Pelvic rehabilitation professionals know that working with athletes requires a unique lens—and when your client is both an athlete and navigating the perinatal period, the clinical complexity deepens.

That’s why Herman & Wallace is excited to announce the High Intensity Perinatal Athletics Practicum, coming to Somerset, NJ on September 27–28, 2025. This two-day course is built for pelvic rehab practitioners who want to elevate their skills in evaluating and treating pregnant and postpartum individuals engaging in high-intensity interval training (HIIT), including activities like weightlifting, gymnastics, plyometrics, and running.

The practicum blends pre-course videos, targeted in-person lectures, and hands-on movement labs. You'll explore:

- Biomechanics and breathing strategies tailored for the perinatal athlete

- Technique review and movement modifications to support performance and healing

- Practical tools for managing pelvic symptoms in high-level exercisers

- Manual therapy techniques specific to this population

Participants should come prepared to move—exercise attire is encouraged for active lab sessions that put knowledge into motion.

Whether you're treating CrossFit athletes, recreational runners, or competitive lifters, this course will give you the confidence to work safely and effectively with perinatal clients committed to staying active.

Prerequisite: Completion of Pelvic Function Level 1 through Herman & Wallace or Pelvic PT 1 through the APTA.

Ready to take your clinical practice to the next level?

Secure your spot in the High Intensity Perinatal Athletics Practicum in Somerset, NJ the weekend of September 27-28th, and empower your work with evidence-based strategies for supporting athleticism in the perinatal journey.

As pelvic rehabilitation therapists, our role has traditionally focused on restoring continence, alleviating pain, and improving quality of life. Yet within athletic populations, pelvic floor dysfunction often presents in unique and nuanced ways—masked by high levels of conditioning, normalized symptoms, or misattributed pain patterns. As the bridge between performance and pelvic health, we are uniquely positioned to address these challenges.

In athletes, the pelvic floor must do more than support visceral structures or maintain continence. It plays an integral role in force transmission, lumbopelvic stability, breathing mechanics, and reflexive motor control. The demands of sport—sprinting, lifting, jumping, cutting—place high, repetitive loads on the core system, often revealing (or creating) dysfunctions in timing, tone, and coordination of the pelvic floor.

The athletic population requires a different lens: one that views the pelvic floor as a functional component of the kinetic chain and not in isolation.

Clinical Presentations: What We Commonly See

- Stress Urinary Incontinence (SUI) in High-Impact Sports: Female athletes, particularly in gymnastics, track, CrossFit, and volleyball, often experience SUI—yet many have strong pelvic floor muscles on MMT. The issue is frequently one of timing, coordination, or excessive tension rather than weakness. Screening for functional incontinence during movement (e.g., jumping or heavy lifting) is essential.

- Hypertonicity and Myofascial Pain: High-performing athletes often exhibit pelvic floor overactivity—either from compensatory stabilization or stress-related holding patterns. These individuals may present with deep hip pain, dyspareunia, tailbone pain, or abdominal discomfort. Common coexisting findings include labral pathology, SIJ dysfunction, and overuse injuries.

- Core Dysfunction and Lumbopelvic Instability: Poor load transfer across the pelvis, impaired breath mechanics, and delayed transversus or multifidus activation often coexist with pelvic floor dyscoordination. This population may present with chronic low back pain, hip impingement, or even sports hernia.

- Postpartum Athletes: Returning to sport postpartum brings unique challenges—diastasis recti, levator avulsion, prolapse, and deconditioning of core synergy. Pressure to return to performance prematurely can exacerbate dysfunction if pelvic rehabilitation is bypassed.

Assessment Considerations for the Athletic Client

In working with athletes, it’s critical to think beyond isolated internal examination and assess whole-system function:

- Breath and Pressure Management: Assess how the client regulates intra-abdominal pressure during dynamic tasks (e.g., lifting, landing, change of direction).

- Pelvic Floor Mobility and Control: Use internal and external assessments to evaluate both overactivity and under-recruitment, including timing during functional movement.

- Core Integration: Test synergistic recruitment of diaphragm, transversus abdominis, multifidus, and pelvic floor during anticipatory and reactive tasks.

- Functional Movement Screens: Incorporate squat mechanics, running gait analysis, lunge variations, and single-leg stability to evaluate force transfer and pelvic control under load.

- Load Testing: Progress assessments to mimic sport-specific demands—e.g., jumping with pelvic floor biofeedback, agility drills with breath cueing.

Treatment Priorities in Pelvic Rehab for Athletes

- Down-Training Before Strengthening: Many athletic clients do not need Kegels—they need to let go. Releasing hypertonic tissues, restoring breath, and retraining pelvic floor length-tension balance is often the starting point. Re-establishing proper sequencing of breath, pelvic floor, and deep core muscles is essential. Use dynamic cuing, load modulation, and real-time feedback (e.g., pressure biofeedback, US imaging) to reinforce neuromotor control.

- Myofascial and Manual Therapy: Trigger point release (levator ani, obturator internus), neural mobilization (pudendal nerve, obturator nerve), and SIJ or hip mobilizations are often necessary for full pelvic system mobility.

- Functional Reintegration: Rehabilitate pelvic floor activation in context—squatting, lifting, running, jumping. Train coordination across planes of motion, not just in supine or side-lying.

- Athlete-Specific Return-to-Play Criteria: Use objective metrics—continence during max effort, pelvic floor coordination under fatigue, breath control under load—to clear clients for return to sport. Consider incorporating pelvic floor testing into movement screens or performance evaluations.

Our Expanding Role

As pelvic rehab therapists, we are more than continence specialists—we are movement specialists. Within sports medicine, we bring a unique capacity to identify root causes of dysfunction that go unseen by traditional orthopedic approaches. Our collaboration with strength coaches, orthopedic PTs, sports MDs, and athletic trainers is critical in shaping a comprehensive, athlete-centered plan.

Pelvic rehabilitation is a performance tool. In the athletic population, our interventions can prevent injuries, improve performance, and support longevity in sport. By approaching the pelvic floor as a dynamic contributor to the kinetic chain, we can elevate the standard of care and advance our profession’s impact in sports medicine.

The Course Options

Athletes and Pelvic Rehabilitation remote course scheduled for July 26-27. In this course, Dr. Dischiavi covers evidence-based, immediately-applicable skills related to pelvic floor rehabilitation for the athlete, including treatment philosophies for the pelvis and pelvic floor, and global considerations of how these structures contribute to human movement. Topics include urinary incontinence, as well as the intricacies of athletic movement and how energy transference throughout the kinetic chain is crucial to the rehabilitation approach, injury prevention, and high performance. This course will also cover biomechanics behind human movement of the lumbopelvic-hip complex, so the participant will be able to prescribe effective and innovative therapeutic exercise programs. The connection of how pelvic rehab influences LE pathologies such as ACL, PFP, and chronic ankle instability will be covered. Although this class has a focus on athletes, these concepts of biomechanics and movement patterning are applicable to all patients in the clinic.

The Runner and Pelvic Health is a one-day, remote course scheduled for July 26, created and instructed by Aparna Rajagopal PT, MHS, WCS, PRPC, and Leeann Taptich DPT, SCS, MTC, CSCS. This course is designed to expand your knowledge of the pelvic floor in running athletes. Through lecture and labs by video and participation, participants will learn what normal and abnormal running mechanics are and how the muscles work simultaneously during running. This course includes advanced assessments to help diagnose the reason for movement dysfunction. All assessments can be easily integrated into a therapist's evaluation skill set. The course is applicable for patients who present with pelvic pain, incontinence, constipation, prolapse, postpartum, and lumbar pain.

Overall prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) ranges from 14.7%-45% within the athletic population (Culleon-Quinn 2022). Additional evidence supports the incidence of PFD within this population (Culleon-Quinn 2022, Rebullido et al 2021, Rodríguez-López et al 2020, Nygaard & Shaw 2016). The athletic population is disproportionately in need of pelvic health services – but much like the general population, many athletes are not aware of the signs and symptoms of PFD, so they may not know to seek care (Bosch-Donate et al, 2024, Cardoso et al, 2018).

In a recent publication in the International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, a group of student and faculty researchers investigated a method of screening collegiate athletes for PFD as a component of the DPT students’ project to promote health in their communities. The intent of the study was to identify the incidence of PFD in collegiate athletes, assess for awareness of PFD, and explore psychosocial factors related to PFD in athletes.

Taking place at the DPT students’ university, student-athletes were recruited from multiple sports teams to participate in a generalized pelvic floor screening in two phases. In the first phase, students completed a demographics section as well as the Cozean Pelvic Dysfunction Screening Tool, a ten-item subjective screening tool. Athletes who scored a “3” or greater on the Cozean Pelvic Dysfunction Screening Tool were then invited to participate in the second phase of screening: a simple, external pelvic floor muscle (PFM) function assessment, performed by the researchers. The researchers chose this score due to the 91% specificity indicating possible PFD in individuals who score 3 or greater on the tool. (Cozean, N 2018)

The researchers performed an external PFM function assessment that included palpation of the coccyx over clothing. This external assessment allowed for improved comfort of the athletes as well as improved efficiency in the performance of the assessment. Coccygeal motion palpation was previously found to be valid when performed by clinicians without formal pelvic health training and was correlated with activation patterns shown via real-time ultrasound, demonstrating 94% sensitivity and 79% specificity in identifying PFM activation patterns (Maher & Iberle, 2020).

For the PFM function assessment, the researchers palpated the tip of the coccyx with the athlete in a seated position as described in the original 2020 study. Participants were then instructed to contract, release, and lengthen their pelvic floor muscles while the student researchers palpated the motion of the coccyx. As described in the validity study, student researchers identified whether or not the coccyx moved anteriorly, posteriorly, or not at all to infer the activity of the PFM. If the student researchers were unsure, the faculty research leader, a Board-Certified Women’s Health Clinical Specialist, and a Certified Pelvic Rehabilitation Practitioner were available on-site to confirm findings.

Once the coccygeal motion palpation was completed, the researchers assigned the athletes into one of three classifications of suspected PFM impairment:

- “normal PFM activity” indicating that the coccyx moved posteriorly with PFM lengthening and anteriorly with PFM contraction

- “increased tone/overactive PFM activity” indicating that the coccyx did not move posteriorly during lengthening, but did move anteriorly with contraction

- “decreased tone/underactive PFM activity” indicating that the coccyx moved posteriorly with lengthening, but did not move anteriorly with contraction

The researchers then shared information with the student athletes pertaining specifically to the suspected PFM impairment identified. Athletes were given information about the PFM, general exercises to consider, as well as resources for finding a trained PT if they desired more formal assessment and interventions.

A quarter (24.5%) of participants scored a “3” or greater on the subjective screening tool, with positive correlations with increased age, self-identified female gender, and increased knowledge of PFD. Swimming athletes were also found to have an increased incidence of positive screening scores as compared to other sports. Following coccygeal motion testing, 54% of the participants were identified as demonstrating “decreased tone/underactive PFM activity” and 39% were identified as demonstrating “increased tone/overactive PFM activity”.

Of the 13 athletes who scored positive on the Cozean Pelvic Dysfunction Screening Tool, 12 also demonstrated objective signs of increased or decreased tone of the PFM during coccygeal motion palpation, (92.3%) reinforcing the Cozean tool’s effectiveness as a simple subjective screening tool for PFD. Additionally, coccygeal motion palpation is a simple, non-invasive, objective screening method that can be taught to clinicians who do not have formal training in pelvic health, allowing for screening to be performed efficiently by all clinicians, and addressing a critical barrier to receiving care.

The results of this study highlight that PFD is often present in physically fit individuals who are competitive athletes. Additionally, 69% of the athlete participants presenting with suspected PFD reported feelings of embarrassment, anxiety, worry, or annoyance with regard to their symptoms, and 62% reported feelings of frustration. 69% of the athletes presenting with suspected PFD reported feeling as though PFD had an effect on athletic performance and 77% reported that PFD had an impact on their personal life. These qualitative findings illustrate that beyond the physical impact of PFD, there is a psychosocial impact as well. By implementing a PFD screening process for athletes, clinicians without formal pelvic health training can help identify athletes who may be experiencing PFD and serve as the initial point of contact to help athletes function better, both on and off the playing field.

By performing screening with a subjective screening tool and an external pelvic floor muscle assessment, the researchers were able to identify athletes demonstrating subjective and objective characteristics of PFD efficiently, while also emphasizing participant comfort. Taking this innovative approach to PFM assessment, it is much more feasible to integrate pelvic floor screening into a standard sports screening performed by a general physical therapist or athletic trainer. Once identified, those professionals can facilitate referral to a physical therapist with pelvic health training for more thorough assessment and treatment. This would allow more athletes with PFD to receive access to care and could have implications for both athletic performance as well as quality of life.

Interested in learning more? Come and see this group speak at APTA’s Combined Sections Meeting in 2025 where they’ll present an educational session about the study and discuss the implementation of this screening process to help ensure that athletes with PFD are identified sooner and receive access to care efficiently.

You can read the published research article, "Screening for Incidence and Effect of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in College-Aged Athletes," here: https://ijspt.org/screening-for-incidence-and-effect-of-pelvic-floor-dysfunction-in-college-aged-athletes/.

AUTHOR BIO

Ashlie Crewe Campitella, PT, DPT, WCS, PRPC

Dr. Ashlie Crewe Campitella earned her Bachelor of Psychology and Doctorate of Physical Therapy at Gannon University prior to beginning her pelvic health training. She is a board-certified women’s health clinical specialist (WCS) and has her certification as a pelvic health practitioner (PRPC) through the Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Dr. Ashlie Crewe Campitella earned her Bachelor of Psychology and Doctorate of Physical Therapy at Gannon University prior to beginning her pelvic health training. She is a board-certified women’s health clinical specialist (WCS) and has her certification as a pelvic health practitioner (PRPC) through the Herman and Wallace Pelvic Rehabilitation Institute.

Ashlie has developed pelvic health continuing education that is comprehensive and inclusive of all genders through the Institute of Advanced Musculoskeletal Treatments, where she is now a lead instructor. She also serves as the Pelvic Health Development Program Coordinator for Upstream Rehabilitation Institute. Additionally, Ashlie is a member of the International Pelvic Pain Society, and the Global Pelvic Health Alliance and serves as an adjunct faculty member at Lebanon Valley College, as well as on the medical advisory board for the Lichen Sclerosus Support Network. She remains in clinical practice in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, treating patients of all ages and genders with pelvic health complaints, with a special focus on implementing a pain neuroscience and trauma-informed approach to pelvic health treatment.

Instructor Sarah Hughes, PT, DPT, OCS, CF - L2 sat down with The Pelvic Rehab Report to answer a couple of questions about treating the Crossfit and weightlifting community. Dr. Hughes earned a BS in exercise science from Gonzaga University and a DPT from the University of Washington.

Sarah's specialties include dance medicine, the CrossFit and weightlifting athlete, and conditions of the hip and pelvis such as femoroacetabular impingement and labral tears. She began coaching other PTs who wanted to start their own practices in 2017 and co-founded Full Draw Consulting with her partner Dr. Kate Blankshain.

Sarah teaches Weightlifting and Functional Fitness Athletes, which s scheduled for August 7th and October 15th of this year.

What are three things you wish you knew when you first started treating the athletic community?

First, I wish that I had had the confidence to treat these athletes the way I saw fit earlier in my career. For a long time, I felt weird treating CrossFit athletes in the clinics I worked in because I felt that my peers were judging me. My colleagues (and many PTs at the time) were wary about the sport and believed it was dangerous for patients. This is a viewpoint I am working to change in our profession.

Secondly, I wish I knew more about how to scale movements in a way that is relevant to the patients and the stimulus they are striving for. For example, if a patient wants to be able to do kipping pull-ups in a workout, giving them banded strict pull-ups as a substitute is not the only option. What about the metabolic conditioning part of the equation? What about looking at the volume and how that is impacting the tissue of concern? This is a big topic that we discuss in my course.

And finally, I wish I knew that being an effective therapist for these athletes does not mean being the top athlete in the gym. In fact, just as with coaching, you do not have to be a great athlete to be a great PT. Again, this is something that I want to change as far too few physical therapists are comfortable treating these or advertising that they treat these athletes because they are not Crossfit athletes (or are not ELITE Crossfit athletes) themselves.

What lesson have you learned in a course, from an instructor, or from a colleague or mentor that has stayed with you?

One important lesson that has stayed with me came from a colleague in Seattle who started her business a year before I started mine. She told me that I needed to listen to my gut when it came to treating these athletes. She reminded me that my experience with CrossFit as a sport, as an athlete, as a coach, and as a PT put me in a position to be an expert on how to help these folks. What I did not need was to allow other physical therapists to sway my thinking and cause me to doubt myself by insisting that we should not be condoning the sport. TRUST YOUR GUT. If you think you are doing what is right for the patients, you are. You might not be right for every patient and that is OK! I am certainly not the right therapist for everyone, but I am indeed right for the community I serve.

Weightlifting and Functional Fitness Athletes - Remote Course

When it comes to Crossfit and Weightlifting, opinions are divided among Physical Therapists and other clinicians. In this half-day, remote continuing education course, instructor Sarah Haran PT, DPT, OCS, CF-L2 looks at the realities and myths related to Crossfit and high-level weight-lifting with the goal of answering “how can we meet these athletes where they are in order to keep them healthy, happy and performing in the sport they love?"

This course reviews the history and style of Crossfit exercise and Weightlifting, as well as examines the role that therapists must play for these athletes. Labs will introduce and practice the movements of Crossfit and Weightlifting, discussing the points of performance for each movement. Practitioners will learn how to speak the language of the athlete and will experience what the movement feels like so that they may help their client to break it down into its components for a sport-specific rehab progression.

The goal of this course is to provide a realistic breakdown of what these athletes are doing on a daily basis and to help remove the stigma that this type of exercise is bad for our patients. It will be important to examine the holes in training for these athletes as well as where we are lacking as therapists in our ability to help these individuals. We will also discuss mindset and cultural issues such as the use of exercise gear (i.e. straps or a weightlifting belt), body image, and the concept of "lifestyle fitness". Finally, we will discuss marketing our practices to these patients.

Course Dates: August 7th and October 15

How does a male sports and orthopedic physical therapist come to teach about pelvic health and wellness? I was fortunate enough to spend ten years in the NHL as the physical therapist and athletic trainer for the Florida Panthers. Ice hockey is one of the sports that has the highest incidence of groin strains among other pelvic related pathologies.1 As a clinician that was responsible for taking care of the world’s best hockey players, I was challenged to understand the interconnected relationships between the lumbopelvic-hip complex very quickly.

In the early years of my career development and the treatment of mostly males with pelvic pathologies, I leaned heavily on pelvic health professionals to help me understand an area of the body I received little training on in school and even less in my clinical care as a sports and orthopedic manual physical therapist. After years of treating hip and pelvic pathologies on my players I became more comfortable in this enigmatic area of the body. A good friend of mine was on faculty with Herman & Wallace and we frequently would communicate and compare notes. She was treating an increasing number of “sports hernias” (now termed athletic pubalgia or core muscle injury) and was relying on me to help her understand this injury and how to treat it. In turn, she helped me understand what went on in the pelvic health profession and what those therapists were trained to treat and how they went about it.

In the early years of my career development and the treatment of mostly males with pelvic pathologies, I leaned heavily on pelvic health professionals to help me understand an area of the body I received little training on in school and even less in my clinical care as a sports and orthopedic manual physical therapist. After years of treating hip and pelvic pathologies on my players I became more comfortable in this enigmatic area of the body. A good friend of mine was on faculty with Herman & Wallace and we frequently would communicate and compare notes. She was treating an increasing number of “sports hernias” (now termed athletic pubalgia or core muscle injury) and was relying on me to help her understand this injury and how to treat it. In turn, she helped me understand what went on in the pelvic health profession and what those therapists were trained to treat and how they went about it.

This collaboration eventually led to me joining Herman & Wallace and offering a sports and orthopedic perspective to pelvic floor consideration. I have attended Herman & Wallace’s Pelvic Floor courses to fully understand the training that a pelvic health therapist undergoes. Admittedly, I do not perform internal work because I have found a niche helping clinicians such as myself who understand that the pelvic floor is a key variable in human movement and we need to understand it at a much higher level than what we are exposed to in school, but don’t have the career trajectory of becoming an internal practitioner of the pelvic floor.

I have designed the Athletes and Pelvic Rehabilitation course to reach both the sports and orthopedic clinician as well as the pelvic health practitioner who might be a veteran of pelvic floor education and treatment. Both groups will leave this course with additional tools for their clinical tool box in the realms of manual therapy and exercise.2 Here are some of the objectives for the course:

- Provide clinicians that do not perform internal work a better and more complete understanding of how the pelvic floor integrates into human movement, particularly higher-level activities such as running, lifting and all types of sporting movements.

- Provide both the experienced and pelvic floor early learner with a comprehensive paradigm of exercise theory, development and progressions as well as how to provide non-internal manual therapy to influence the performance of the pelvic floor.

- Provide strategies for clinicians to determine when your patient would be better served with a referral to a pelvic health practitioner and what the current evidence is to support your decision.

- Create innovative and engaging therapeutic exercise programs (home exercise programs too!) for your patients directed at the pelvis with specific attention to upright and functional positioning.

What do people who have attended courses with Dr. Dischiavi have to say? Janna wrote the following email to Herman & Wallace about Steve's Course:

"Good morning. I wanted to make sure that you knew what a fantastic clinician you have to join your team in Steve Dischiavi. I am a practicing OB and orthopedic therapist and felt this course was fantastic! Usually the main goal is to come away with a couple of clinical "pearls." I felt as though I came away with a full days worth of "pearls." I really liked that the course was not totally pelvic floor based, however was totally relevant to the women's health population, but it will also apply to the majority of my current patient population as well. Thank you for the opportunity to learn from Steve!"

1. Orchard JW. Men at higher risk of groin injuries in elite team sports: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(12):798-802.

2. Tuttle L. The Role of the Obturator Internus Muscle in Pelvic Floor Function. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2016;40(1):15-19.

When It Comes to Bone Building Activities for Osteoporosis, there’s Weight Bearing and then there’s Weight Bearing!

Ask just about anyone on the street what one should do for osteoporosis and the typical answer is- weight bearing exercises. And they would be partially right. Weight bearing, or loading activities have been shown to increase bone density.1 But that’s not the whole story.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

Regarding weight bearing exercises, the million-dollar question is, “How much weight bearing is enough to stimulate bone growth and how much is too much to compromise bone at risk for a fracture? We know that there are incidents of individuals fracturing from just their own body weight upon standing. Recently patients have been asking about heel drops and stomping, and whether they should do them. One size does not fit all.

An alternative is to focus on “odd impact” loading. A study by Nikander et al 2 targeted female athletes in a variety of sports classified by the type of loading they apparently produce at the hip region; that is, high-impact loading (volleyball, hurdling), odd-impact loading (squash-playing, soccer, speed-skating, step aerobics), high magnitude loading (weightlifting), low-impact loading (orienteering, cross-country skiing), and non-impact loading (swimming, cycling). The results showed high-impact and odd-impact loading sports were associated with the highest bone mineral density.

Morques et al, in Exercise Effects on Bone Mineral Density in Older Adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, found that odd impact has potential for preserving bone mass density as does high impact in older women. Activities such as side stepping, figure eights, backward walking, and walking in square patterns help “surprise the bones” due to different angles of muscular pull on the hip. The benefit, according to Nikander, is that we can get the same osteogenic benefits with less force; moderate versus high impact. This type of bone training would offer a feasible basis for targeted exercise-based prevention of hip fragility. I tell my osteoporosis patients that if they walk or run the same route, the same distance, and the same speed that they are not maximizing the osteogenic benefits of weight bearing. Providing variety to the bones creates increased bone mass in the femoral neck and lumbar spine.4

Dancing is another great activity which combines forward, side, backward, and diagonal motions to movement. In addition, it adds music to make the “weight bearing exercises” more fun. Due to balance and fall risk many senior exercise classes offer Chair exercise to music. Unfortunately sitting is the most compressive position for the spine and is particularly problematic with osteoporosis patients. Also the hips do not get any weight bearing benefit. Whenever safely possible, have patients stand; you can position two kitchen chairs on either side, much like parallel bars, to hold on to while they “dance.”

Providing creativity in weight bearing activities using odd impact allows not only for fun and stimulation; it also offers more “bang for the buck!”

- Mosekilde L. Age-related changes in bone mass, structure, and strength--effects of loading. Z Rheumatol (2000); 59 Suppl 1:1-9.

- Nikander et al. Targeted exercises against hip fragility. Osteoporosis International (2009)

- Marques et al. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in older adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Epub 2011 Sep 16

- Weidauer L. et al. Odd-impact loading results in increased cortical area and moments of inertia in collegiate athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol (2014)

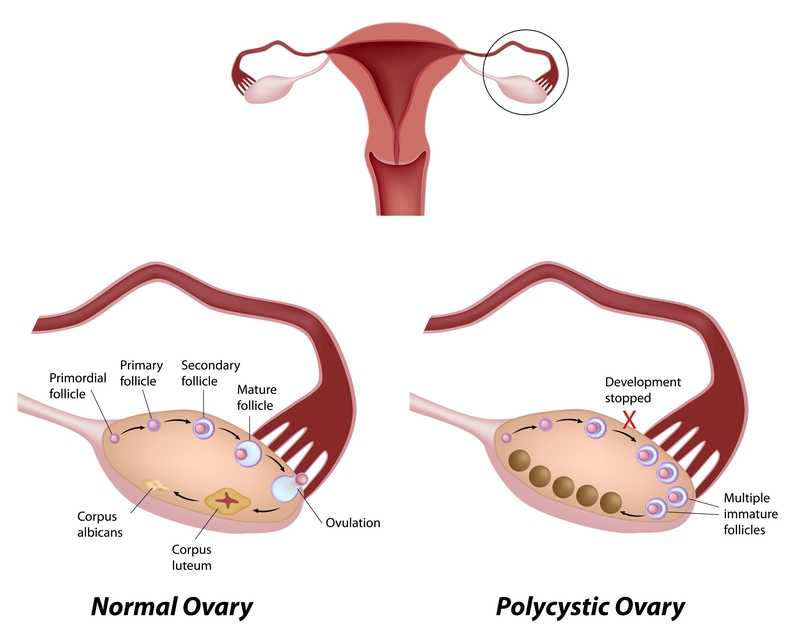

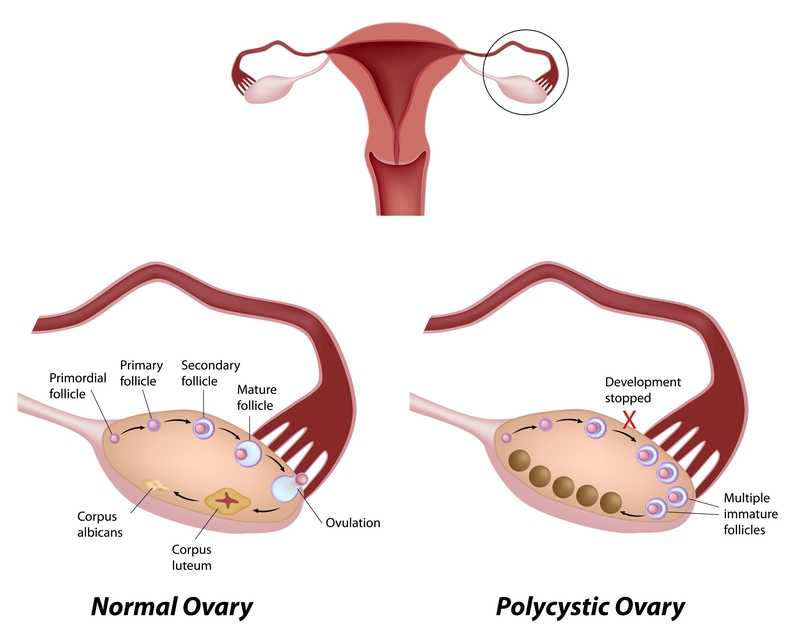

Few patients discuss polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in orthopedic manual therapy, but one lady left a lasting impression. She was adopted and did not know her family’s medical history or her genetics. At 18, she had a baby as a result of rape. At 34, she was married and diagnosed with POCS. She struggled with infertility, anxiety, obesity, and hypertension. Although I saw her for cervicalgia, the exercise aspect of her therapy had potential to impact her overall well-being and possibly improve her PCOS symptoms.

Pericleous & Stephanides (2018) reviewed 10 studies that considered the effects of resistance training on PCOS symptoms. Some of these symptoms include the absence of or a significant decrease in ovulation and menstruation, which can lead to infertility; obesity, which in turn can affect cardiovascular health and increase the risk of diabetes, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome; and, mental health problems. Research has shown resistance training benefits include lowering body fat, improving insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, and increasing insulin sensitivity in type II diabetes. Although it has been documented that obesity and insulin resistance can exacerbate PCOS symptoms, resistance training is not a common recommendation in healthcare settings for patients with PCOS . Studies have shown diet and exercise are essential to improve cardiac and respiratory health and body makeup in patients with PCOS, as the combination improves the Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), ovulation, testosterone levels, and weight loss. One systematic review found that weight loss can improve PCOS symptoms without consideration of diet; however, most other studies find intake of various macronutrients (protein, fat, carbohydrates) may lead to different results, and the effects of resistance training can only be optimized with appropriate dietary changes. These authors concluded caloric consumption and macronutrient habits must be considered in conjunction with resistance training to determine the greatest impact on improving PCOS symptoms.

Pericleous & Stephanides (2018) reviewed 10 studies that considered the effects of resistance training on PCOS symptoms. Some of these symptoms include the absence of or a significant decrease in ovulation and menstruation, which can lead to infertility; obesity, which in turn can affect cardiovascular health and increase the risk of diabetes, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome; and, mental health problems. Research has shown resistance training benefits include lowering body fat, improving insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, and increasing insulin sensitivity in type II diabetes. Although it has been documented that obesity and insulin resistance can exacerbate PCOS symptoms, resistance training is not a common recommendation in healthcare settings for patients with PCOS . Studies have shown diet and exercise are essential to improve cardiac and respiratory health and body makeup in patients with PCOS, as the combination improves the Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), ovulation, testosterone levels, and weight loss. One systematic review found that weight loss can improve PCOS symptoms without consideration of diet; however, most other studies find intake of various macronutrients (protein, fat, carbohydrates) may lead to different results, and the effects of resistance training can only be optimized with appropriate dietary changes. These authors concluded caloric consumption and macronutrient habits must be considered in conjunction with resistance training to determine the greatest impact on improving PCOS symptoms.

Benham et al., (2018) also performed a recent systematic review to assess the role exercise can have on PCOS. Fourteen trials involving 617 females of reproductive age with PCOS evaluated the effect of exercise training on reproductive outcomes. The data published did not allow the authors to quantitatively assess the impact of exercise of reproductive in PCOS patients; however, their semi-quantitative analysis allowed them to propose exercise may improve regularity of menstruation, the rate of ovulation, and pregnancy rates in these women. Via meta-analysis, secondary outcomes of body measurement and metabolic parameters significantly improved after women with PCOS underwent exercise training; however, symptoms such as acne and hirsutism (excessive, abnormal body hair growth) were not changed with exercise. The authors concluded exercise does improve the metabolic health (ie, insulin resistance) in women with PCOS, but evidence is insufficient to measure the exact impact on the function of the reproductive system.

Increasing our knowledge about comorbidities such as PCOS, regardless of our practice setting, can help us provide better education to the patients we treat. Perhaps exercise compliance can increase when patients are told multiple long-term benefits, not just immediate symptom relief. More often than not, a patient’s 4-6 week interaction with us could motivate and promote healthy lifestyle changes.

Pericleous, P., & Stephanides, S. (2018). Can resistance training improve the symptoms of polycystic ovary syndrome? BMJ Open Sport — Exercise Medicine, 4(1), e000372. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000372

Benham, J. L., Yamamoto, J. M., Friedenreich, C. M., Rabi, D. M. and Sigal, R. J. (2018), Role of exercise training in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Obes, 8: 275-284. doi:10.1111/cob.12258

Suggested newly published resource for readers…

Teede, H. J., Misso, M. L., Costello, M. F., Dokras, A., Laven, J., Moran, L., … Yildiz, B. O. (2018). Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 33(9), 1602–1618. http://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dey256

A couple of years ago, I wrote a blog about an interesting article by Hides and Stanton that related size and strength of the multifidus to the risk for lower extremity injury in Australian professional football players.

Now some of the same researchers are looking above. A prospective cohort study has recently been published that examined factors and their effects on concussions. Physical measurements of risk factors were taken in pre-season among Australian football players. These measurements included balance, vestibular function, and spinal control. To measure these outcomes the following tests were included: for balance the amount of sway across six test conditions were performed; vestibular function was tested with assessments of ocular-motor and vestibular ocular reflex; and for spinal control cervical joint position error, multifidus size, and contraction ability was tested. The objective measure was concussion injury obtained during the season diagnosed by the medical staff.

Now some of the same researchers are looking above. A prospective cohort study has recently been published that examined factors and their effects on concussions. Physical measurements of risk factors were taken in pre-season among Australian football players. These measurements included balance, vestibular function, and spinal control. To measure these outcomes the following tests were included: for balance the amount of sway across six test conditions were performed; vestibular function was tested with assessments of ocular-motor and vestibular ocular reflex; and for spinal control cervical joint position error, multifidus size, and contraction ability was tested. The objective measure was concussion injury obtained during the season diagnosed by the medical staff.

The findings were so interesting! Age, height, weight, and number of years playing football were not associated with concussion. Cross-sectional area of the multifidus at L5 was 10% smaller in players who went on to sustain a concussion compared to players that did not receive a concussion. There were no significant differences observed between the players that received concussion and those who did not with respect to the other physical measures that were obtained.

With all the recent evidence about the harmful effects of concussions amongst our athletes, I find this information amazing and am excited to see where the researchers take this in the future. The next question for the physical therapist is how do we train the multifidus? The multifidus can be difficult to retrain in some individuals. It is a hard muscle for some patients to learn to recruit. Biofeedback using ultrasound imaging can make this daunting task easier for many patients. With the cost of ultrasound units coming down, it is also a very reasonable tool for clinics to look at investing in.

Join me to learn more about the multifidus and how to use ultrasound imaging in the retraining process. Future course offerings include August in New Jersey, and November in San Diego. I look forward to seeing you there!

Hides, Stanton. Can motor control training lower the risk of injury for professional football players? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014; 46(4): 762-8.

Leung, Hides, Franettovich Smith, et al. Spinal control is related to concussion in professional footballers. Brit J of Sports Med. 2017; 51(11).

In the dim and distant past, before I specialised in pelvic rehab, I worked in sports medicine and orthopaedics. Like all good therapists, I was taught to screen for cauda equina issues – I would ask a blanket question ‘Any problems with your bladder or bowel?’ whilst silently praying ‘Please say no so we don’t have to talk about it…’ Fast forward twenty years and now, of course, it is pretty much all I talk about!

But what about the crossover between sports medicine and pelvic health? The issues around continence and prolapse in athletes is finally starting to get the attention it deserves – we know female athletes, even elite nulliparous athletes, have pelvic floor dysfunction, particularly stress incontinence. We are also starting to recognise the issues postnatal athletes face in returning to their previous level of sporting participation. We have seen the changing terminology around the Female Athlete Triad, as it morphed to the Female Athlete Tetrad and eventually to RED S (Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome) and an overdue acknowledgement by the IOC that these issues affected male athletes too. All of these issues are extensively covered in my Athlete & The Pelvic Floor’ course, which is taking place twice in 2018.

But what about pelvic pain in athletes?

How can we ensure that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is on the radar for a differential diagnosis, or perhaps a concomitant factor, when it comes to athletes presenting with hip, pelvis or groin pain? Gluteal injuries, proximal hamstring injuries, and pelvic floor disorders have been reported in the literature among runners: with some suggestions that hip, pelvis, and/or groin injuries occur in 3.3% to 11.5% of long distance runners.

How can we ensure that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is on the radar for a differential diagnosis, or perhaps a concomitant factor, when it comes to athletes presenting with hip, pelvis or groin pain? Gluteal injuries, proximal hamstring injuries, and pelvic floor disorders have been reported in the literature among runners: with some suggestions that hip, pelvis, and/or groin injuries occur in 3.3% to 11.5% of long distance runners.

In Podschun’s 2013 paper ‘Differential diagnosis of deep gluteal pain in a female runner with pelvic involvement: a case report’, the author explored the case of a 45-year-old female distance runner who was referred to physical therapy for proximal hamstring pain that had been present for several months. This pain limited her ability to tolerate sitting and caused her to cease running. Examination of the patient's lumbar spine, pelvis, and lower extremity led to the initial differential diagnosis of hamstring syndrome and ischiogluteal bursitis. The patient's primary symptoms improved during the initial four visits, which focused on education, pain management, trunk stabilization and gluteus maximus strengthening, however pelvic pain persisted. Further examination led to a secondary diagnosis of pelvic floor hypertonic disorder. Interventions to address the pelvic floor led to resolution of symptoms and return to running.

‘This case suggests the interdependence of lumbopelvic and lower extremity kinematics in complaints of hamstring, posterior thigh and pelvic floor disorders. This case highlights the importance of a thorough examination as well as the need to consider a regional interdependence of the pelvic floor and lower quarter when treating individuals with proximal hamstring pain.’ (Podschun 2013)

Many athletes who present with proximal hamstring tendinopathy or recurrent hamstring strains, display poor ability to control their pelvic position throughout the performance of functional movements for their sport: along with a graded eccentric programme, Sherry & Best concluded ‘…A rehabilitation program consisting of progressive agility and trunk stabilization exercises is more effective than a program emphasizing isolated hamstring stretching and strengthening in promoting return to sports and preventing injury recurrence in athletes suffering an acute hamstring strain’

If you are interested in learning more about how pelvic floor dysfunction affects both male and female athletes, including broadening your differential diagnosis skills and expanding your external treatment strategy toolbox, then consider coming along to my course ‘The Athlete and the Pelvic Floor’ in Chicago this June or Columbus, OH in October.

The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), Mountjoy et al 2014: http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/48/7/491

‘DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DEEP GLUTEAL PAIN IN A FEMALE RUNNER WITH PELVIC INVOLVEMENT: A CASE REPORT’ Podschun A et al Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Aug; 8(4): 462–471. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3812833/

‘A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains’ Sherry MA, Best TM J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004 Mar;34(3):116-25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15089024

One of my greatest nemeses when I was racing at 30 years of age was a woman in her 50’s. Although I hated losing to her, I was always inspired by her speed at her age. She motivated me to continue training hard, realizing my fastest days could be yet to come. As I now race in the “master’s” category in my 40’s, I still find myself crossing the line behind an older competitor occasionally. Research shows I should take heart and keep in step with females who continue to move their bodies beyond menopause.

Mazurek et al., (2017) studied how organized physical activity among post-menopausal women could reduce cardiovascular risk. The study included 35 sedentary women aged 64.7 ± 7.7 years who had no serious health issues. They all participated in the Active Leisure Time Programme (ALTP) 3 times per day for 40–75 minute sessions for 2 weeks, including 39 physical activities. Exercise intensity stayed within 40–60% of maximal HR, and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) on the Borg scale stayed between 8 and 15 points. This exercise training was followed by 3 months of the Prevent Falls in the Elderly Programme (PFEP), which is a general fitness exercise program to prevent falls in the elderly. Health status was measured at baseline, 2 weeks into the program, and after 3 months. The results showed significant reductions in central obesity, which increased the exercise and aerobic capacity of the subjects and improved lipid profiles. A significant reduction also occurred in the absolute 10-year risk of death from cardiac complications. The authors concluded these exercise programs could be effective in preventing primary and secondary cardiovascular disease in the >55 years old female population.

Mazurek et al., (2017) studied how organized physical activity among post-menopausal women could reduce cardiovascular risk. The study included 35 sedentary women aged 64.7 ± 7.7 years who had no serious health issues. They all participated in the Active Leisure Time Programme (ALTP) 3 times per day for 40–75 minute sessions for 2 weeks, including 39 physical activities. Exercise intensity stayed within 40–60% of maximal HR, and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) on the Borg scale stayed between 8 and 15 points. This exercise training was followed by 3 months of the Prevent Falls in the Elderly Programme (PFEP), which is a general fitness exercise program to prevent falls in the elderly. Health status was measured at baseline, 2 weeks into the program, and after 3 months. The results showed significant reductions in central obesity, which increased the exercise and aerobic capacity of the subjects and improved lipid profiles. A significant reduction also occurred in the absolute 10-year risk of death from cardiac complications. The authors concluded these exercise programs could be effective in preventing primary and secondary cardiovascular disease in the >55 years old female population.

Nyberg et al., (2016) took a physiological look at exercise training on the vascular function of pre- and postmenopausal women, studying the prostanoid system. Prostanoids are vasoconstrictors, and prostacyclins are vasodilators. The loss of estrogen in menopause affects the ability of the vasodilators to function properly or even be produced, thus contributing to vascular decline. The authors checked the vasodilator response to an intra-arterial fusion of a prostacyclin analog epoprostenol as well as acetylocholine in 20 premenopausal and 16 early postmenopausal women before and after a 12-week exercise program. Pre-exercise, the postmenopausal women had a reduced vasodilator response. The women also received infusion of ketorolac (an inhibitor of cyclooxygenase) along with acetylcholine, creating a vasoconstriction effect, and the vascular response was reduced in both groups. The infusions and analyses were performed again after 12 weeks of exercise training, and the exercise training increased the vasodilator response to epoprostenol and acetylcholine in the postmenopausal group. The reduced vasodilator response to epoprostenol prior to exercise in early postmenopausal women suggests hormonal changes affect the capacity of prostacyclin signaling; however, the prostanoid balance for pre and postmenopausal women was unchanged. Ultimately, the study showed exercise training can still have a positive effect on the vascularity of newly postmenopausal women.

There are randomized controlled clinical trials and scientific evidence supporting the importance to keep moving as women (and men) age. Menopause should not be a self-proclaimed pause from activity in life. Not everyone has to become a competitive athlete to preserve cardiac and vascular integrity as we age, but we need to engage in some physical activity to keep our systems running for years to come.

Those interested in learning more about menopause rehabilitation considerations should consider attending Menopause Rehabilitation and Symptom Management.

Mazurek, K., Żmijewski, P., Kozdroń, E., Fojt, A., Czajkowska, A., Szczypiorski, P., Tomasz Mazurek, T. (2017). Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Sedentary Postmenopausal Women During Organised Physical Activity. Kardiologia Polska. 75, 5: 476–485. http://doi:10.5603/KP.a2017.0035

Nyberg, M., Egelund, J., Mandrup, C., Nielsen, M., Mogensen, A., Stallknecht, B., Bangsbo, J., Hellsten, Y. (2016). Early Postmenopausal Phase Is Associated With Reduced Prostacyclin-Induced Vasodilation That Is Reversed by Exercise Training: The Copenhagen Women Study. Hypertension. 68:1011-1020. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07866