This post was written by Jennafer Vande Vegte, MSPT, BCB-PMD, PRPC. You can catch Jennafer teaching the Pelvic Floor Level 2B course this weekend in Columbus.

"I hate my vagina and my vagina hates me. We have a hate- hate relationship'" said my patient Sandy (name has been changed) to me after treatment. Sandy's harsh words settled between us. I understood perfectly why she might feel this way. I have been treating Sandy on and off for four years. She has had over fifteen pelvic surgeries. Her journey started with a hysterectomy and mesh implantation to treat her prolapsed bladder. She did well for several months and then her pain began. Her physician refused to believe that her pain was coming from the mesh. This pattern was repeated for several years as Sandy tried in vain to explain her pain to her medical providers. She was told her pain was all in her head and put on psych meds. Finally, five years later, Sandy found her way to an experienced urogynecologist who recognized that Sandy was having a reaction to the mesh from her prolapse surgery. It turns out that Sandy's body rejected the mesh like an allergen. Her tissues had built up fibrotic nodules to protect itself from exposure to the mesh. It has taken years and multiple operations to remove all the mesh and all the nodules. Of course then Sandy's prolapse recurred as well as her stress incontinence and she recently had surgery to try to give her some support. In PT we attempted to manage her pain, normalize her pelvic floor function, strengthen her supportive muscles and fascia. Due to years of chronic pain, her pelvic floor would spasm so completely internal work was not possible. Sandy began to also get Botox injections to her pelvic floor and pudendal nerve blocks. She uses Flexeril, Lidocaine and Valium vaginally three times a day to manage her chronic pelvic pain. She is on disability because she cannot work. Later this month Sandy will have her 16th surgery to remove a hematoma caused by her previous surgery and another nodule that we found in her left vulva. Sandy is the most complicated case of mesh complication that I have seen in my practice, however I regularly see women who have had problems with mesh that we manage through PT and also women that have had mesh removal. No one expects to have complications with their surgery and when they do it can be life altering.

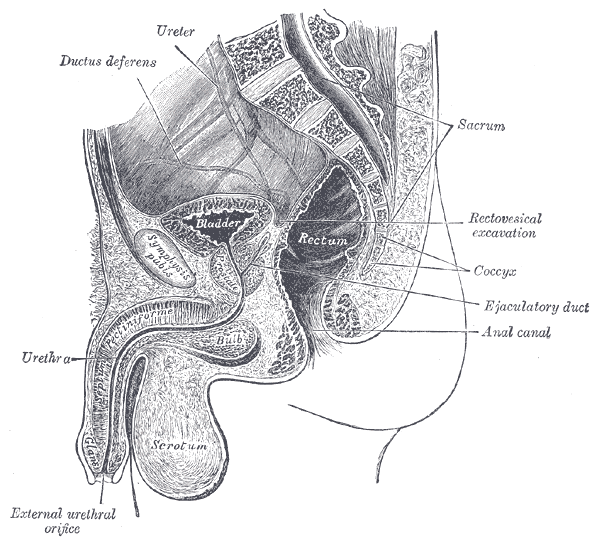

In a recent review of the literature surrounding mesh complications Barski and Deng cite that over 300,000 women in the US will undergo surgical correction for stress incontinence (SUI) or pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Mesh related complications have been reported at rates of 15-25%. Mesh removal occurs at a rate of 1-2%. Mesh erosion will occur in 10% of women. There are over 30,000 cases in US courts today related to pain and disability due to mesh complications. The authors looked at mesh complication statistics from studies concerning three surgical procedures: mid urethral slings, transvaginal mesh and abdominal colposacropexy .

The authors note there are sometimes reasons why mesh goes wrong: it is used for the wrong indication, there could be faulty surgical technique, and the material properties of mesh are inherently problematic for some women. Risk factors in patient selection are previous pelvic surgery, obesity and estrogen status. There are several types of complications described: trauma of insertion, inflammation from a foreign body reaction, infection, rejection, and compromised stability of the prosthesis over time. With mid urethral slings there were also several other complications listed such as over active bladder (52%), urinary obstruction (45%), SUI (26%) mesh exposure (18%) chronic pelvic pain (18%). For transvaginal mesh, reported rate of erosion was 21%, dysparunia 11%, mesh shrinkage, abscess and fistula totaled less than 10%. Transvaginal obturator tape was noted to be traumatic for the pelvic floor. Infections that might occur in the obturator fossa require careful and through treatment. Of women who have complications 60% will end up requiring surgical removal. It is imperative to find a surgeon who is experienced and skilled with this procedure as complete excision can be difficult and there are risks of bleeding, fistula, neuropathy and recurrence of prolapse and SUI. After recovery, 10-50% of women who have had excision will have another surgery to correct POP or SUI.

As pelvic health physical therapists we are strategically poised to both help women manage SUI and POP conservatively. We also have the skills needed to help rehabilitate women dealing with complications from mesh, either to avoid removal or after removal. Our job goes beyond the physical too, often helping women cope with the emotional toll that can parallel her medical journey. At PF2B we will discuss conservative prolape management and give you tools to help patients cope with chronic pain. Would love to see you there.

In our weekly feature section, Pelvic Rehab Report is proud to present this interview with Herman & Wallace instructor Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, PRPC, BCB-PMD

How did you get started in pelvic rehab?

I got started in pelvic rehab by treating and specializing in SIJ and low back dysfunction. I used ultrasound imaging to retrain the local core muscles including the transverse abdominis, lumbar multifidus, and the pelvic floor muscles. In treating these patients, not only did they improve with respects to their back pain, but their incontinence improved as well! I then started getting referrals from doctors for incontinence patients. So I took PF1 and as they say, the rest is history! I know that pelvic rehab is my calling. I am impassioned about this subject and love treating these patients. I also thoroughly enjoy teaching about the pelvic floor and the pelvic ring. I truly feel I am one of the lucky ones to actually love what I do!

What do you find most rewarding about treating this patient population?

I am passionate about treating this patient population because it makes such a difference in their lives! I have had more patients than I like to admit say that if they did not find me and get on my schedule, they would have killed themselves due to their pain. This is so sad and alarming to me that individuals have gotten to the point of considering those thoughts. I feel blessed that I am in a position to not only improve their lives in the physical sense but also in the emotional one by lessoning their pain and improving their outlook on life! To me there is nothing more rewarding than seeing this dramatic of a change in a patient.

What do you find most rewarding about teaching?

One reason I love teaching is because it is a way to help improve the lives of more people suffering with pelvic disorders! There are not enough therapists that specialize in the pelvic floor and by teaching other therapists how to appropriately treat pelvic floor dysfunction, it positively impacts more people’s lives! I always find it magical when a course participant is hesitant and nervous to take the course. Then after the course they are excited and enthusiastic to treat this patient population and to learn more about this field. This is very rewarding to me and a reason I look forward to teaching each and every course.

If you could get a message to all therapists about pelvic rehab, what would it be?

One message I would try to get out to therapists about pelvic rehab is to get out and talk about it! Discuss what you do with physicians, the community, as well as people you meet in every day life. Often, when someone finds out what you do, you will get questions asked of you. However, don’t wait for this! There are so many women and men suffering in silence thinking that there is nothing they can do. So get out there and tell them what you do and how you can help can improve lives! Don’t be hesitant or shy, be energetic and excited to share your knowledge and educate the public about what we do as pelvic therapists!

This post features an interview with Eric Dinkins, PT, MSPT, OCS, MCTA, CMP, Cert. MT, who will be instructing the brand new course, Manual Therapy for the Lumbo-Pelvic-Hip Complex: Mobilization with Movement including Laser-Guided Feedback for Core Stabilization. Pelvic Rehab Report sat down with Eric to learn a little bit more about his course and his clinical approach

Can you describe the clinical/treatment approach/techniques covered in this continuing education course?

During this two day lab based course, clinicians will learn anatomy, assessment techniques, and manual therapy techniques that are designed to minimize pain and restore function immediately. As a bonus, clinicians will be introduced to stabilization exercises utilizing the Motion Guidance visual feedback system for these areas. This system allows for immediate feedback for both the clinician and the patient on determining preferred or substituted movement patterns, and enhancing motor learning to quickly address these patterns if desired.

What inspired you to create this course?

Women's and Men's health patients often have concurrent orthopedic problems that contribute to the pain or dysfunction that they are experiencing in the lumbar spine, pelvis, hips and sexual organs. There are few manual therapy courses offered that are able to bridge a gap between these two topics. This makes for a unique opportunity to offer manual therapy techniques that can address these problems and help improve clinic outcomes.

What resources and research were used when writing this course?

The books and resources I pulled from include:

Mulligan Concept of Manual Therapy 2015

Travell and Simmons Volume 2. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual. The Lower Extremities

Principles of Manual Medicine 4th Edition

www.motionguidance.com

Why should a therapist take this course? How can these skill sets benefit his/ her practice?

PT's, PTA, DO's and DC's should take this course to give them knowledge and manual skills of pain free techniques to offer their Women's Health, Men's Health, and pregnancy patients with orthopedic conditions.

Among the challenges in research for chronic pelvic pain is the lack of consensus about diagnosis and intervention. Prominent researchers and physicians J. Curtis Nickel and Daniel Shoskes describe a methodology for classification of male chronic pelvic pain using phenotyping, which can be simply described as “a set of observable characteristics.” The authors point out in this article that men with complaints of pelvic pain have historically been treated with antibiotics, even though now it is known that most cases of “prostatitis” are not true infections. With most patients having chronic pelvic pain presenting with varied causes, symptoms, and responses to treatment, Nickel and Shoskes acknowledge that traditional medical approaches have not been successful.

In an attempt to improve classification of patients and subsequent treatment approaches, the UPOINT system was developed. The domains of the system include urinary, psychosocial, organ specific, infection, neurological/systemic conditions, and tenderness of skeletal muscles, and are listed below. Within each domain, the clinical description has been adapted from the original study (which can be accessed full text at the link above.)

UPOINT Domains

-Urinary: CPSI urinary score > 4, complaints of urinary urgency, frequency, or nocturia, flow rate , 15mL/s and/or obstructed pattern

-Psychosocial: Clinical depression, poor coping or maladaptive behavior such as catastrophizing, poor social interaction

-Organ specific: specific prostate tenderness, leukocytosis in prostatic fluid, haematospermia, extensive prostate calcification

-Infection: exclude patients with evidence of infection

-Neurological/systemic conditions: pain beyond abdomen and pelvis, IBS, fibromyalgia, CFS

-Tenderness of skeletal muscles: palpable tenderness and/or painful muscle spasm or trigger points in perineum or pelvic muscles

Within the initial research utilizing the UPOINT classification system, the authors report that most patients fall into more than one domain, and that the more domains a person is identified with, the more severe the symptoms. The domains leading to the highest impact are the psychosocial, neurological/systemic, and then the tenderness domain. The referenced article points out that the most impactful domains are the ones that are non-prostatocentric, or focused on dysfunction within the prostate itself. Phenotyping may indeed lead to improved classification of and treatment of male chronic pelvic pain. If you are interested in learning more about male chronic pelvic pain, there are still two opportunities to take the Male Pelvic Floor continuing education course this year. In August of this year, the course will take place in Denver, and in November, the male course will return to Seattle.

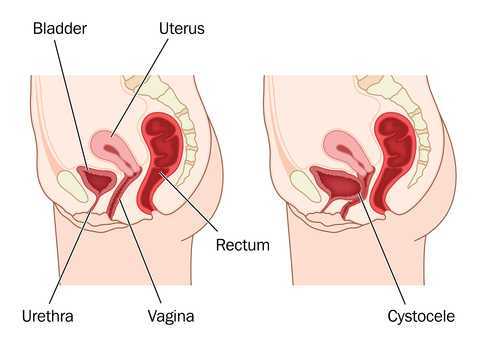

You know how some women report that they have a mild prolapse that feels better if they wear a tampon during strenuous activity, or that a tampon worn (temporarily) helps avoid urinary leakage? Using a tampon instead of a pessary seems like a great fix, with one problem: tampons are not designed to be used as a pessary. They are designed to be absorptive and to expand to fill the vaginal canal as they expand. Some women can even suffer from toxic shock syndrome - a condition related to bacterial infection and associated with super-absorbent tampon use, contraceptives, and diaphragm use. What if an item could be used that is similar to a tampon, but not absorptive, and that provided more support than a cylindrical-shaped tampon? That must have been what Kimberly Clark, the manufacturer of a new product, created to fit this need.

The Impressa is marketed as a device for urinary incontinence that a patient can buy over-the-counter. The product comes in an applicator and can be inserted similarly to the way a tampon is, but the Impressa is not made to absorb leaks. Once inserted, the product has an interesting shape that is designed to help support the urethra. The device comes in 3 sizes labeled 1, 2, and 3, and the product has a "sizing kit" with 2 of each size in a box that can be trialed for finding the best fit. It will be interesting to see how valuable this product is and we will only know as we begin to hear feedback from their use. Pessary fit is a tough process in that providers and patients often have to go through a period of trial and error for best fit, and also because providers are poorly reimbursed for management of pessary fit and use. (Click here to read more on the blog about prolapse and pessaries.)

It appears that the product is not yet widely available, but it will be interesting to hear women's' experiences about the product. Having an option for an affordable, disposable pessary-like device that is available over-the-counter could be a very helpful option to know about. Health professionals can go to the website impressapro.com to send an email requesting a sample or more information. And thank you to certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Joyce Steele for sharing information about the Impressa as this may be something your patients start asking more about. To learn more about prolapse management and female pelvic floor dysfunction, come to one of our intermediate-level continuing education courses, PF2B. The next opportunities to take this class (that aren't sold out!) are in Connecticut, North Carolina, and Missouri this year.

This post was written by Allison Ariail, PT, DPT, CLT-LANA, PRPC, BCB-PMD. You can catch Allison teaching the Pelvic Floor Level 1 course in May in Los Angeles.

Dysmenorrhea is the medical term used for painful menstruation. Symptoms usually begin 1 or 2 days before or the first day of menstruation and include headache, low back and thigh pain, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, and excessive fatigue. Sixty percent of women suffer from dysmenorrhea, with many of these women being incapacitated for up to 3 days each month due to symptoms. There are two types of dysmenorrhea. Primary dysmenorrhea is menstrual pain that is not caused from another disorder or disease. Secondary dysmenorrhea is menstrual pain that is due to a disorder in the pelvic organs including endometriosis, fibroids, adenomyosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, cervical stenosis, or infection. In the past, treatment approaches for primary dysmenorrhea have included the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, hormonal contraceptives, vitamins, and acupuncture. There have not been many studies that look at how physical activity influences the degree of pain for women with primary Dysmenorrhea. However, clinical experience has shown me that some women who begin exercising regularly decrease their dysmenorrhea symptoms compared to what they previously experienced. So I have done a search to find some studies that address this matter.

A Cochrane review found only one study that used a control group. In this study, the experimental group participated in a 12-week walking or jogging program at 70-80% of heart rate range, 3 days a week for 30 minutes. Moos’ Menstrual Distress Inventory was used to measure outcomes. This was given pre-training, post-training, and during the premenstrual and inter-menstrual phases for the three hormonal cycles measured. There were significant lower scores on the Moos’ Menstrual Distress Inventory during the menstrual phase in the group that participated in exercise compared to the control group. Additionally, there was a negative linear trend in scores over the three observed cycles for the training group with no linear trend seen in the control group.1 So the exercise group lessoned the degree of their symptoms over the three months by participating in the walking program!

A study by Maceno de Araujo et al. looked at the severity of primary dysmenorrhea symptoms before and after participating in a two month Pilates exercise regimen 2 times per week for 60 minutes. Outcome measures used included visual analog scale and McGill Pain Questionnaire. Although this study did not use a control group and the number of participants was low (n=10), it did show significant changes in pain scores during menstruation when comparing little to no exercise to a regular exercise program of Pilates. Pain scores due to menstruation prior to the study were 7.89 ± 1.96, and dropped to 2.56 ± .56 with the exercise program!

I found these articles interesting and began to wonder how many women we as therapists could help by knowing this information! I do not think that we as pelvic heath therapists are reaching this population of patient diagnoses. Yes, starting an exercise regimen, especially a walking program, sounds easy to us as physical therapists or occupational therapists. However, it can be daunting to a woman who has not previously participated in any type of exercise program. Meeting with some of these women who suffer from primary dysmenorrhea and evaluating any musculoskeletal dysfunctions that are present, then prescribing an appropriate exercise routine that is individualized for that patient can help the patient stay committed to the program. In finding this information, I am excited to pass it along to my patients and future patients in hopes of improving their life and lessening their discomforts! Join me to discuss this topic as well as others related to the pelvic floor in Los Angeles at PF1!

1. Brown J, Brown S. Exercise for dysmenorrhea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD004142. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004142.pub2.

2. Macêdo de Araújo L; Nunes da Silva JM; Tavares Bastos W; Lima Venutra P. Pain improvement in women with primary dysmenorrhea treated with Pilates. Revista Dor. 2012; 13(2).

Patients who suffer severe bladder damage or bladder disease such as invasive cancer may have the entire bladder removed in a cystectomy procedure. Once the bladder is removed, a surgeon can use a portion of the patient's ileum (the final part of the small intestines) or other part of the intestine to create a pouch or reservoir to hold urine. This procedure can be done using an open surgical approach or a laparoscopic approach. Once this new pouch is attached to the ureters and to the urethra, the "new bladder" can fill and stretch to accommodate the urine. As the neobladder cannot contract, a person will use abdominal muscle contractions along with pelvic floor relaxation to empty. If a person cannot empty the bladder adequately, a catheter may need to be utilized. (A prior blog post reported on potential complications of and resources for learning about neobladder surgery.)

During the recovery from surgery, patients will wear a catheter for a few weeks while the tissues heal. Once the catheter has been removed, patients may be instructed to urinate every 2 hours, both during the day and at night. Because patients will not have the same neurological supply to alert them of bladder filling, it will be necessary to void on a timed schedule. The time between voids can be lengthened to every 3-4 hours. Night time emptying may still occur up to two times/evening. Patient recommendations following the procedure may include that patients drink plenty of fluids, eat a healthy diet, and gradually return to normal activities. Adequate fluid is important in helping to flush mucous that is in the urine. This mucous is caused by the bowel tissue used to create the neobladder, and will reduce over time.

Urinary leakage is more common at night in patients who have had the procedure, and this often improves over a period of time, even a year or two after the surgery. As pelvic rehabilitation providers, we may be offering education about healthy diet and fluid intake, pelvic and abdominal muscle health and coordination, function retraining and instruction in return to activities. In addition to having gone through a major surgical procedure, patients may also have experienced a period of radiation, other treatments, or debility that may limit their activity levels. The Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute is pleased to offer courses by faculty member Michelle Lyons in Oncology and the Pelvic Floor, Part A: Female Reproductive and Gynecologic Cancers, and Part B: Male Reproductive, Bladder, and Colorectal Cancers. If you would like to explore pelvic rehabilitation in relation to oncology issues, there is still time to register for the Part A course taking place in Torrance, California in May! If you would like to host either of these courses at your facility, let us know!

In our weekly feature section, Pelvic Rehab Report is proud to present this interview with Herman & Wallace instructor Peter Philip, PT, ScD, COMT, PRPC

How did you get started in pelvic rehab?

While treating an MD, OB-GYN, he asked me a question regarding a patient that he was treating that was suffering from dyspareunia. I’d just completed my Master's in orthopedic physical therapy and realized that there was an entire section of the body that was "full of muscles, ligaments and nerves” of which I had virtually no knowledge. This bothered me, so I began my own independent research, study and application of skills learned through continuing education, and application of what are typically considered to be ‘orthopedic’ techniques to the pelvic pain/dysfunction population. To my (continued) wonderment, the patients responded exceptionally well, and efficiently.

Who or what inspired you?

Dr. Russell Woodman and Dr. Holly Herman have provided me with the foundational skills and motivation to help and heal those patients suffering.

What have you found most rewarding in treating this patient population?

Many patients have suffered for years prior to ‘finding’ me. Many are despondent, and have given up hope for a cure; resigning themselves to a life of pain. Providing the means of restoring comfort and wellness is gratifying, rewarding and quite frankly, humbling. What an honor it is to help those that suffer regain the life that they thought they’ve lost.

What do you find more rewarding about teaching?

Having the opportunity to assist clinicians (MDs, PTs, DCs) more effectively, efficiently evaluate and treat their patients provides me with the same gratification that treating the patients myself. This, in addition to being able to help those that have not been helped attain their wellness and health they’ve been seeking, often for years.

What was it like the first time you taught a course to a group of therapists?

The first course I taught was in NYC. The air conditioning was broken, and the office had a few, small windows. The ambient temperature was upper nineties, and no breeze. Through the tortuous temperatures, and ‘first time jitters’ I persevered, and the staff were incredible hosts and provided me with guidance that I appreciate to this day!

What trends/changes are you finding in the field of pelvic rehab?

Manual medicine and non-surgical interventions are being more recognized as very viable means to address, and eliminate pain while improving biomechanics and function. Medical practitioners from all fields are consulting with specialists in the field of pelvic pain to better address their patients' suffering. We are at the forefront of interventional treatments, and patients are seeking effective means to eradicate their pain and dysfunction.

If you could get a message to all therapists about pelvic rehab, what would it be?

Review, re-read, re-learn all the anatomy, neuroanatomy, kinematics and never forget to think, think, think.

In a case report published within the past year by physical therapist Karen Litos, a detailed and thorough case study describes the therapeutic progression and outcomes for a woman with significant functional limitation due to a separation of her diastasis recti muscles. The patient in the case is described as a 32-year-old G2P2 African-American woman referred to PT at 7 weeks postpartum. Delivery occurred vaginally with epidural, no perineal tearing, and pushing time of less than an hour. Primary concerns of the patient included burning or sharp abdominal pain when lifting, standing, and walking. Uterine contractions that naturally occurred during breastfeeding also worsened the abdominal pain and caused the patient to discontinue breastfeeding. The patient furthermore reported sensations that her insides felt like they would fall out, and abdominal muscle weakness and fatigue with activity.

Although many other significant details related to history, examination and evaluation were included in the case report, I will focus on the signs, interventions, and outcomes recorded in the paper. Diastasis was measured using finger width assessment and a tape measure. (Although ultrasound is more accurate and valid, palpation of diastasis has been demonstrated to have good intra-rater reliability as used in this study. Measures for interrecti distance (IRD) at time of evaluation were 11.5 cm at the umbilicus, 8 cm above the umbilicus, and 5 cm below the umbilicus. The patient also reported pain on the visual analog scale (VAS) of 3-8/10.

Interventions in rehabilitation included, but were not limited to: instruction in wearing an abdominal binder, appropriate abdominal and trunk strengthening (promotion of efficient load transfer and avoidance of exercises that may worsen separation), biomechanics training with functional tasks such as transfers, self-bracing of abdominals, avoiding Valsalva, postural alignment and symmetrical weight-bearing strategies. Plan of care was developed as 2-3x/week for 2-3 weeks, the patient was seen for 18 visits over a four month period. Therapeutic exercise was progressed to include general hip and trunk muscle strengthening towards a goal of stability during movement. Cardiovascular training progressed to light treadmill jogging and use of an elliptical.

After 18 visits, functional goals were all met and included picking up her baby, holding her baby for 30 minutes, standing or walking for at least an hour. VAS pain score progressed to 0 on the 0-10 scale. The diastasis was measured at discharge to be 2 cm at the umbilicus, 1 cm above the umbilicus, and 0 cm below the umbilicus. This case report is first an excellent example of a detailed case example. Second, while the separation dramatically improved, most importantly, the patient’s function improved and her goals were met. This case is a wonderful example of how sharing details of a patient’s rehabilitation efforts can be useful for other rehabilitation therapists to consider when developing a plan of care.

If you are interested in discussing more about postpartum care, check out the first in our peripartum series, “Care of the Pregnant Patient” taking place next in Boston in May with Institute co-founder Holly Herman.

This post was written by Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCIA-PMB, who teaches the course Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain: Musculoskeletal Factors in Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. You can catch Elizabeth teaching this course in April in Milwaukee.

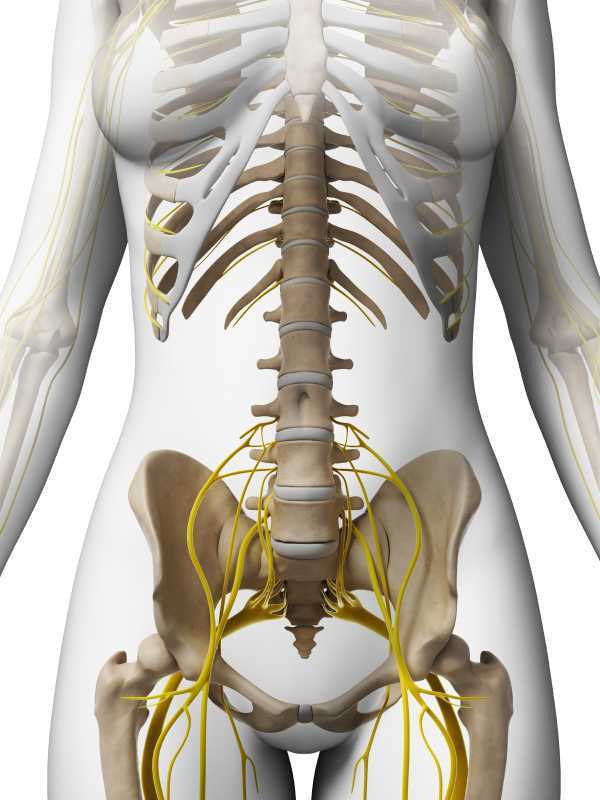

Chronic pelvic pain has multifactorial etiology, which may include urogynecologic, colorectal, gastrointestinal, sexual, neuropsychiatric, neurological and musculoskeletal disorders. (Biasi et al 2014) Herman and Wallace faculty member, Elizabeth Hampton PT, WCS, BCB-PMD has developed an evidence based systematic screen for pelvic pain that she presents in her course “Finding the Driver in Pelvic Pain”. One possible origin of pelvic pain as well as chronic psoas pain and hypertonus may arise from genitofemoral, ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric neuralgia, the screening of which is addressed in the “Finding the Driver” extrapelvic exam.

The iliohypogastric nerve arises from the anterior ramus of the L1 spinal nerve and is contributed to by the subcostal nerve arising from T12. This sensory nerve travels laterally through the psoas major and quadratus lumborum deep to the kidneys, piercing the transverse abdominis and dividing into the lateral and anterior cutaneous branches between the TVA and internal oblique. The anterior cutaneous branch provides suprapubic sensation and the lateral cutaneous branch provides sensation to the superiolateral gluteal area, lateral to the area innervated by the superior cluneal nerve. (10)

The ilioinguinal nerve arises from the L1 spinal levels, passes through the psoas major inferior to the iliohypogastric nerve, across the quadratus lumborum and iliacus and lastly through the transversus abdominis along with the iliohypogastric nerve between the transverse abdominis and the internal oblique muscle. (7) The ilioinguinal nerve supplies the skin of the medial thigh, upper part of the scrotum/labia as well as penile root (5).

The genitofemoral nerve arises from the L1 and L2 spinal levels and splits into the genital and femoral branches after passing through the psoas muscle. (1). The genital branch (motor and sensory) passes through the inguinal canal and innervates the upper area of the scrotum of men. In women it runs alongside the round ligament and innervates the area of the skin of the mons pubis and labia majora. The motor function of the genital branch is associated with the cremasteric reflex. The femoral (sensory) branch runs alongside the external iliac artery, through the inguinal canal and innervates the skin of the upper anterior thigh. (8)

Differential diagnosis of entrapment of one of the three nerves can be challenging due to their overlapping sensory innervations and anatomic variability. Rab et al found up to 4 different patterns of anatomical variability in these nerve pathways. (9)

Transient or lasting genitofemoral, ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric neuralgia results from compression or irritation of these nerves anywhere along their pathway: from their spinal origin to distal pathways. Cesmebasi at al report that “neuropathy can result in paresthesias, burning pain, and hypoalgesia associated with the nerve distributions. “ (11) These entrapments may be associated with surgery, T12-L2 segmental dysfunction or HNP, constipation and is commonly observed clinically alongside psoas overactivity and pain. Lichtenstein found that up groin pain after hernia surgery ranged from 6-29% with Bischoff et al (2012) (6) denoting the post-operative neuralgia ranging from 5-10%.

Differential diagnosis of nerve entrapments are key skills in the screening of musculoskeletal contributing factors to pelvic pain and physical therapists are uniquely skilled to put all of the puzzle pieces together in these complex clients. Finding the Driver is being offered twice in 2015: April 23-25, 2015 at Marquette University and again in the fall. Check Herman & Wallace's webite for further details.

http://www.gotpaindocs.com/gentfmrl_nurlga.htm

Tubbs et al.Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. March 2005 / Vol. 2 / No. 3 / Pages 335-338. Anatomical landmarks for the lumbar plexus on the posterior abdominal wall. http://thejns.org/doi/abs/10.3171/spi.2005.2.3.0335

Phillips EH. Surgical Endoscopy. January 1995, Volume 9, Issue 1, pp 16-21. Incidence of complications following laparoscopic hernioplasty

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00268-012-1657-2

Tsu W et al. World Journal of Surgery. October 2012, Volume 36, Issue 10, pp 2311-2319. Preservation Versus Division of Ilioinguinal Nerve on Open Mesh Repair of Inguinal Hernia: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Bischoff JM. Hernia. October 2012, Volume 16, Issue 5, pp 573-577. Does nerve identification during open inguinal herniorrhaphy reduce the risk of nerve damage and persistent pain?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ilioinguinal_nerve

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genitofemoral_nerve

Rab M, Ebmer And J, Dellon AL.. Anatomic variability of the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve: implications for the treatment of groin pain.

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery [2001, 108(6):1618-1623].

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cutaneous_innervation_of_the_lower_limbs

Cesmebasi et al (2014) Genitofemoral neuralgia: A review. Clinical Anatomy. Volume 28, Issue 1, pages 128–135, January 2015. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ca.22481/abstract

By accepting you will be accessing a service provided by a third-party external to https://www.hermanwallace.com/