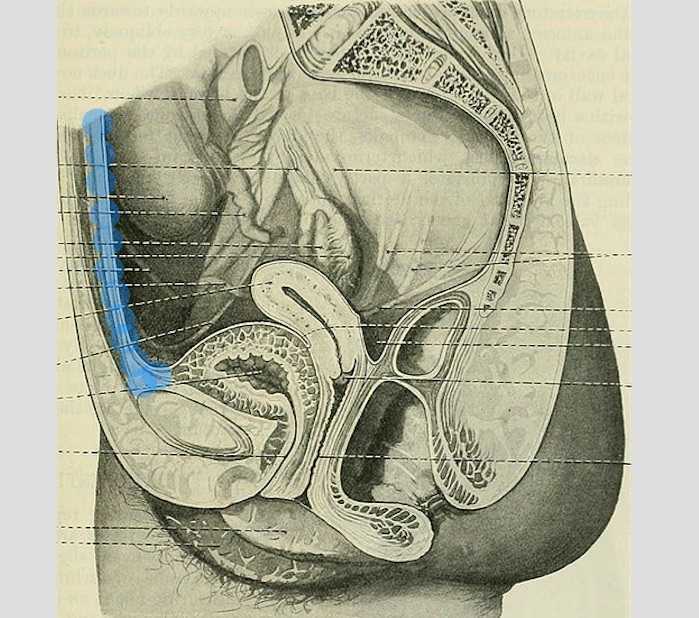

The above (fabulous) quote reminds us that many came before us who were equally excited by the study of anatomy. One anatomical structure that I know never appeared in my graduate anatomy courses is the urachus. The urachus is a structure that extends from the urinary bladder to the umbilicus (highlighted blue in the image). When investigating literature about this structure I was impressed to find publications about the urachus dating from the late 19th century.

It wasn’t until several years into my career as a physical therapist that I learned about the urachus, a structure attached to the bladder, and learned how this structure could create some rather dramatic symptoms when in dysfunction. I met a woman who was in her early 30’s and who had 6 months prior undergone a laparoscopic surgery with access just below the umbilicus. She presented to rehabilitation after seeing an urologist for severe pain that occurred towards the end of voiding. The pain was absent at any other time, but was so severe towards the latter half of emptying her bladder that she would double over in pain and “nearly pass out.” Investigation revealed a healthy, well-functioning pelvic floor and abdominal wall, but a reproduction of her severe pain with palpation to the midline between the umbilicus and the pubic bone. After grabbing some anatomy texts, I supposed that the urachus, having potentially been irritated by the laparoscopic approach, might experience a tensioning of the irritated tissue as the bladder contracted to empty. This theory appeared to hold some weight, as applying gentle manual therapy to the tissues, and teaching the patient some self-release techniques allowed her to resolve her symptoms entirely after 1-2 visits.

The urachus is formed in early development from the pre-peritoneal layer, and is described as vestigial tissue. It extends from the anterior dome of the bladder to the umbilicus, varying in length from 3-10 cm, with a diameter of 8-10 mm. There are 3 layers: an inner layer of transitional or cuboid epithelial cells surrounded by a layer of connective tissue. The remains of the urachus form the middle umbilical ligament which is a fibromuscular cord. A layer of smooth muscle that is continuous with the detrusor (smooth muscle of the bladder) makes up the outer layer. This continuity of tissue may help explain some of the clinical connections we see in patient symptoms. In the past year, I have met several patients for whom the urachus is the only tissue that reproduced their symptoms. I examined a male patient who reported urethral burning that occurred with both reset and activity. Unable to produce symptoms in any other location of the thoracolumbar spine, pelvic floor and walls, or abdomen, I palpated this structure to find that it reproduced the urethral burning. Another patient presented with a keloid c-section scar. She also described a sharp pain when the bladder was full. Treatment directed to the scar and along the midline resolved this pain, again with a couple sessions.

If you are interested in learning more about distinct anatomical connections that can help you explain (and treat) issues your patients present with, come and learn with us at the 3-day Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, and Treatment course offered four times over the 2019 and 2020 calendars. The role of the urachus in abdominopelvic dysfunction is just one of the many topics we explore. With lectures on sexual health, pelvic pain, prostate and urinary dysfunction, there is a broad range of topics and skills to offer for clinicians who are new to men’s heath and those who have been treating for years.

Begg, R. C. (1930). The Urachus: its Anatomy, Histology and Development. Journal of Anatomy, 64(Pt 2), 170–183.

Gray, H. (1918). Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Sterling, J. A., & Goldsmith, R. (1953). Lesions of Urachus which Appear in the Adult. Annals of Surgery, 137(1), 120–128.

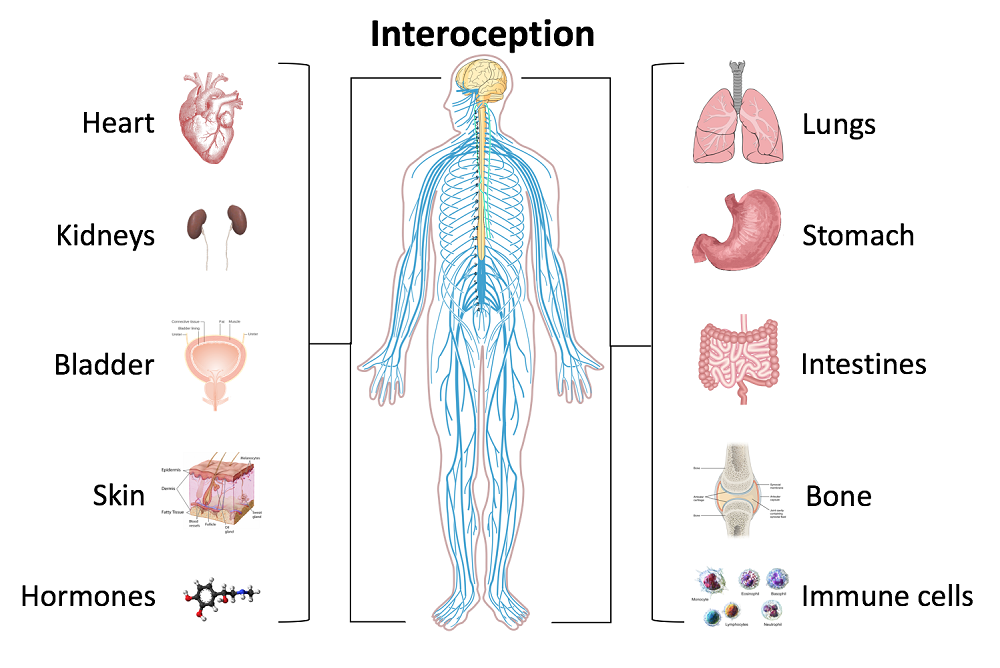

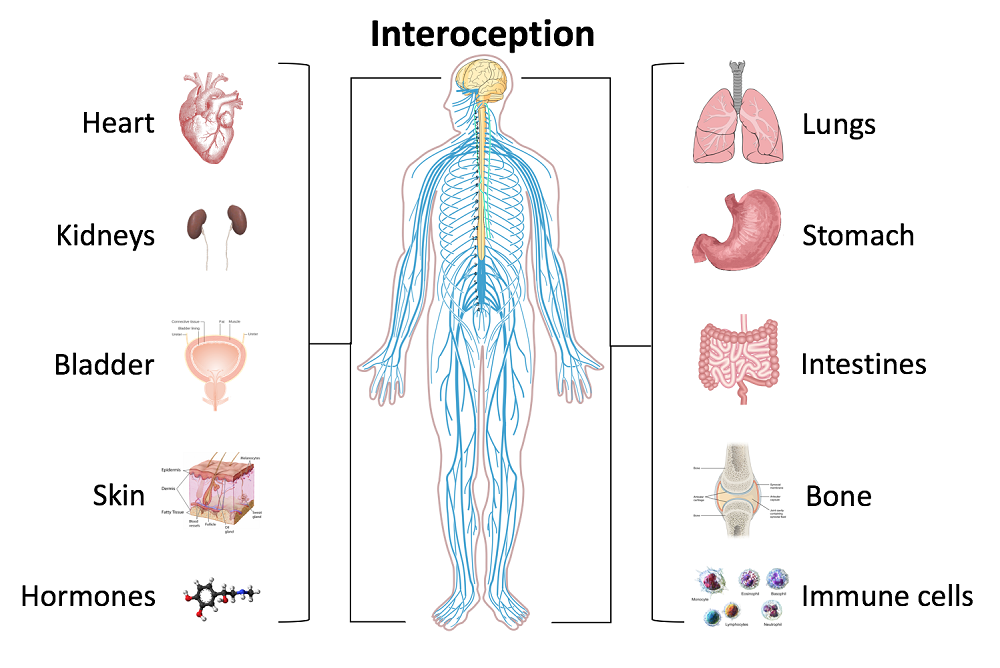

In an effort to provide the best possible educational experience for clinical rehabilitation application of neuroanatomy, I was on a mission. Having a core, base knowledge review of the nervous system is essential when leading into talking about dysfunction and disease of that system. I went on a search for anatomical depictions that could clearly identify the structures and processes I was trying to portray. New books from the library and books I own from when I was in college serve as great resources when trying to get back into studying the specifics, but do not offer the opportunity to easily get these images into a powerpoint. Online resources are also challenging. I am learning how time consuming the process can be to determine who owns the online image, if it is free to copy, save and utilize for my own teaching purposes, or if I need to go through the process of requesting permissions for use.

Through my employer, where I treat patients in the clinic, I have access to a program called Primal Pictures. I had used this in the past for clinic related marketing presentations and educational materials for patients and other clinicians I have mentored. Looking into the product further, I came to find out that there is a newer version of the program which offered so many more options. A truly unlimited amount of images which can be manipulated into an optimal position depicting the most clear neuroanatomical views I have ever been able to find. Not only does it provide me with the images I need in order to depict the treacherous pathways of the nerves in our body, but it also provides some amazing depictions of the physiological processes that occur within our nervous system to allow for healthy day to day functioning and protection of our bodies.

I also came across the title of a journal article that I was sure would provide some excellent depictions of neuroanatomy. The article titled, Sectional Neuroanatomy of the Pelvic Floor, provides cross sectional views of both the male and female pelvises. I obtained the article which has an excellent color-coded system, each nerve colored the same as the muscles and skin surface it innervates, going from superior to inferior cross sections. This makes for a clear understanding of each structures anatomical position. It is a great reference when looking at the anatomical relationships to adjacent structures and can help guide palpation skills. The article was more specifically written for physicians to best direct needle procedures/injections in the most accurate location possible when targeting nerves and structures. Neuroanatomy and physiology can be essential to understanding certain patient populations we encounter as we practice pelvic floor rehabilitation. Having clear depictions to refer to can help you provide the best possible base knowledge to your patients as you help them understand the challenges they face and how to overcome them.

Kass, J. S., Chiou-Tan, F. Y., Harrell, J. S., Zhang, H., & Taber, K. H. (2010). Sectional neuroanatomy of the pelvic floor. Journal of computer assisted tomography, 34(3), 473-477.

Pain with sitting is a common complaint that patients may present to the clinic with. While excess sitting has been shown to be detrimental to the human body, sitting is part of our everyday culture ranging from sitting at a meal, traveling in the car, or doing work at a desk. Often, physical therapists disregard the coccyx or tailbone as the possible pain generator, simply because they are fearful of assessing it, have no idea where it is, or have never learned about it being a pain generator in their education.

Coccydynia is the general term for “pain over the coccyx.” Patients with coccydynia will complain of pain with sitting or transitioning from sit to stand. Despite the coccyx being such a small bone at the end of the spine, it serves as a large attachment site for many important structures of interest that are important in pelvic floor support and continence: ¹

- Anterior: Levator ani muscles, Sacrococcygeal ligament

- Lateral: Coccygeal muscles, Sacrospinous ligament, Sacrotuberous ligament, Glute maximus muscle fibers

- Inferiorly: Iliococcygeus

Along with serving as a major attachment site for the above structures it provides a support for weightbaring in the seated position and provides structural support for the anus. Women are five times more likely to develop coccydynia than men, with the most common cause being an external trauma like a fall, or an internal trauma like a difficult childbirth. 1,2 In a study of 57 women suffering from postpartum coccydynia, most deliveries that resulting in coccyx pain were from use of instruments such as a forceps delivery or vacuum assisted delivery. A BMI over 27 and having greater than or equal to 2 vaginal deliveries resulted in a higher rate of coccyx luxation during birth. ³ Other causes of coccyx pain can be non traumatic such as rapid weight loss leading to loss of cushioning in sitting, hypermobility or hypomobility of the sacrococcygeal joint, infections like a pilonidal cyst, or pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. ¹ When assessing a patient with coccyx pain, it is also of the upmost importance to rule out red flags, as there are multiple cases cited in the literature of tumors such as retrorectal tumors or cysts being the cause of coccyx pain. These masses must be examined by a doctor to determine if they are malignant or benign, and if excision is necessary. Sometimes these masses can be felt as a bulge on rectal examination. 4,5

Along with serving as a major attachment site for the above structures it provides a support for weightbaring in the seated position and provides structural support for the anus. Women are five times more likely to develop coccydynia than men, with the most common cause being an external trauma like a fall, or an internal trauma like a difficult childbirth. 1,2 In a study of 57 women suffering from postpartum coccydynia, most deliveries that resulting in coccyx pain were from use of instruments such as a forceps delivery or vacuum assisted delivery. A BMI over 27 and having greater than or equal to 2 vaginal deliveries resulted in a higher rate of coccyx luxation during birth. ³ Other causes of coccyx pain can be non traumatic such as rapid weight loss leading to loss of cushioning in sitting, hypermobility or hypomobility of the sacrococcygeal joint, infections like a pilonidal cyst, or pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. ¹ When assessing a patient with coccyx pain, it is also of the upmost importance to rule out red flags, as there are multiple cases cited in the literature of tumors such as retrorectal tumors or cysts being the cause of coccyx pain. These masses must be examined by a doctor to determine if they are malignant or benign, and if excision is necessary. Sometimes these masses can be felt as a bulge on rectal examination. 4,5

A multidisciplinary approach including physical therapy, ergonomic adaptations, medications, injections, and, possibly, psychotherapy leads to the greatest chance of success in patients with prolonged coccyx pain. 1 Special wedge shaped sitting cushions can provide relief for patients in sitting and help return them to their social activities during treatment. Physical therapy includes manual manipulation and internal work to the pelvic floor muscles to alleviate internal spasms and ligament pain. Intrarectal coccyx manipulation can potentially realign a dislocated sacrococcygeal joint or coccyx. 1 Taping methods can be used as a follow up to coccyx manipulation to help hold the coccyx in the new position and allow for optimal healing. Often coccyx pain patients have concomitant pathologies such as pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, sacroilliac or lumbar spine pain, and various other orthopedic findings that are beneficial to address. When conservative treatments fail, injections or a possible coccygectomy may be considered.

Luckily conservative treatment is successful in about 90% of cases. ¹ All of the above conservative tools will be taught in the upcoming Coccyx Pain Evaluation and Treatment course on April 23-24th, 2016 in Columbia, MO taught by Lila Abbate PT, DPT, OCS, WCS, PRPC. By learning how to treat coccyx pain appropriately, you will be a key provider in solving many unresolved sitting pain cases that are not resolved with traditional orthopedic physical therapy.

1. Lirette L, Chaiban G, Tolba R, et al. Coccydynia: An overview of the anatomy, etiology, and treatment of coccyx pain. The Ochsner Journal. 2014; 14:84-87.

2. Marinko L, Pecci M. Clinical Decision Making for the Evaluation and Management of Coccydynia: 2 Case Reports. JOSPT. 2014; 44(8): 615

3. Maigne JY, Rusakiewicz F, Diouf M. Postpartum coccydynia: a case series study of 57 women. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012; 48 (3): 387-392.

4. Levine R, Qu Z, Wasvary H. Retrorectal Teratoma. A rare cause of pain in the tailbone. Indian J Surg. 2013; 75(2): 147-148.

5. Suhani K, Ali S, Aggarwal L, et al. Retrorectal cystic hamartoma: A problematic tail. J Surg Tech Case Rep. 2104; 6(2): 56-60.