Did you know that September is prostate cancer awareness month? As of 2020, prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men worldwide. Prostate cancer accounts for one in every 14 cancer diagnoses globally, and 15% of all cancers in patients born with a prostate. It ranks second in terms of cancer mortality in this population, second only to lung cancer.(1) A recent Lancet Commission on prostate cancer is projecting a significant increase in the number of new cases of prostate cancer annually. They are projecting that the number of new cases will rise from 1.4 million annually worldwide in 2020 to 2.9 million by 2040. This is due to changing age structures within the population and improved life expectancy.(1) This projected rise in prostate cancer cannot be prevented by lifestyle changes or public health interventions. Due to this projected increase in new cases, screening is a must and will be critical to better prognosis and survival for these patients. Along with a rise in prostate cancer, it is expected that other conditions such as diabetes and heart disease will mirror the projected increase in prostate cancer. It is recommended that screening and early diagnosis programs should not only focus on prostate cancer but “men’s health more broadly.”(1)

The Commission also recommended outreach programs to educate the population about prostate cancer. Social media and traditional media were both recommended to be used to reach individuals who may not be accessing medical care as frequently. This is something that we as rehabilitation clinicians can help with! As a rehabilitation clinician, we are expert educators for our patients. So much of what we do with patients is educate them about their bodies and things that can be done to assist in healing. We can take it a step further and educate them to have general health checks that would include screening for prostate cancer, among other screens such as for heart disease, and diabetes. We may also be able to reach other individuals by educating our patients to encourage their family and friends about the importance of general health screens. Many of us are also very adept at using social media to reach the community. Can we post something about Prostate Cancer Awareness Month? How easy is it to post a quick word about the expected rise in prostate cancer diagnoses and encourage patients to see their doctor for their annual health exam? Let’s all try to reach a few additional individuals this month in honor of Prostate Cancer Awareness Month! If we each are able to get a few more individuals in for screening, what impact could we make? This is something we should continue to do over the next several decades to encourage our patients to health screens! Mark your calendars every September to honor this month and educate our patients and their families!

To learn more about prostate cancer and how to treat this population, take Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Level 2A. This is an online course where you can learn specific techniques to help patients who have been diagnosed with pelvic cancers and colorectal cancers. It is offered September 7-8. Register today!

Reference:

- James N, Tannock I, N’Dow J, et al. (2024). The Lancet Commission on prostate cancer: planning for the surge in cases. The Lancet Commissions. 403(10437): P1683-1722. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/

S0140-6736(24)00651-2

AUTHOR BIO:

Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, BCB-PMD, PRPC

Allison Ariail has been a physical therapist since 1999. She graduated with a BS in physical therapy from the University of Florida and earned a Doctor of Physical Therapy from Boston University in 2007. Also in 2007, Dr. Ariail qualified as a Certified Lymphatic Therapist. She became board-certified by the Lymphology Association of North America in 2011 and board-certified in Biofeedback Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction by the Biofeedback Certification International Alliance in 2012. In 2014, Allison earned her board certification as a Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner. Allison specializes in the treatment of the pelvic ring and back using manual therapy and ultrasound imaging for instruction in a stabilization program. She also specializes in women’s and men’s health including conditions of chronic pelvic pain, bowel and bladder disorders, and coccyx pain. Lastly, Allison has a passion for helping oncology patients, particularly gynecological, urological, and head and neck cancer patients.

Allison Ariail has been a physical therapist since 1999. She graduated with a BS in physical therapy from the University of Florida and earned a Doctor of Physical Therapy from Boston University in 2007. Also in 2007, Dr. Ariail qualified as a Certified Lymphatic Therapist. She became board-certified by the Lymphology Association of North America in 2011 and board-certified in Biofeedback Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction by the Biofeedback Certification International Alliance in 2012. In 2014, Allison earned her board certification as a Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner. Allison specializes in the treatment of the pelvic ring and back using manual therapy and ultrasound imaging for instruction in a stabilization program. She also specializes in women’s and men’s health including conditions of chronic pelvic pain, bowel and bladder disorders, and coccyx pain. Lastly, Allison has a passion for helping oncology patients, particularly gynecological, urological, and head and neck cancer patients.

In 2009, Allison collaborated with the Primal Pictures team for the release of the Pelvic Floor Disorders program. Allison's publications include: “The Use of Transabdominal Ultrasound Imaging in Retraining the Pelvic-Floor Muscles of a Woman Postpartum.” Physical Therapy. Vol. 88, No. 10, October 2008, pp 1208-1217. (PMID: 18772276), “Beyond the Abstract” for Urotoday.com in October 2008, “Posters to Go” from APTA combined section meeting poster presentation in February 2009 and 2013. In 2016, Allison co-authored a chapter in “Healing in Urology: Clinical Guidebook to Herbal and Alternative Therapies.”

Allison works in the Denver metro area in her practice, Inspire Physical Therapy and Wellness, where she works in a more holistic setting than traditional therapy clinics. In addition to instructing Herman and Wallace on pelvic floor-related topics, Allison lectures nationally on lymphedema, cancer-related changes to the pelvic floor, and the sacroiliac joint. Allison serves as a consultant to medical companies, and physicians.

Outside of work, Allison enjoys spending time with her family, caring for her animals, reading, traveling, and most importantly of all, being a mom! She lives in the Denver metro area with her family.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a debilitation complication of radical prostatectomy, which is a treatment for prostate cancer. ED is caused by a variety of causes, diabetic vasculopathy, smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, psychological issues, peripheral vascular disease and medication; we will focus on post-prostatectomy ED and the role of penile rehabilitation in its management.

Post-prostatectomy-related Erectile dysfunction

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Radical prostatectomy can result in nerve injury to the penis. Moreover, significant fibrotic changes take place in the corpus cavernosum of the penis postoperatively. It takes approximately 1-2 years for erectile function to return after radical prostatectomy. This is a period of “neuropraxia,” during which there is transient cavernosal nerve dysfunction. However, a prolonged “flaccid state” might lead to irreversible damage to the cavernous tissue 1.

Research on penile hemodynamics in these patients have shown that venous leakage is also implicated in its pathophysiology. An injury to the neurovascular bundles likely leads to smooth muscle cell death, which then leads to irreversible veno-occlusive disease.

There is a potential role of hypoxia in stimulating growth factors (TGF-beta) that stimulate collagen synthesis in cavernosal smooth muscle. Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) was found to suppress the effect of TGF-β1 on collagen synthesis.

Role of Penile Rehabilitation

The goal of Penile Rehabilitation is to limit and reverse ED in post-prostatectomy patients. The idea is to minimize fibrotic changes during the period of “penile quiescence” after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Several approaches have been tried, including PGE1 injection, vacuum devices, and phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors.

Mulhall and coworkers followed 132 patients through an 18-month period after they were placed in “rehabilitation” or “no rehabilitation” groups after radical prostatectomy, and 52% of those undergoing rehabilitation (sildenafil + alprostadil) reported spontaneous functional erections, compared with 19% of the men in the no-rehabilitation group 2.

Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1)

Alprostadil is a vasodilatory prostaglandin E1 that can be injected into the penis or placement in the urethra in order to treat ED. Montorsi, et al. studied the use of intracorporeal injections of alprostadil starting at 1 month after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and reported a higher rate of spontaneous erections after 6 months compared with no treatment 3. Gontero, et al. investigated alprostadil injections at various time points after non–nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy and found that 70% of patients receiving injections within the first 3 months were able to achieve erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 40% of patients receiving injections after the first 3 months 4.

Vacuum constriction device (VCD)

VCD is an external pump that is used to get and maintain an erection. Raina, et al evaluated the daily use of a VCD beginning within two months after radical prostatectomy, and reported that after 9 months of treatment, 17% of patients using the device had return of natural erections sufficient for intercourse, compared with 11% of patients in the nontreatment group 4.

PDE-5 Inhibitors

PDE-5 inhibitors (such as Sildenafil) are the first-line treatment for ED of many etiologies. Several studies have shown that the use of PDE-5 inhibitors might lead to an overall improvement in endothelial cell function in the corpus cavernosum. Chronic use of oral PDE-5 inhibitors suggest a beneficial effect on endothelial cell function. Desouza, et al. concluded that daily sildenafil improves overall vascular endothelial cell function. However, Zagaja, et al. found that men taking oral sildenafil within the first 9 months of a nerve-sparing procedure did not have any erectogenic response 4.

Overall, accumulating scientific literature is suggesting that penile rehabilitation therapies have a positive impact on the sexual function outcome in post-prostatectomy patients. It must be noted that these methods do not cure ED and should be used with caution.

1Penson DF, McLerran D, Feng Z, et al. 5-year urinary and sexual outcomes after radical prostatectomy: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Urol. 2005;173:1701-1705.

2Mulhall J, Land S, Parker M, et al. The use of an erectogenic pharmacotherapy regimen following radical prostatectomy improves recovery of spontaneous erectile function. J Sex Med. 2005; 2:532-540.

3Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Strambi LF, et al. Recovery of spontaneous erectile function after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy with and without early intracavernous injections of alprostadil: results of a prospective, randomised trial. J Urol. 1997;158:1408-1410.

4Gontero P, Fontana F, Bagnasacco A, et al. Is there an optimal time for intracavernous prostaglandin E1 rehabilitation following non- nerve sparing radical prostatectomy? Results from a hemodynamic prospective study. J Urol. 2003;169:2166-2169.

Managing a medical crisis such as a cancer diagnosis can be overwhelming for an individual. Faced with choices about medical options, dealing with disruptions in work, home and family life often leaves little energy left to consider sexual health and intimacy. Maintaining closeness, however, is often a goal within a partnership and can aid in sustaining a relationship through such a crisis. The research is clear about cancer treatment being disruptive to sexual health, yet intimacy is a larger concept that may be fostered even when sexual activity is impaired or interrupted. Last year, when I was asked to speak to the Pacific NW Prostate Cancer Conference about intimacy, I was pleasantly surprised to find a rich body of literature about maintaining intimacy despite a diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

Sexual health and sexuality is a social construct affected by many factors including mood, stress, depression, self-image, physiology, psychology, culture, relational and spiritual factors (Beck et al., 2009; Weiner & Avery-Clark, 2017) Prostate cancer treatment can change relational roles, finances, work life, independence, and other factors including hormone levels.(Beck et al., 2009) Exhaustion (on the part of the patient and the caregiver), role changes, changes in libido and performance anxiety can create further challenges. (Beck et al., 2009; Hawkins et al., 2009; Higano et al., 2012) Recovery of intimacy is possible, and reframing of sexual health may need to take place. Most importantly, these issues need to be talked about, as renegotiation of intimacy may need to take place after a diagnosis or treatment of prostate cancer. (Gilbert et al., 2010)

If the patient brings up sexual health, or we encourage the conversation, there are many research-based suggestions we can provide to encourage recovery of intimacy, several are listed below.

- Manage general health, fitness, nutrition, sleep, anxiety and stress

- Redefine sex as being beyond penetration, consider other sexual practices such as massage/touch, cuddling, talking, use of vibrators, medication, aids such as pumps (Usher et al., 2013)

- Participate in couples therapy to understand partners’ needs, address loss, be educated about sexual function (Wittman et al., 2014; Wittman et al., 2015)

- Participate in “sensate focus” activities (developed by Masters & Johnson in 1970’s as “touch opportunities”) with appropriate guidance (Weiner & Avery-Clark 2017)

Within the context of this information, there is opportunity to refer the patient to a provider who specializes in sexual health and function. While some rehabilitation professionals are taking additional training to be able to provide a level of sexual health education and counseling, most pelvic health providers do not have the breadth and depth of training required to provide counseling techniques related to sexual health- we can, however, get the conversation started, which in the end may be most important.

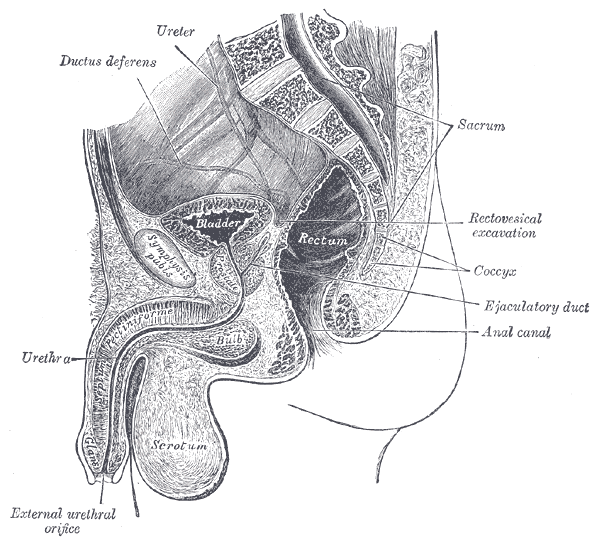

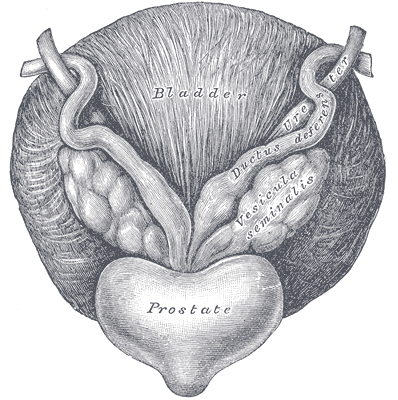

In the men’s health course, we further discuss sexual anatomy and physiology, prostate issues, and look at the research describing models of intimacy and what worked for couples who did learn to renegotiate intimacy after prostate cancer.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2009, April). Sexual intimacy in heterosexual couples after prostate cancer treatment: What we know and what we still need to learn. In Urologic oncology: seminars and original investigations (Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 137-143). Elsevier.

Beck, A. M., Robinson, J. W., & Carlson, L. E. (2013). Sexual Values as the Key to Maintaining Satisfying Sex After Prostate Cancer Treatment : The Physical Pleasure–Relational Intimacy Model of Sexual Motivation. Archives of sexual behavior, 42(8), 1637-1647.

Gilbert, E., Ussher, J. M., & Perz, J. (2010). Renegotiating sexuality and intimacy in the context of cancer: the experiences of carers. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 998-1009.

Hawkins, Y., Ussher, J., Gilbert, E., Perz, J., Sandoval, M., & Sundquist, K. (2009). Changes in sexuality and intimacy after the diagnosis and treatment of cancer: the experience of partners in a sexual relationship with a person with cancer. Cancer nursing, 32(4), 271-280.

Higano, C. S. (2012). Sexuality and intimacy after definitive treatment and subsequent androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(30), 3720-3725.

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., Gilbert, E., Wong, W. T., & Hobbs, K. (2013). Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nursing, 36(6), 454-462.

Weiner, L., Avery-Clark, C. (2017). Sensate Focus in Sex Therapy: The Illustrated Manual. Routledge, New York.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., An, L., Palapattu, G., & Montie, J. E. (2014). Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(9), 2509-2515.

Wittmann, D., Carolan, M., Given, B., Skolarus, T. A., Crossley, H., An, L., ... & Montie, J. E. (2015). What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: toward the development of a conceptual model of couples' sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. The journal of sexual medicine, 12(2), 494-504.

I love adding flax seed to my recipes when I bake. I even hide it in yogurt with crushed graham crackers for my kids. It is a powerful nutrient that can be consumed without knowing it! Although the specific mechanism for its efficacy on prostate health continues to be researched, studies over the last several years applaud flax seed for its benefits and encourage me to keep sneaking it in my family’s diet.

In 2008, Denmark-Wahnefried et al. performed a study to see if flax seed supplementation alone (rather than in combination with restricting dietary fat) could decrease the proliferation rate of prostate cancer prior to surgery. Basically, flax seed is a potent source of lignan, which is a phytoestrogen that acts like an antioxidant and can reduce testosterone and its conversion to dihydrotestosterone. It is also rich in plant-based omega-3 fatty acids. In this study, 161 prostate cancer patients, at least 3 weeks prior to prostatectomy, were divided into 4 groups: 1) normal diet (control); 2) 30g/day of flax seed supplementation; 3) low-fat diet; and 4) flax seed supplementation combined with low-fat diet. Results showed the rate of tumor proliferation was significantly lower in the flax seed supplemented group. The low-fat diet was proven to reduce serum lipids, consistent with previous research for cardiovascular health. The authors concluded, considering limitations in their study, flax seed is at least safe and cost-effective and warrants further research on its protective role in prostate cancer.

In 2008, Denmark-Wahnefried et al. performed a study to see if flax seed supplementation alone (rather than in combination with restricting dietary fat) could decrease the proliferation rate of prostate cancer prior to surgery. Basically, flax seed is a potent source of lignan, which is a phytoestrogen that acts like an antioxidant and can reduce testosterone and its conversion to dihydrotestosterone. It is also rich in plant-based omega-3 fatty acids. In this study, 161 prostate cancer patients, at least 3 weeks prior to prostatectomy, were divided into 4 groups: 1) normal diet (control); 2) 30g/day of flax seed supplementation; 3) low-fat diet; and 4) flax seed supplementation combined with low-fat diet. Results showed the rate of tumor proliferation was significantly lower in the flax seed supplemented group. The low-fat diet was proven to reduce serum lipids, consistent with previous research for cardiovascular health. The authors concluded, considering limitations in their study, flax seed is at least safe and cost-effective and warrants further research on its protective role in prostate cancer.

In 2017, de Amorim et al. investigated the effect of flax seed on epithelial proliferation in rats with induced benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). The 4 experimental groups consisting of 10 Wistar (outbred albino rats) rats each were as follows: 1) control group of healthy rats fed a casein-based diet (protein in milk); 2) healthy rats fed a flax seed-based diet; 3) hyperplasia-induced rats fed a casein diet; and 4) hyperplasia-induced rats fed a flax seed diet. Silicone pellets full of testosterone propionate were implanted subcutaneously in the rats to induce hyperplasia. Once euthanized at 20 weeks, the prostate tissue was examined for thickness and area of epithelium, individual luminal area, and total prostatic alveoli area. Results showed the hyperplasia induced rats fed a flax seed-based diet had smaller epithelial thickness as well as a reduced proportion of papillary projections found in the prostatic alveoli. These authors determined flax seed exhibits a protective role for the epithelium of the prostate in animals induced with BPH.

Bisson, Hidalgo, Simons, and Verbruggen2014 hypothesized a lignan-fortified diet could decrease the risk of BPH. The authors used an extract rich in lignan obtained from flax seed hulls. Four groups of 12 Wistar rats were used, with 1 negative control group and 3 groups with testosterone propionate (TP)-induced BPH (1 positive control, and 2 with diets containing 0.5% or 1.0% of the extract). Over a 5 week period, the 2 BPH-induced groups consuming the lignan extract starting 2 weeks prior to the BPH induction demonstrated a significant inhibition of prostate growth from the TP compared to the positive control group. These authors concluded the lignan-rich flax seed hull extract prevented BPH induction.

From BPH to prostate cancer, flax seed has proven a noteworthy supplement for preventative health. A tablespoon of flax seed in a muffin recipe is likely not a life-changing dose, but it’s a start. Nutrition Perspectives for the Pelvic Rehab Therapist enlightens practitioners with even more healthy choices, and Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation gives you the necessary tools to help patients recover from prostate cancer.

Demark-Wahnefried, W., Polascik, T. J., George, S. L., Switzer, B. R., Madden, J. F., Ruffin, M. T., … Vollmer, R. T. (2008). Flax seed Supplementation (not Dietary Fat Restriction) Reduces Prostate Cancer Proliferation Rates in Men Presurgery. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention : A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 17(12), 3577–3587. http://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0008

de Amorim Ribeiro, I.C., da Costa, C.A.S., da Silva, V.A.P. et al. (2017). Flax seed reduces epithelial proliferation but does not affect basal cells in induced benign prostatic hyperplasia in rats. European Journal of Nutrition. 56: 1201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-016-1169-1

Bisson JF, Hidalgo S, Simons R, Verbruggen M. 2014. Preventive effects of lignan extract from flax hulls on experimentally induced benign prostate hyperplasia. Journal of Medicinal Food. 17(6): 650-656. http://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2013.0046

In 2007, after only speaking on the phone and never meeting in person, my new friend and colleague Stacey Futterman and I presented at the APTA National Conference on the topic of male pelvic pain. It was a 3 hour lecture that Stacey had been asked to give, and she invited me to assist her upon recommendation of one of her dear friends who had heard me lecture. I still recall the frequent glances I made to match the person behind the voice I had heard for so many long phone calls.

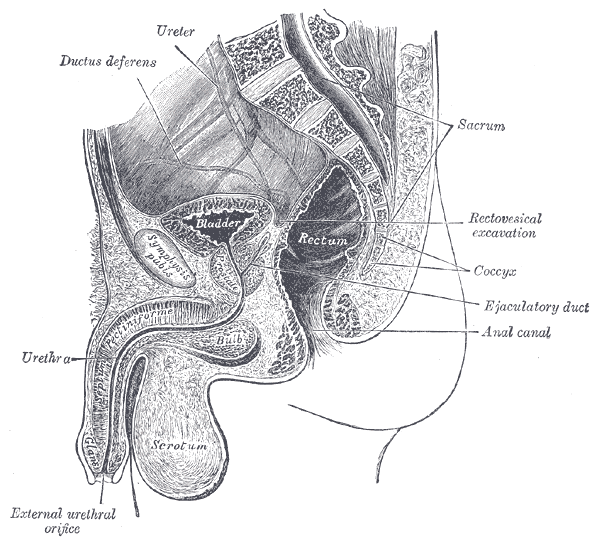

Upon recommendation of Holly Herman, we took this presentation and developed it into a 2 day continuing education course, creating lectures in male anatomy (we definitely did not learn about the epididymis in my graduate training), post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, and a bit about sexual health and dysfunction. Although it truly seems like the worst imaginable question, we asked each other “should we allow men to attend?” As strange as this question now seems, it speaks volumes about the world of pelvic health at that time; mostly female instructors taught mostly female participants about mostly female conditions.

Upon recommendation of Holly Herman, we took this presentation and developed it into a 2 day continuing education course, creating lectures in male anatomy (we definitely did not learn about the epididymis in my graduate training), post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, and a bit about sexual health and dysfunction. Although it truly seems like the worst imaginable question, we asked each other “should we allow men to attend?” As strange as this question now seems, it speaks volumes about the world of pelvic health at that time; mostly female instructors taught mostly female participants about mostly female conditions.

Make no mistake- women’s health topics were and are deserving of much attention in our typically male-centered world of medicine and research. Maternal health in the US is dreadful, and gone are the days when providers should allow urinary incontinence or painful sexual health to be “normal”, yet it is often described as such to women who are brave enough to ask for help. Times have changed for the better for us all.

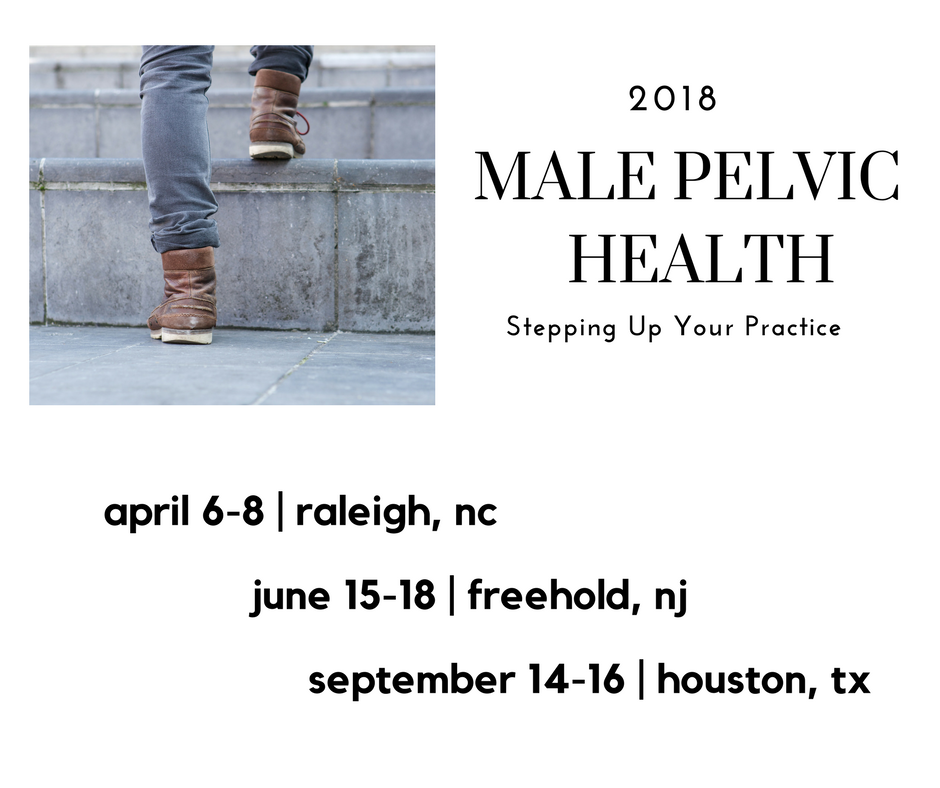

The Male Pelvic Floor Course was first taught in 2008, and so far, 22 events have taken place in 18 different cities. 73 men have attended the course to date, with increasing numbers represented at each course. Rather than 20-25 attendees, the Institute is seeing more of the men’s health course filling up with 35-40 participants. In my observations, the men who attend the course are often very experienced, have excellent orthopedic and manual therapy skills, and have personalities that fit very well into the sensitive work that is pelvic rehabilitation.

The course was expanded to include 3 days of lectures and labs, and this expansion allowed more time for hands-on skills in examination and treatment. The schedule still covers bladder, prostate, sexual health and pelvic pain, and further discusses special topics like post-vasectomy syndrome, circumcision, and Peyronie’s disease. In my own clinical practice, learning to address penile injuries has allowed me to provide healing for conditions that are yet to appear in our journals and textbooks. As I often say in the course, we are creating male pelvic rehabilitation in real time.

Because the course often has providers in attendance who have not completed prior pelvic health training, instruction in basic techniques are included. For the experienced therapists, there are multiple lab “tracks” that offer intermediate to advanced skills that can be practiced in addition to the basic skills. Adaptations and models are used when needed to allow for draping, palpation, and education when working with partners in lab, and space is created for those therapists who want to learn genital palpation more thoroughly versus those who are deciding where their comfort zone is at the time. One of the more valuable conversations that we have in the course is how to create comfort and ease in when for most us, we were raised in a culture (and medical training) where palpation of the pelvis was not made comfortable. Hearing from the male participants about their bodies, how they are affected by cultural expectations, adds significant value as well.

We need to continue to create more coursework, more clinical training opportunities so that the representation of those treating male patients improves. If you feel ready to take your training to the next level in caring for male pelvic dysfunction, this year there are three opportunities to study. I hope you will join me in Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction and Treatment.

At a hair salon, I once saw a plaque that declared, “I’m a beautician, not a magician.” This crossed my mind while reading research on radical prostatectomy, as knowing the baseline penile function of men before surgery seemed challenging. Restoring something that may have been subpar prior to surgery can be a daunting task, and it can cause discrepancies in results of clinical trials. Despite this, two recent studies reviewed the current and future penile rehabilitation approaches post-radical prostatectomy.

Bratu et al.2017 published a review referring to post-radical prostatectomy (RP) erectile dysfunction (ED) as a challenge for patients as well as physicians. They emphasized the use of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) Questionnaire to establish a man’s baseline erectile function, which can be affected by factors such as age, diabetes, alcohol use, smoking habits, heart and kidney diseases, and neurological disorders. The higher the IIEF score preoperatively, the higher the probability of recovering erectile function post-surgery. The experience of the surgeon and the technique used were also factors involved in ED. Radical prostatectomy is a trauma to the pelvis that negatively affects oxygenation of the corpora cavernosum, resulting in apoptosis and fibrotic changes in the tissue, leading to ED. Minimally invasive surgery allows a significantly lower rate of post-RP ED with robot assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) versus open surgery. The cavernous neurovascular bundles get hypoxic and ischemic regardless of the technique used; therefore, the authors emphasized early post-op penile rehabilitation to prevent fibrosis of smooth muscle and to improve cavernous oxygenation for the potential return of satisfactory sexual function within 12-24 months.

Clavell-Hernandez and Wang2017 [and Bratu et al., (2017)] reported on various aspects of penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy. The treatment with the most research to support its efficacy and safety was oral phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors (PDE5Is), which help relax smooth muscle and promote erection on a cellular level. Sildenafil, vardenafil, avanafil, and tadalafil have been studied, either used on demand or nightly. Tadalafil had the longer half-life and was considered to have the greatest efficacy. Nightly versus on-demand for any PDE5I was variable in its results. Intracavernosal injection (ICI) and intraurethral therapy using alprostadil for vasodilation improved erectile function, but it caused urethral burning and penile pain. Vacuum erection devices (VED) promoted penile erection via negative pressure around the penis, bringing blood into the corpus cavernosum. There was no need for intact corporal nerve or nitric oxide pathways for proper function, and it allowed for multiple erections in a day. Intracavernous stem cell injections provided a promising approach for ED, and they may be combined with PDE5Is or low-energy shockwave therapy. Ultimately, the authors concluded early penile rehabilitation should involve a combination of available therapies.

Restoring vascularity to healing tissue is a primary goal in rehabilitation, and the sooner the better. Disruption of cavernous nerves and penile tissue post-RP demands rehabilitation, and some methods have more supporting clinical evidence than others. Newer approaches require more exposure and clinical trials for efficacy and long term outcomes. Clinicians should pay attention to updated research and consider taking continuing education courses such as Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation or Oncology and the Male Pelvic Floor.

Bratu, O., Oprea, I., Marcu, D., Spinu, D., Niculae, A., Geavlete, B., & Mischianu, D. (2017). Erectile dysfunction post-radical prostatectomy – a challenge for both patient and physician. Journal of Medicine and Life, 10(1), 13–18.

Clavell-Hernández, J., & Wang, R. (2017). The controversy surrounding penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy. Translational Andrology and Urology, 6(1), 2–11. http://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2016.08.14

The Center for Disease Control reports that prostate cancer is the most common form of male cancer in the United States (just ahead of lung cancer and colorectal cancer), and the American Cancer Society estimates that 1 in 7 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer at some point in their lifetime. With prostate cancer being so common, it is likely that a male with symptoms of urinary incontinence following a prostatectomy may show up at your clinic’s door for treatment. What do you do? Whether you have extensive training for male pelvic floor disorders or are just starting your initial training for pelvic floor dysfunctions, you likely have some intervention skills to help this population.

A recent case report in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, outlines management of a 76-year-old male patient with mixed urinary incontinence postprostatectomy 10 years. This case report does a nice job describing not just physical therapy (PT) interventions, but also multifaceted management of a typical patient post radical prostatectomy. The case report describes a thorough history, systems review, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) examination, tests &measures, and outcome assessment. Our discussion will focus on interventions as you may already possess the skills for several of the treatments included in this patient’s plan of care.

A recent case report in the Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, outlines management of a 76-year-old male patient with mixed urinary incontinence postprostatectomy 10 years. This case report does a nice job describing not just physical therapy (PT) interventions, but also multifaceted management of a typical patient post radical prostatectomy. The case report describes a thorough history, systems review, pelvic floor muscle (PFM) examination, tests &measures, and outcome assessment. Our discussion will focus on interventions as you may already possess the skills for several of the treatments included in this patient’s plan of care.

The patient’s complaints were mixed urinary incontinence (UI) symptoms including 3-4 pads per day and 1 pad at night. He reported nocturia 3-4 times per night. 2-3 times per week he had large UI episodes that soaked his outwear. Also, he complained of inability to delay voiding, and UI with walking to the bathroom, sit to stand, lifting, coughing, and sneezing.

For the patients’ urge UI symptoms, behavioral interventions were utilized. The patient completed PFM contractions to inhibit detrusor contractions and suppress urgency (urge control technique). Educating the patient on correct PFM contraction isolation was a very important component of this patients’ treatment. Verbal, digital, and surface electromyography (sEMG) techniques were used to ensure correct PFM contraction and to reduce Valsalva. Clinical decision making for home exercise program utilized dominant PFM fiber types and the patients’ performance on the PERFECT PFM strength testing system described by Laycock. (External Urethral Sphincter is predominantly Type II fast twitch muscle fiber in males and Levator Ani is predominantly Type I slow twitch.) For the home program, the patient completed progressive reps and sets of 10” (targets slow twitch) and 2” (targets fast twitch) PFM isometrics in supine progressing to standing. (There is a chart with additional details on PFM home program for each visit in the case report.) Additionally, instruct and use of “the knack” (volitional PFM contraction before and during cough or other physical exertions to prevent UI) for activities that the patient usually had UI with including sit to stand transfer, lifting, coughing, and sneezing was essential for the patients’ symptoms. PFM coordination training with sEMG helped reduce his accessory muscle recruitment patterns and Valsalva. Bladder retraining and lifestyle recommendation were important (per his 3-day bladder diary) as he was consuming 3 cups of coffee and 4 cups or more of tea a day, likely contributing to urgency and urge UI symptoms. Also, he was informed regarding the effect of obesity on UI (as his BMI was 35.9 placing him in the obese range) and that modest amounts of weight loss maybe sufficient for UI reduction. Abdominal exercises targeting Transversus Abdominus were also prescribed for their role in core support with PFM’s. Lastly, electrical stimulation was not included in this patients’ plan of care due to the patients’ cardiac history and pacemaker, as well as, he could initiate PFM contraction and utilize urge control techniques appropriately.

The outcome for this patient was positive. He attended 5 PT sessions over a 3-month period. He did have to cancel two appointments between the 4th and 5th visits due to an emergency surgery to place two cardiac stents. He had reduced urinary leakage indicated by reduced undergarment changes and reduced pad usage per day. His pads were less saturated and he no longer had leakage that spread to his outwear. He had a 50% reduction in UI episodes reported on his bladder diary and a 50% reduction in nocturia from 4 times to 2 times per night. He reported reduced daily urinary frequency from 7 to 5 times per day with no instances of severe urgency. He demonstrated improved PERFECT score of 4, 10, 8, 10 (initially his score was 2, 5, 3, 5) indicating improved PFM strength and endurance. Also, he had improved PFM coordination as he could isolate PFM contraction without Valsalva or accessory muscle activation. He also had one strength grade improvement with abdominal strength. All that being said, most importantly, this patient had improved rating on the outcome questionnaire (International Continence Society male Short Form (ICSmaleSF)) at discharge indicating improved quality of life. At initial evaluation, this patient rated “a lot” (3 on ICSmaleSF) when asked how much the urinary symptoms interfered with his life, at discharge he reported “not at all” (0 on ICSmaleSF).

One component to this case that I found fascinating was the duration of time that had passed since this patients’ prostatectomy. It had been 10 years since this patient had his surgical procedures. He had never been offered physical therapy or knew about it as a possible treatment for his symptoms. Additionally, that he could have such success with improvements in voiding and incontinence function, as well as improved quality of life as long as 10 years’ post-prostatectomy.

This case report is a comprehensive glimpse of what physical therapy assessment and treatment may look like for a patient with urinary dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. This patient had great improvements with positive changes enhancing his quality of life. So, if you are considering adding treatment of this population to your practice consider attending Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation, available this July in Annapolis, MD or September in Seattle, WA.

"Cancer Among Men", Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Roscow, A. S., & Borello-France, D. (2016). Treatment of Male Urinary Incontinence Post–Radical Prostatectomy Using Physical Therapy Interventions. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy, 40(3), 129-138.

Spending the past 5 years watching a lot of Disney Junior and reading Dr. Seuss, professional journal reading is generally reserved for the sanctuary of the bathroom. When patients ask if I’ve heard of certain new procedures or therapies, I try to sound intelligent and make a mental note to run a PubMed search on the topic when I get home. Making the effort to stay on top of research, however, makes you a more confident and competent clinician for the information-hungry patient and encourages physicians to respect you when it comes to discussing their patients.

A 2016 article in Translational Andrology and Urology, Lin et al., explored rehabilitation of men post radical prostatectomy on a deeper level, trying to prove that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) promotes nerve regeneration. In many radical prostatectomies, even when the nerve-sparing approach is used, there is injury to the cavernous nerves, which course along the posterolateral portion of the prostate. Cavernous nerve injury can cause erectile dysfunction in 60.8-93% of males postoperatively. The authors discussed Schwann cells as being vital for maintaining integrity and function of peripheral nerves like the cavernous nerve. They hypothesized that BDNF, a member of the neurotrophin family that supports neuron survival and prevents neuronal death, activates the JAK/STAT (Janus kinase /signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway in Schwann cells, thus facilitating axonal regeneration via secretion of cytokines (IL-6 and OSM-M). Through scientific experiment on a cellular level (please refer to the article for the specific details), the authors were able to confirm their hypothesis. Schwann cells do, in fact, produce cytokines that contribute to the regeneration of cavernous nerves.

From a different cellular perspective, Haahr et al., (2016) performed an open-label clinical trial involving intracavernous injection of “autologous adipose-derived regenerative cells” (ADRCs) in males experiencing erectile dysfunction (ED) after radical prostatectomy. Current treatments with PDE-5 inhibitors do not give satisfactory results, so the authors performed a human phase 1, single-arm trial to further the research behind the use of adipose-derived stem cells for ED. Some limitations included the study was un-blinded and had no control group. Seventeen males who had ED after radical prostatectomy 5-18 months prior to the study were followed for 6 months post intracavernosal transplantation. The primary outcome was safety/tolerance of stem cell treatment, and the secondary was improvement of ED. The single intracavernosal injection of freshly isolated autologous adipose-derived cells resulted in 8 of 17 men regaining erectile function for intercourse; however, the men who were not continent did not regain erectile function. The end results showed the procedure was safe and well-tolerated. There was a significant improvement in scores for the International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5), suggesting this therapy may be a promising one for ED after radical prostatectomy.

In the clinic, we need to treat our patients to the best of our ability. Taking the Post-Prostatectomy Patient Rehabilitation course is vital if even just one patient enters your office seeking treatment. Keeping up on research (even that which seems too full of forgotten science) and learning new manual techniques and exercises can help us rise as clinicians prepared to optimize patients’ function.

Lin, G., Zhang, H., Sun, F., Lu, Z., Reed-Maldonado, A., Lee, Y.-C., … Lue, T. F. (2016). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes nerve regeneration by activating the JAK/STAT pathway in Schwann cells. Translational Andrology and Urology, 5(2), 167–175. http://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2016.02.03

Haahr, M. K., Jensen, C. H., Toyserkani, N. M., Andersen, D. C., Damkier, P., Sørensen, J. A., … Sheikh, S. P. (2016). Safety and Potential Effect of a Single Intracavernous Injection of Autologous Adipose-Derived Regenerative Cells in Patients with Erectile Dysfunction Following Radical Prostatectomy: An Open-Label Phase I Clinical Trial. EBioMedicine, 5, 204–210. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.01.024

A recent article titled "Pain, Catastrophizing, and Depression in Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome" describes the variations in patient symptom report and perception of the condition. The article describes the evidence-based links between chronic pelvic pain and anxiety, depression, and stress, and highlights the important role that coping mechanisms have in reported pain and quality of life levels. One of the ways in which a provider can assist in patient perception of health or lack thereof is to provide current information about the condition, instruct the patient in pathways for healing, and provide specific care that aims to alleviate concurrent neuromusculoskeletal dysfunction.

Most pelvic rehabilitation providers will have graduated from training without being informed about chronic pelvic pain syndromes. And as most pelvic rehabilitation providers receive their pelvic health knowledge from continuing education courses, unless a therapist has attended coursework specifically about male patients, the awareness of male pelvic dysfunctions remains low. If you are interested in learning about male pelvic health issues, the Institute introduces participants to male pelvic health in the Level 2A series course. The practitioner who would like more information about male patients can attend the Male Pelvic Floor Function, Dysfunction, and Treatment course that is offered in Torrance, CA at the end of this month.

The authors in this study point out that chronic pelvic pain is not a disease, but rather is a symptom complex. Despite the persistent attempts to identify a specific pathogen as the cause of prostatitis-like pain, this article states that "…no postulated molecular mechanism explains the symptoms…" As with any other chronic pain condition, research in pain sciences tells us that behavioral tendencies such as catastrophizing is not associated with improved health. The authors utilized a psychotherapy model in developing a cognitive-behavioral symptom management approach and found significant reductions in CPP symptoms. The relevance of this information for our patient population includes having the ability to screen our patients for depression, to recognize tendencies to catastrophize, and to implement useful strategies for our patient.

What does your facility currently use as a depression screening tool? Having this information at hand when communicating with a referring provider is very helpful. Explaining the biology of the vicious cycle of emotional stress and pain responses can help a patient understand why following up on a referral to a psychologist or counselor may be helpful towards his health. Identifying catastrophizing as the patient who is hypervigilent about symptoms, ruminates about his condition, expresses an attitude of helplessness, or magnifies the threat of the perceived pain can aid in identification of the patient who needs more than a few stretches, a TENS unit, or manual therapy.

A new course offered this year by the Institute will provide excellent foundational background information as well as practical patient care techniques about emotional and psychological principles that influence chronic pain. This course, Integrating Meditation and Neuropsych Principles to Maximize Physical Therapy Interventions, is instructed by Nari Clemons, a physical therapist who excels in pelvic rehabilitation, and Shawn Sidhu, a psychiatrist with a special interest in mind body medicine. The course is offered only one time this year, in September in Illinois, so sign up early!