Holly Tanner Short Interview Series - Episode 2 featuring Deb Gulbrandson

Holly Tanner and Deb Gulbrandson sat down to discuss the Osteoporosis Management Remote Course and why it is important for practitioners to recognize and know how to safely treat and manage osteoporosis patients in their practices.

Deb Gulbrandson shares the goal of the Osteoporosis Management remote course: "This course is based on the Meeks Method created by Sara Meeks, PT, MS, GCS...we have branched out to add information on sleep hygiene, exercise dosing, and basic nutrition for a person with low bone mass. Knowing how to recognize signs, screen for osteoporosis, and design an effective and safe program can be life-changing for these patients."

Join H&W at the Osteoporosis Management remote course, scheduled for September 18-19, 2021, to learn more about treating patients with osteoporosis.

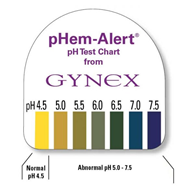

Many years ago a urology doctor shared the skill of testing vaginal pH as part of my pelvic floor exam. I’ve since used it to gather objective data around estrogen status, often finding elevated levels in post-partum, breastfeeding, and peri and post-menopausal women. When correlated with symptoms and visual skin changes this can be a helpful tool to both direct treatment and monitor treatment effectiveness.

To perform pH testing, place a pH strip into the distal vagina. Let it sit there for a few seconds to absorb vaginal moisture. Remove and record results. Any concerning changes in vaginal pH can be documented and reported back to your patient’s medical provider.

Here’s a quick tour through the research on vaginal pH. I hope you enjoy learning and consider adding vaginal pH testing to your clinical practice.

-Normal vaginal pH is considered to range between 4.0 and 5.0 in menstruating women (Garcia-Closas)

-Intervaginal pH does not vary between vaginal location (proximal, mid, distal)

-Clinician test vs self-test results vary slightly but not significantly (Ferris)

-Low serum estradiol levels are associated with high vaginal pH values

-Vaginal pH of 4.5 is indicative of premenopausal estradiol levels and the absence of bacterial overgrowth

-Vaginal pH of 5.0 to 6.5 may indicate either estrogen changes or bacterial overgrowth, a culture may be warranted

-Vaginal pH of 6.0 to 7.5 is strongly suggestive of menopause

-Vaginal pH measurements can be helpful in determining the efficacy of treatment with vaginal estrogen (Caillouette)

-Vaginal pH levels (high) were as sensitive as blood serum FSH levels in the detection of menopause status (Roy) and (Panda)

-Understanding of the vaginal microbiome and its effect on vaginal pH continues to evolve

-“Although lactic acid (produced by Lactobacillus) is the primary acid in normal vaginal secretions, other organic acids such as acetic, mydriatic, and linoleic acid are also normally found in vaginal fluid. Some healthy women actually lack vaginal Lactobacilli, but their vaginal pH is in the normal (moderately acidic) range, and other lactic acid-producing bacteria, such as Atopobium, Megasphaera, and/or Leptotrichia species, are present.”

-Lactic acid is also a byproduct of anaerobic glucose metabolism within the cells of the vaginal mucosa

-The summation of vaginal pH is determined by both the vaginal mucosal metabolism (which is influenced by estrogen) and the vaginal microbiome, both of which are unique to each female

-Vaginal pH is around 5 in newborns, before colonization from microbes, rises to neutral range by 6 weeks of life, and falls when puberty ushers in an increase in estrogen

-Normal vaginal pH helps to keep optimal inflammatory responses and skin barrier functions in vaginal and vulvar skin. Elevated pH in menopause leads to susceptibility to vulvar contact dermatitis

-Topical application to the menopausal vagina restores surface pH and lowers infection risk

-Candida infections do not alter vaginal pH

-STI via chlamydia, gonorrhea, or trichomonas as well as bacterial vaginosis may cause elevations in vaginal pH (Linhares)

- “Detection of HPV was positively associated with vaginal pH, mainly in women < 35 years. Elevated vaginal pH was associated with 30% greater risk of infection with multiple HPV types and with LSIL (low-grade intraepithelial lesions), predominantly in women younger than 35 and 65+ years of age. Detection of C. trachomatis DNA was associated with increased vaginal pH in women < 25 years” (Clarke)

-pH self-testing during pregnancy and treatment of underlying infections positively impacted preterm birth rates (Holyoke and Saling)

-The microbiome in humans is generally >70% Lactobacilli, where other mammals have 1% or less

-Average pH of 21 non-human mammals is 5.4 to 7.8

-Authors propose that the high level of starch in human diets contributes to increased levels of vaginal glycogen which in turn proliferates lactobacilli…continued research will contribute to our collective knowledge base (Miller)

-Vaginal microbiome variability may have an effect on fertility (Xu)

-Douching with an over-the-counter lactic acid containing douche: did not significantly affect vaginal pH or microbiome composition and may promote candida infections (van der Veer)

|

Solution |

pH |

|

Gastric acid |

1.5-2.0 |

|

Vinegar |

2.9 |

|

Orange juice |

3.5 |

|

Beer |

4.5 |

|

4.5 |

|

|

Skin surface moisture |

4.0-5.5 |

|

Milk |

6.5 |

|

Pure water |

7.0 |

|

Saliva |

6.5-7.4 |

|

Semen |

7.2-8.0 |

|

Blood |

7.3-7.5 |

|

Seawater |

7.7-8.3 |

|

Sodium bicarbonate |

8.4 |

|

Hand soap solution |

9.0-10.0 |

|

Bleach |

12.5 |

Linhares. Vaginal pH and Lactobacilli. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011.

References:

Caillouette, J. C., Sharp Jr, C. F., Zimmerman, G. J., & Roy, S. (1997). Vaginal pH as a marker for bacterial pathogens and menopausal status. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 176(6), 1270-1277.

Clarke, M. A., Rodriguez, A. C., Gage, J. C., Herrero, R., Hildesheim, A., Wacholder, S., ... & Schiffman, M. (2012). A large, population-based study of age-related associations between vaginal pH and human papillomavirus infection. BMC infectious diseases, 12(1), 1-9.

Ferris, D. G., Francis, S. L., Dickman, E. D., Miler-Miles, K., Waller, J. L., & McClendon, N. (2006). Variability of vaginal pH determination by patients and clinicians. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 19(4), 368-373.

García-Closas, M., Herrero, R., Bratti, C., Hildesheim, A., Sherman, M. E., Morera, L. A., & Schiffman, M. (1999). Epidemiologic determinants of vaginal pH. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 180(5), 1060-1066.

Hoyme, U. B., & Saling, E. (2004). Efficient prematurity prevention is possible by pH-self measurement and immediate therapy of threatening ascending infection.

Linhares, I. M., Summers, P. R., Larsen, B., Giraldo, P. C., & Witkin, S. S. (2011). Contemporary perspectives on vaginal pH and lactobacilli. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 204(2), 120-e1.

Miller, E. A., Beasley, D. E., Dunn, R. R., & Archie, E. A. (2016). Lactobacilli dominance and vaginal pH: Why is the human vaginal microbiome unique?. Frontiers in microbiology, 7, 1936.

Panda, S., Das, A., Santa Singh, A., & Pala, S. (2014). Vaginal pH: A marker for menopause. Journal of mid-life health, 5(1), 34.

Roy, S., Caillouette, J. C., Roy, T., & Faden, J. S. (2004). Vaginal pH is similar to follicle-stimulating hormone for menopause diagnosis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 190(5), 1272-1277.

Xu, J., Bian, G., Zheng, M., Lu, G., Chan, W. Y., Li, W., ... & Du, Y. (2020). Fertility factors affect the vaginal microbiome in women of reproductive age. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 83(4), e13220.

Van Der Veer, C., Bruisten, S. M., Van Houdt, R., Matser, A. A., Tachedjian, G., van de Wijgert, J. H. H. M., ... & van der Helm, J. J. (2019). Effects of an over-the-counter lactic-acid containing intra-vaginal douching product on the vaginal microbiota. BMC microbiology, 19(1), 1-13.

*Citations are noted at the end of each article summary

This product was recommended by S. Roy for accurate testing:

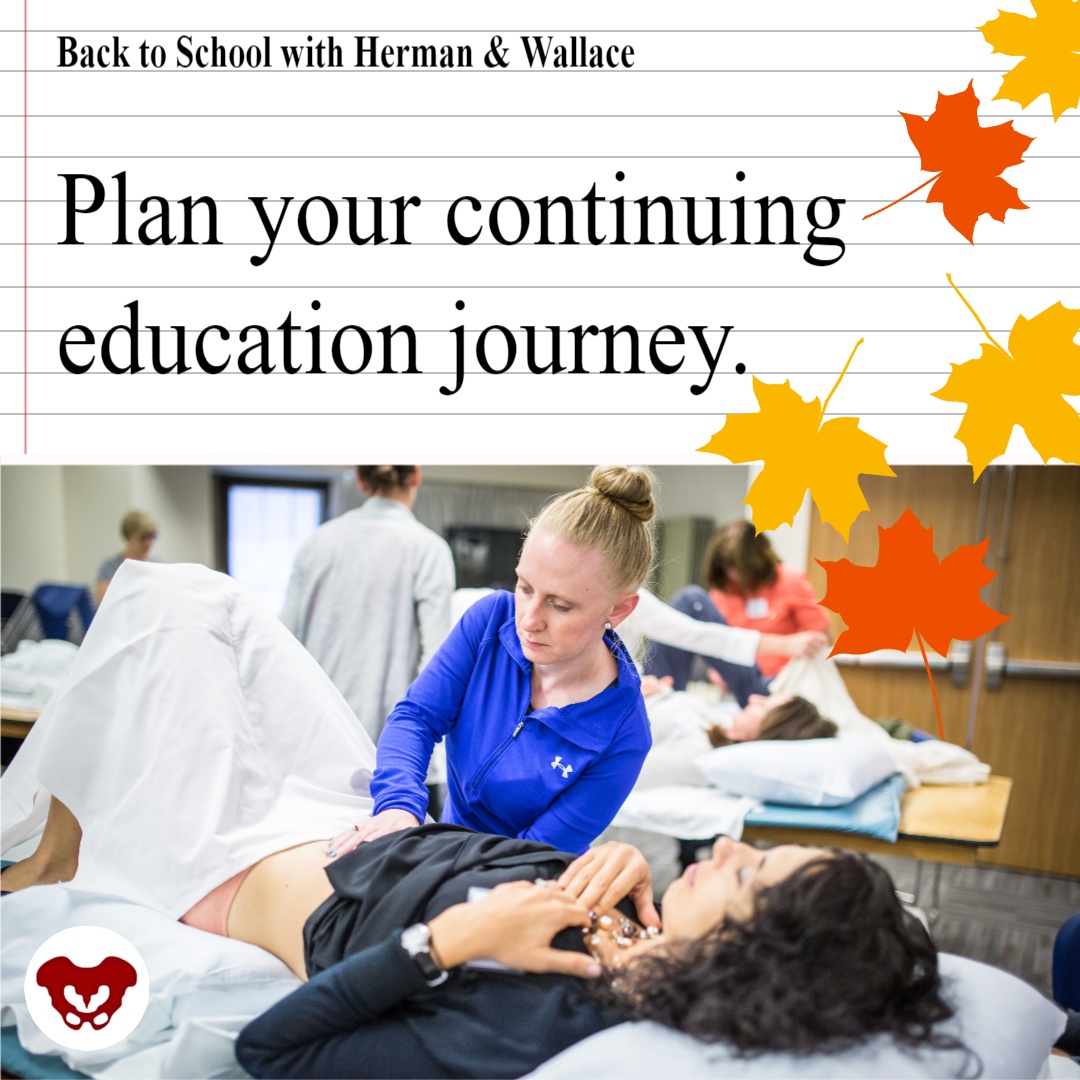

It’s back-to-school time for Herman & Wallace! H&W courses are provided in one of two formats: remote courses, and satellite lab courses.

Our team here at H&W has been working hard to schedule courses throughout the rest of this year and into 2022. If you are looking for the perfect course, then check the course catalog. We are adding course events to the schedule every week. There are several brand new course options on the schedule.

New Satellite Lab Courses:

Satellite lab courses allow participants and teaching assistants to gather in small groups to view lectures and practice hands-on labs. The satellite lab course also has an option where you can register with a partner and attend remotely together as a Self-Hosted Satellite.

- Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging - Orthopedic Topics November 12-13, 2021

- Rehabilitative Ultrasound Imaging - Women's Health and Orthopedic Topics November 12—14, 2021

- Biofeedback for Pelvic Muscle Dysfunction December 4-5, 2021

New Remote Courses:

Remote courses allow registrants to attend entirely from home or another safe location. Registrants in remote courses can often attend the course "solo" and do not need to find a partner or small group. In terms of COVID-19, remote courses are our safest option for those who want to eliminate their potential exposure to other registrants.

- Shockwave Treatment: Therapeutic Interventions in Pelvic Health & Demystifying the Research September 12, 2021

- Oncology of the Pelvic Floor Level 2A October 2-3, 2021

- Weightlifting and Functional Fitness Athletes October 16, 2021

- Transgender Patients: Pelvic Health and Orthopedic Considerations October 30, 2021

- Fertility Considerations for the Pelvic Therapist November 7, 2021

- Doula Services and Pelvic Rehab Therapy December 4, 2021

- Pudendal Dysfunction: The Physician's Perspective January 9, 2022

- Perinatal Mental Health: The Role of Pelvic Rehab Therapist February 5, 2022

Don't see the course you are looking for? Check out the full course list on the Herman & Wallace Continuing Education Courses page.

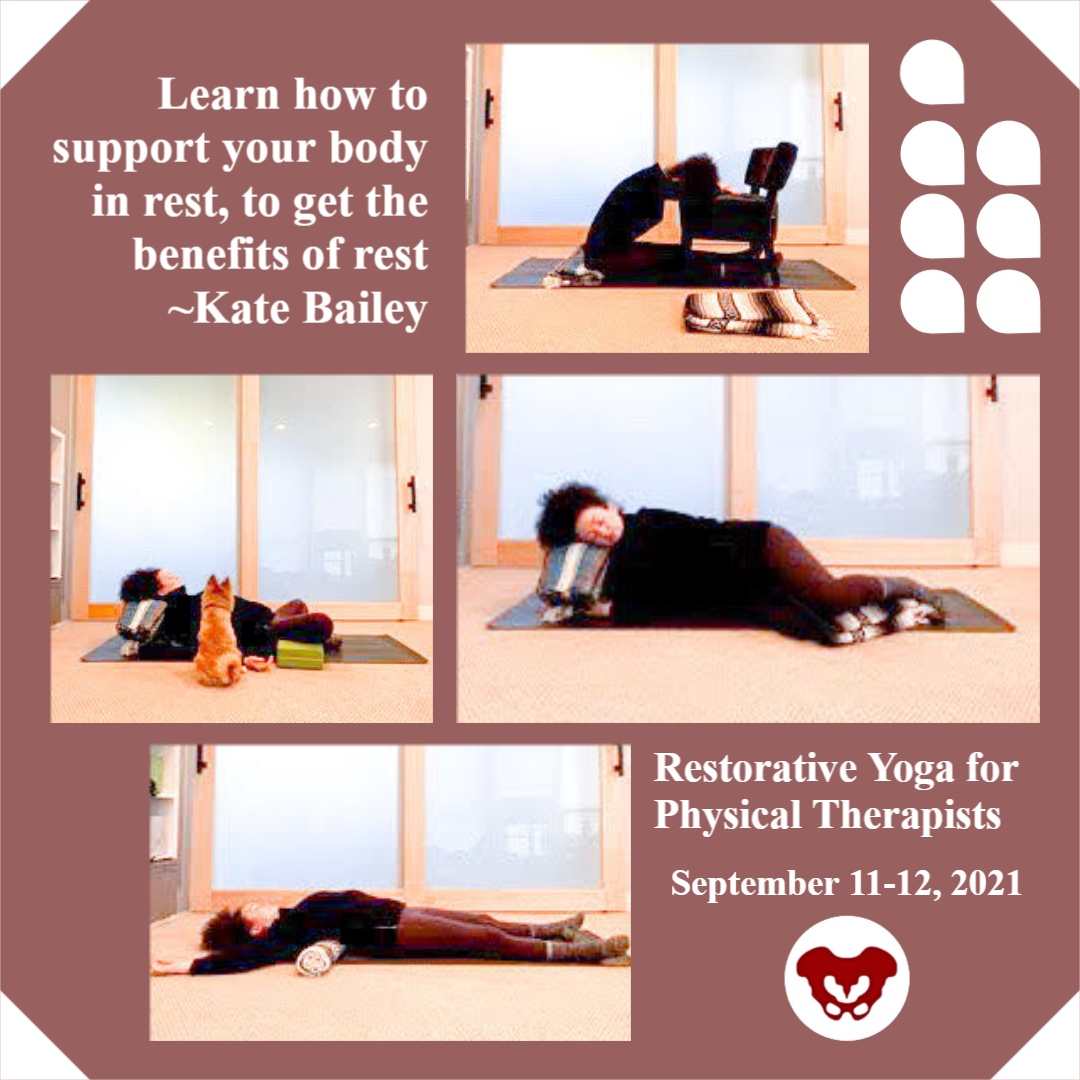

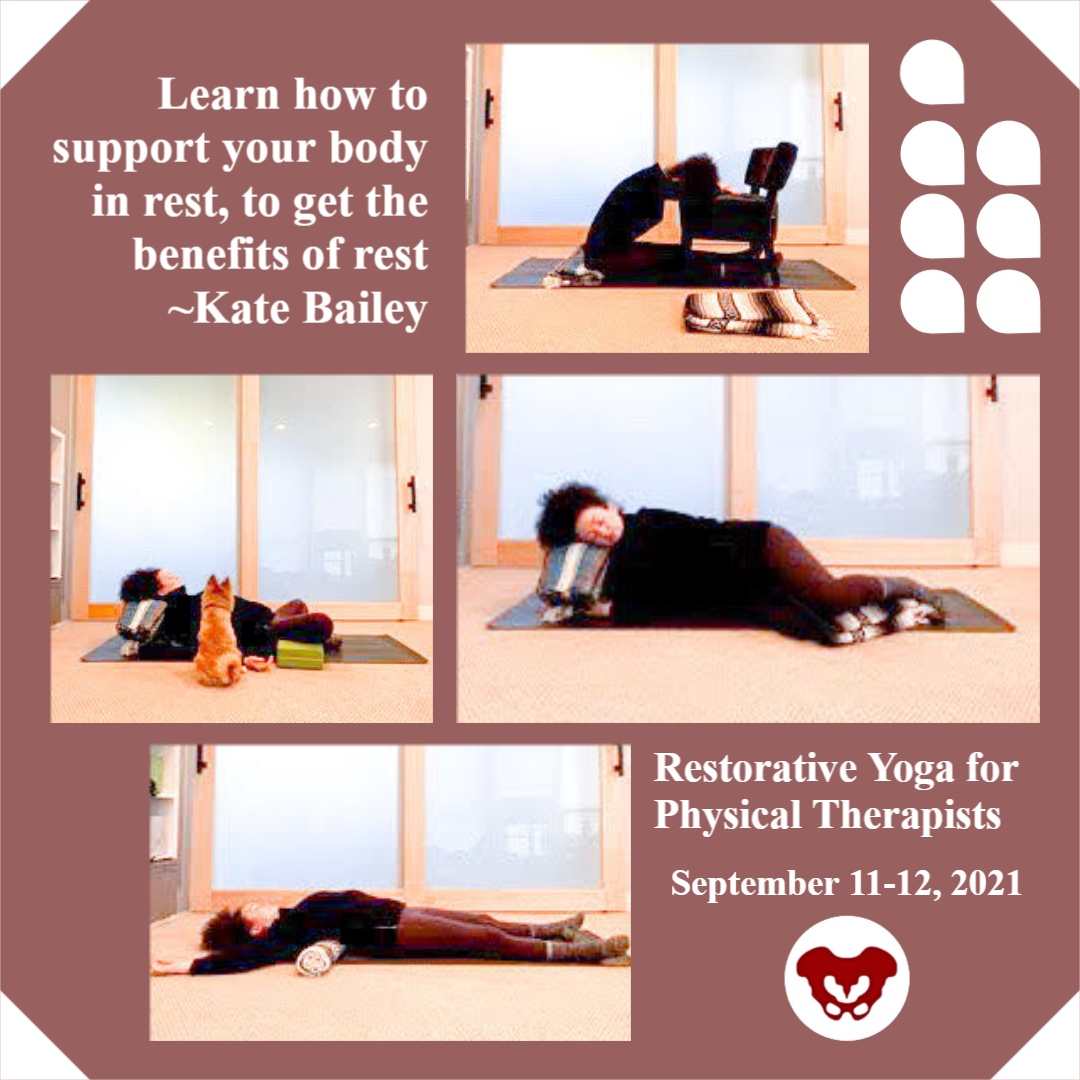

This week The Pelvic Rehab Report sat down with Kate Bailey, PT, DPT, MS, E-RYT 500, YACEP, Y4C, CPI to discuss her career as a physical therapist and upcoming course, Restorative Yoga for Physical Therapists, scheduled for September 11-12, 2021. Kate’s course combines live discussions and labs with pre-recorded lectures and practices that will be the basis for experiencing and integrating restorative yoga into physical therapy practice. Kate brings over 15 years of teaching movement experience to her physical therapy practice with specialties in Pilates and yoga with a focus on alignment and embodiment.

Who are you? Describe your clinical practice.

My name is Kate Bailey. I own a private practice in Seattle that focuses on pelvic health for all genders and ages. I work under a trauma-informed model where patient self-advocacy and embodiment are a priority. My dog, Elly, assists in my practice by providing a cute face and some calming doggy energy. My patients often joke that they come to see her just as much as to see me, which I think is great. In addition to being a physical therapist, I’ve been teaching Pilates for nearly 20 years and yoga for over 10. They are both big parts of my practice philosophy and my own personal movement practice

What books or articles have impacted you as a clinician?

I have a diverse library of Buddhist philosophy, emotional intelligence, trauma psychology, human behavior, breathwork/yoga, and sociology and, of course, a bunch of physical therapy pelvic floor books. I also love a children’s book on emotional regulation or inclusion, even for adults. One of my favorite finds is the Spot series that gives kiddos different ways to use their hands to help deal with different emotions. I’ve used it for adults who need physical self-soothing options. There are so many, and I find that it's the amalgamation of information that really impacts my practice the most.

How did you get involved in the pelvic rehabilitation field?

I have a deep interest in the human experience and how culture and dissociation create mass-disembodiment and how hands-on work can be profound in how we experience our body. Pelvic rehab allowed me the opportunity to work more closely with people on areas that bring up the most shame, disembodiment, and trauma, and therefore have some pretty amazing possibilities to make an impact not only in their lives but how they act in culture. In many ways, I see my work in pelvic rehab as a point of personal activism in creating a more embodied, empowered, and powerful culture.

What has your educational journey as a pelvic rehab therapist looked like?

I knew I wanted to go into pelvic health from my second year in PT school. I’ve always been at bit…well, let’s call it driven. I did an internship with great therapists in Austin and then only considered full-time pelvic floor positions once licensed. I took as many courses as I could handle in my first couple years of practice, which worked well for me, but understandably is not the right path for all those entering this field for a number of reasons. I went through the foundational series, and then into visceral work as well as continued my yoga and Pilates studies. I continued my education in trauma and emotional intelligence which is both a personal and professional practice. I found that a blend of online coursework and in-person kept me satisfied with my educational appetite.

What made you want to create your course, Restorative Yoga for Physical Therapists?

I was a yoga teacher long before I became a PT. When I found my way into the specialty of pelvic floor physical therapy, this particular part of my yoga teaching became incredibly useful for patients who had high anxiety, high stress, and difficulty with relaxation and/or meditation. This course was a way for me to share some of my knowledge of restorative yoga with the community of health care providers, where it could not only be used as a means of helping patients, but also as a means to start valuing rest as a primary component of wellbeing.

What need does your course fill in the field of pelvic rehabilitation?

Learning about yoga as a full practice and understanding that it has many components is very useful in deciding which component would be a good match for a pelvic health patient. Is it strengthening from an active practice? Is it meditation or pranayama (breath manipulation)? Or is it supported rest? This particular course focuses on the lesser-known aspects of the yoga platform: breath, restorative practice, and a bit of meditation. I have clients all the time struggle with meditation because their nervous systems aren’t ready for it. So we look at breathing and restorative yoga both as independent alternatives, but also as a way to get closer to meditation. Learning how to help people rest, the different postures, how to prop, and how to dose is an important component of this class. As a bonus, giving the clinicians another skill for their own rest practice can be useful when feeling tired, overwhelmed, or burned out. All this under a trauma-informed, neuro-regulation-focused model is a lovely way to deepen one’s physical therapy practice.

What demographic, would benefit from your course?

People who are stressed out or who work with people who are stressed out. In particular, clinicians who work with people who have pelvic pain or overactivity in their pelvic floors.

What patient population do you find most rewarding in treating and why?

I love working with female-identifying patients that struggle with sexual health or those who are hypermobile and trying to figure out movement that feels good. I love working with all genders generally and do so regularly. There’s nothing quite like helping a male-identifying patient find embodiment and understanding of their pelvis in a new way. I think for me, working to dismantle female normative structures for those identifying as female, particularly in the realm of sexual health feels inspiring to me because it combines physical, emotional, spiritual health with going against the cultural standards of how those identifying as women fit into society, and being able to sit with the trauma of all types that so many people face.

What do you find is the most useful resource for your practice?

A pelvic floor model is great. The most important part of my practice is a conversation about consent, not only for internal work but for everything I offer during visits and also for patients to understand that they can give or retract consent with any medical provider for just about any service. Emergency procedures are a smidge different, but I hope my patients walk away with the understanding that the medical community is here to serve their embodied experience. My newest favorite resource is a series of metal prints that depict the emotional intelligence grid used in the RULER syllabus. I have a magnet that patients can use to identify how they are feeling and help develop their language for emotional and then somatic or interoceptive knowledge.

What has been your favorite Herman & Wallace Course and why?

There was nothing quite like PF1. I don’t think I’ll ever forget it. The instructors were Stacey Futterman Tauriello and Susannah Haarmann. I was still in grad school prepping for my internship and ended up being the model for labs which falls squarely in line with my upbringing as a dancer who wanted to understand everything from the inside out. It was a challenging weekend on pretty much every level. I went through phases of dissociation and total connection. It made me realize that my decision to enter health care after having a career in movement was the right one.

What lesson have you learned from a course, instructor, colleague, or mentor that has stayed with you?

Meet the patient where they are at first and validate that they live in an incredibly intelligent body. I think sometimes it’s so exciting to see the potential that patients have because, as clinicians, we’ve seen the progress of others. In yoga, there is a practice of the beginner’s mind. It asks the student to sit with an empty cup of knowledge and experience each practice with the curiosity of someone just being introduced to yoga. I have knowledge that may be helpful to patients. Patients have so much knowledge of their own body from their life experiences, some of which are conscious and so much of which is subconscious. The fun part is seeing how my experience and their experience match (or don’t sometimes) to then assess how to craft the care plan.

If you could get a message out to other clinicians about pelvic rehab what would it be?

That it's so much more than pelvic rehab. We get to talk to people about things that aren’t talked about and normalize the human experience. Pelvic rehab gives safety to patients to experience their bodies in all the sensations that come from having a nervous system: from sadness to joy to relief to fear. It's all in there and when we learn about those sensations from pelvic rehab, my hope is that it can flood into other areas of life.

What is in store for you in the future as a clinician?

Refining, learning, and seeing what else comes. Hoping to publish a book of cartoon organs shortly. But most importantly to create a safe space for patients to feel cared for and supported in my corner of Seattle.

Kate Bailey (She/Her)

Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy

Yoga & Pilates

The pelvis contains several parallel nerve groups. One of which is the lumbar plexus and its sensitive branches. This nerve web arises from the anterior rami of lumbar spinal nerves L1 to L4 and T12 from the thoracic spinal nerve.

Nari Clemons instructs the remote course, Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment, which addresses assessments for the contributory nerves from the lumbar plexus, anatomy, differential diagnosis, and objective findings for specific nerves of the lumbar plexus. This advanced-level course also provides twelve lab techniques for manually treating the nerves of the lumbar plexus.

Peripheral lumbar plexus nerves included in this course are Iliohypogastric, Ilioinguinal, Genitofemoral, Lateral Femoral Cutaneous, Femoral, and Obturator Nerves. These nerves are vital for the functioning of the lower extremities, including maintaining the ability to extend the knee, flex the hip, and adduct the thigh.

When a nerve becomes restricted, it disrupts the nerve signal allowing for symptoms to present as possible pain, weakness, numbness, or tingling. The lumbar plexus is vulnerable to injury when its bony protection, the pelvis, is compromised. Based on research from Anthony Chiodo, retroperitoneal hemorrhage, superior ramus fractures, traction, and penetrating injuries all can cause injury to the lumbar plexus. There are also a variety of conditions such as herniated disc, spinal arthritis, repetitive activities, and even poor posture that can lead to lumbar nerve pain, or a pinched nerve.

Nari explains in the Lumbar Course anatomy lecture that, "Dura matter covers the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerve. If you have tension in the peripheral nerves it can cause tension in the central nervous system and vice versa. When working with the nerves it is important to down-train the nervous system. Because the nerves run continuously it is always important to down-train and practice pain theory." She continues to explain that "The osteopathic approach to the fascial system of the peripheral nerve does not have a grounding in scientific research and is based on clinical experience from individuals using peripheral nerve palpation as a method for the evaluation of the nerve's function."

This means that there is not a singular proven technique that is more helpful than another when addressing nerves. The Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment course is essentially a melting pot that pulls from multiple studies and research. The evidence-based, step-by-step approach to treating the lumbar nerve includes

- Decompression to clear the path of the nerve and potential sites of restriction.

- Fascial techniques, just like those that we use with the other fascia of the body.

- Slacking the nerve towards its origin to create ease.

- Gliding the nerve in a pain-free manner.

- Strengthening the weakened muscles.

Differential diagnosis and treatment of these lumbar plexus nerves can allow patients to return to full daily function. Learn manual assessment and treatment techniques from Nari Clemons in the next Lumbar Nerve Manual Assessment and Treatment remote course, scheduled for September 11-12, 2021.

Osteoporosis is known to be a painless, progressive condition that leads to a weakening of the bones and can lead to a higher risk for broken bones. The upcoming remote course, Osteoporosis Management, scheduled for September 18-19, 2021, will discuss the scope of problems, specific tests for evaluating patients, appropriate safe exercises and dosing, and basic nutrition.

H&W faculty member Deb Gulbrandson recommends using the National Osteoporosis Foundation database for a resource and emphasizes the prevalence of osteoporosis is in a past interview for the Pelvic Rehab Report. "Approximately 1 in 2 women over the age of 50 will suffer a fragility fracture in their lifetime...According to the US Census Bureau, there are 72 million baby boomers (age 51-72) in 2019. Currently, over 10 million Americans have osteoporosis and 44 million have low bone mass."

A well-known consequence of osteoporosis is the increased risk of fragility fractures. A fragility fracture is often the first sign of osteoporosis and can be the cause of pain, disability, and quality of life for the patient. Research by Marsha van Oostwaard provided data that suggests about 13 percent of men and 40 percent of women with osteoporosis will experience a fragility fracture in their lifetime. Men also have a higher rate of mortality from fragility fractures relative to women (1).

The International Osteoporosis Foundation reports that patients who have suffered from a fragility fracture are at a high risk of experiencing secondary fractures, especially within two years of the initial fracture. Fragility fractures can result in osteoporotic patients from events that would not elicit an injury in a healthy adult. These events can include falling from a standing position and other low-energy traumas.

Fragility fractures are characterized by low bone mineral density and have an increased incidence with age (2). The risk of a fragility fracture is also influenced by bone geometry and microstructure. The most serious fracture sites are at the hip and vertebrae, but fractures can occur also on the ribs and other locations. Healthcare practitioners can assist patients in adapting lifestyle factors including exercise, sleep positions, and nutrition with the aim of helping prevent falls from occurring.

Deb Gulbrandson shares the goal of the Osteoporosis Management remote course: "This course is based on the Meeks Method created by Sara Meeks, PT, MS, GCS...we have branched out to add information on sleep hygiene, exercise dosing, and basic nutrition for a person with low bone mass. Knowing how to recognize signs, screen for osteoporosis, and design an effective and safe program can be life-changing for these patients."

Join H&W at the Osteoporosis Management remote course, scheduled for September 18-19, 2021, to learn more about treating patients with osteoporosis.

- Fragility Fracture Nursing: Holistic Care and Management of the Orthogeriatric Patient [Internet]. Marsha van Oostwaard. Hertz K, Santy-Tomlinson J. Springer; 2018.

- The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Kanis, J.A., et al. Osteoporos Int, 2001. 12(5): p. 417-27.

The hip flexor muscles include the Iliopsoas group (Psoas Major, Psoas Minor, and Iliacus), Rectus Femoris, Pectineus, Gracillis, Tensor Fascia Latae, and Sartorius. When the hip flexors are tight it can cause tension on the pelvic floor. This can pull on the lower back and pelvis as well as change the orientation of the hip socket, lead to knee pain, foot pain, bladder leakage, prolapse, and so much more. The ramifications of iliacus and iliopsoas dysfunctions are discussed in Ramona Horton's visceral course series:

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Gastrointestinal System

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia - The Urinary System

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia - The Reproductive System

You can also learn about this in a contemporary and evidence-based model with Steve Dischiavi in his Sacroiliac Joint Current Concepts and Athletes & Pelvic Rehabilitation remote courses.

A common issue with the iliacus and hip flexors is that they can shorten over time due to a lack of stretching or a sedentary lifestyle. When this happens, the muscle adapts by becoming short, dense, and inflexible and can have trouble returning to its previous resting length. A muscle that resides in this chronic contraction can become ischemic, develop trigger points, and distort movement in the body.

If you are treating patients with pain in their lower abdomen, sacroiliac joint, or that wraps around the lower back and buttocks, it could be because the hip flexors are tight. Traditional testing performed by medical practitioners tends to come back negative as many tests do not evaluate soft tissue issues. The best way to diagnose these concerns is through assessment with skilled palpation and structural evaluation.

One assessment test used for the iliopsoas is discussed in the Athletes & Pelvic Rehabilitation course. This is the Thomas Test which measures the flexibility of the hip flexors. In this test, the patient is supine while flexing the unaffected, contralateral leg at the hip until lumbar lordosis disappears. The length of the iliopsoas is determined by the angle of hip flexion displayed by the patient. The test is positive when the patient is unable to keep their lower back and sacrum against the table, the hip has a posterior tilt (or hip extension) greater than 15°, or the knee is unable to meet more than 80° flexion. A positive test indicates a decrease in flexibility iliopsoas muscles.

Treatment plans for the iliacus and hip flexors include stretching. An example includes the hip extension stretch or other active isolated stretches. Manual therapy, including trigger point release, can be used in conjunction with stretching to help muscle adhesion and release muscle tension. As with all treatment, the practitioner should discuss the risks, benefits, and treatment options, and obtain consent with patients. Prior to proceeding with manual therapy treatment make sure to establish a pain scale, assess the patient's range of motion and strength, and (if needed) perform the appropriate neurologic testing.

To learn more about manual therapy options for the visceral fascia, join Ramon Horton in her Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia Satellite Lab Course Series (multiple satellite locations available):

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Gastrointestinal System - October 15-17, 2021

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Urinary System- September 17-19, 2021

- Mobilization of the Visceral Fascia: The Reproductive System - October 1-3, 2021

To learn more about treatment philosophies for the pelvis and pelvic floor and global considerations of how these structures contribute to human movement you can join Steve Dischiavi:

- Athletes & Pelvic Rehabilitation Remote Course - September 18-19, 2021

- Sacroiliac Joint Current Concepts Remote Course - August 21, 2021

The world needs more clinicians who can treat pelvic pain, pelvic organ prolapse, urinary incontinence, diastasis recti, and the many other conditions that constitute pelvic floor/pelvic girdle dysfunction. Most clinicians who specialize in pelvic rehabilitation are Physical Therapists (PT) or Occupational Therapists (OT), though other licenses also allow you to work with patients who have pelvic floor dysfunction. Many doctors, nurses, and internationally licensed medical professionals are beginning to explore the field of pelvic rehabilitation.

In an interview for the Pelvic Rehab Report, faculty and instructor Tiffany Ellsworth Lee MA, OTR, BCB-PMD, PRPC, shared that "Occupational therapists wishing to pursue pelvic floor have a few options. The first thing is to find a pelvic floor clinical setting...or check to see if they can start a women's health program with a strong focus on the pelvic floor. OTs quite often do not start out in pelvic health directly after school. Since this is a newer area as compared to other certifications such as the NDT and PNF, it takes a little bit of research, time, and effort to find one’s exact niche. To get started, an OT should seek out courses that teach the basics of bladder and bowel management. It is important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the bladder, bowel, and sexual systems."

Once you have a license to practice, you can start learning to specialize in pelvic rehabilitation. The best place to start is with the H&W Pelvic Floor Level 1 satellite lab course, which offers immediately applicable clinical skills for evaluating and treating urinary incontinence or the musculoskeletal components of urogynecologic pain syndromes. Most practitioners who take Pelvic Floor 1 return to study in the next courses in the series.

You can learn all about the colorectal system, and how to treat conditions such as coccyx pain, pudendal neuralgia, and male pelvic pain in the Pelvic Floor 2A course, and in Pelvic Floor 2B you can expand your knowledge in topics such as movement assessment and re-training, prolapse, and pelvic pain. Then in the Pelvic Floor Capstone course, the final advanced course, you dive deep into topics such as hormones and their influence on conditions, surgeries and recovery, and skilled manual therapy techniques. Once you know your patient demographic, you can check out our growing list of specialty courses that include series topics including yoga, oncology, pregnancy, fascial mobilization, and much more.

Once you have gained experience in the field, you may consider sitting for the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification (PRPC). This certification recognizes expertise in pelvic rehabilitation for patients of all genders throughout the lifecycle. To be eligible to sit for the exam, applicants must have completed 2000 licensed hours of direct pelvic patient care in the past eight years, 500 of which must have been in the last two years.

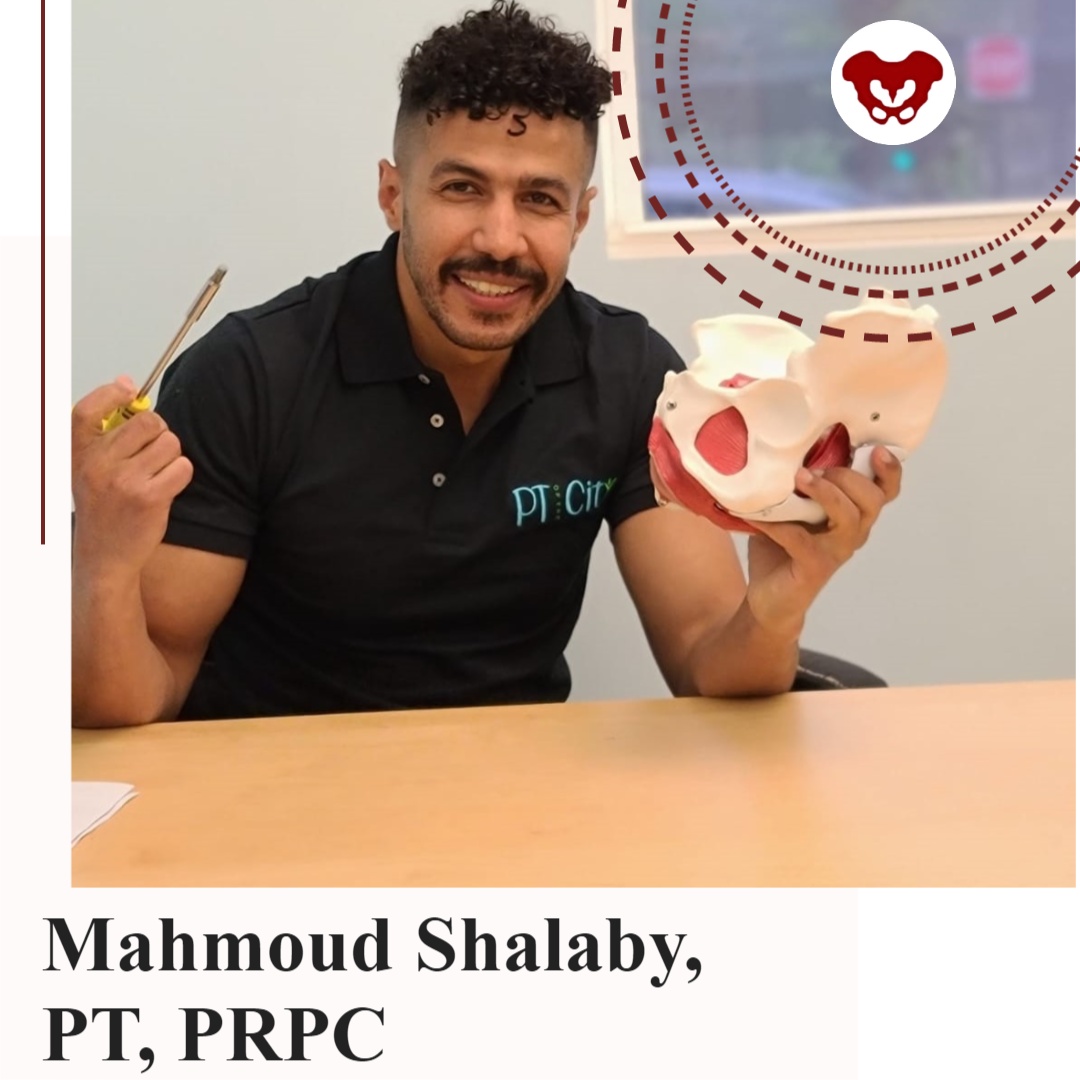

The following is our interview with Mahmoud Shalaby, PT, MS, DPT, PRPC. Mahmoud recently passed the Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner Certification (PRPC) exam. He practices at PT of The City in Brooklyn, NY, and is a Teaching Assistant for local New York satellite courses with H&W. Mahmoud was kind enough to share some thoughts about his career with us. Thank you, Mahmoud - and congratulations on receiving your PRPC!

In 2016, I was offered the chance to shadow a senior PT who specialized in pelvic rehab. This specialty was mysterious for me. I didn't think that there was much we could offer to patients with pelvic issues like incontinence, prolapse, IC, and such until I started to treat them. Once I commenced learning more, it never ends.

There is always more to discover and I've always been impressed with the role of physical therapists in assessing and treating pelvic issues. I continue to be very excited to learn more and to develop my experience while further participating in studies to improve my skills and tools in improving people's quality of life.

Herman & Wallace institute has always been my partner in success, they knew how to get me on the track and impressively integrate all resources across body systems to make me confident and skillful to help patients.

When I`ve attended the courses at Herman & Wallace, I have looked at their great Pelvic Rehab certification and immediately I`ve decided to become a certified pelvic rehab specialist for many reasons. To begin with, we must keep high standards to provide such a specific skilled service, in addition to improving my skills, knowledge, and quality to help patients. There are a lot of people suffering from those issues, they either do not know how to address those issues or they do not know where to go.

In particular cultures and religions, the gender of the doctor matters, especially when it comes to sensitive topics, and I am proud to be among the two or three male certified pelvic rehab specialists across the country and I am always happy to get the patients comfortable and confident to be able to address their issues and help them reach their goals.

Working as a teaching assistant at Herman & Wallace is a great opportunity to learn more and explore how newbie therapists think, and help them to see the great skills and tools at this specialty.

As pelvic rehab specialists, we have a great responsibility to raise awareness and educate the community and let them know that we are here for them.

Kate Bailey, PT, DPT, MS, E-RYT 500, YACEP, Y4C, CPI curated and instructs the remote course on Restorative Yoga for Physical Therapists, which is scheduled for September 11-12, 2021. Kate brings over 15 years of teaching movement experience to her physical therapy practice with specialties in Pilates and yoga with a focus on alignment and embodiment. Kate’s pilates background was unusual as it followed a multi-lineage price apprenticeship model that included the study of complementary movement methodologies such as the Franklin Method, Feldenkrais, and Gyrotonics®. Building on her Pilates teaching experience, Kate began an in-depth study of yoga, training with renown teachers of the vinyasa and Iyengar traditions. She held a private practice teaching movement prior to transitioning into physical therapy and relocating to Seattle.

Without a doubt, these past couple of years have been tough with this global pandemic of a virus that caused major shifts in how we work, play, learn and socialize. Wherever you live on this planet, it is nearly impossible not to have been affected by the stress and trauma that the Covid-19 virus has created. Just like with any other stressor, the first step of management is recognition. Check, done.

Step two involves making conscious choices about how we want to live. This is where we have some options, including self-care. “Self-care” is one of my least favorite phrases. Not because at its core, self-care is not important. But because it's another thing on an overflowing to-do list and can create even more of a sense of imbalance, lack of accomplishment, and self-defeat. Yet, learning how to manage stress is a skill we all need: individually and communally.

However, there is a step before stress management that we need to address first. Interoception, defined by Porges, Ph.D., is the process that describes both conscious feelings and unconscious monitoring of bodily processes by the nervous system. As a clinician, this is a key aspect of every single patient care plan. I am a big fan of embodied decision making, and yet our somatic intelligence (or interoceptive skills) is widely underdeveloped.

Just as emotional intelligence is getting some wonderful development, through the work of researchers and educators like Marc Brackett, Ph.D. of Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence, our wellbeing and access to wellness are dependent on our ability to understand the sensations and signals throughout our body and then make a choice. This is important since you can’t make an embodied choice (step 2) before you have the data (step 1 - interoception). An example would be to imagine if you never felt the sensation of hunger, or the ‘hangry’ feeling when it’s been too long since the last boost of nourishment…how would you determine that you are hungry?

So, what to do? Many of us (clinicians and patients alike) live in a world full of overstimulation, productivity requirements, and constant stress. To develop interoception, finding little periods of stillness can be really useful. In yoga, there is a dedicated practice called pratyahara. Translated from Sanskrit to English as ‘withdrawal of the senses.’ The senses, in this case, includes all the sense organs: sight, smell, sound, touch, taste, movement (vestibular), and spatial placement (proprioception). Traditionally this is an aspect of meditation.

In my experience as a yoga teacher and physical therapist, I find this practice more accessible in the restorative yoga practice. It can take some graded exposure, but at the heart of the restorative yoga practice is stillness, darkness, silence, and support from props so that the body doesn’t have to do anything. These are also the essential components described by Herbert Benson, MD in his work on the Relaxation Response. In his work, he showed the relaxation response to be effective in decreasing heart and respiration rate triggering the benefits of the vagal nerve; which we are learning has so much to do with our ability to neuroregulate and participate in individual and communal stress management.

Restorative yoga is a practice of wakefully resting. Immordino-Yang et al, studied the brain in functional MRI when individuals were wakefully resting. The study found that during wakeful rest (without a meditative component where the brain has a task of concentration) the brain goes into a mode of neural processing called default mode. In default mode, the brain supports memory recall, imagining the future, and developing socio-emotional intelligence. In relationship to stress management, this is so important because it re-centers us, and allows for connection for even more neuroregulation.

For my patients, I often joke about lying on the floor. Really, it is not a joke at all. Lying on the floor for 15 minutes is savasana. Savasana is a wakeful resting and a practice of relaxation response. It seems easy: you always have access to a floor. You don’t need anything fancy. Aside from the neuroregulatory benefits of rest, savasana also gives the postural muscles a break. It allows the hip flexors to re-lengthen and the cervicothoracic junction to realign.

It is pretty great, and really accessible for most people. For those who are not comfortable flat, that’s where the props used in restorative yoga come into play. As physical and occupational therapists, we are so well primed to help people learn how to support their bodies in rest to get the benefits of rest.

Burnout, the Secret to unlocking the stress cycle by Emily Nagoski, Ph.D. and Amelia Nagoski, DMA

Polyvagal Theory, Stephen W Porges, PhD

Immordino-Yang et al. - Perspectives on Psychological Science - 2012

The Relaxation Response by Herbert Benson, MD, and Miriam Z Klipper